Column: For the second time in days, the Supreme Court helped make another Trump presidency possible

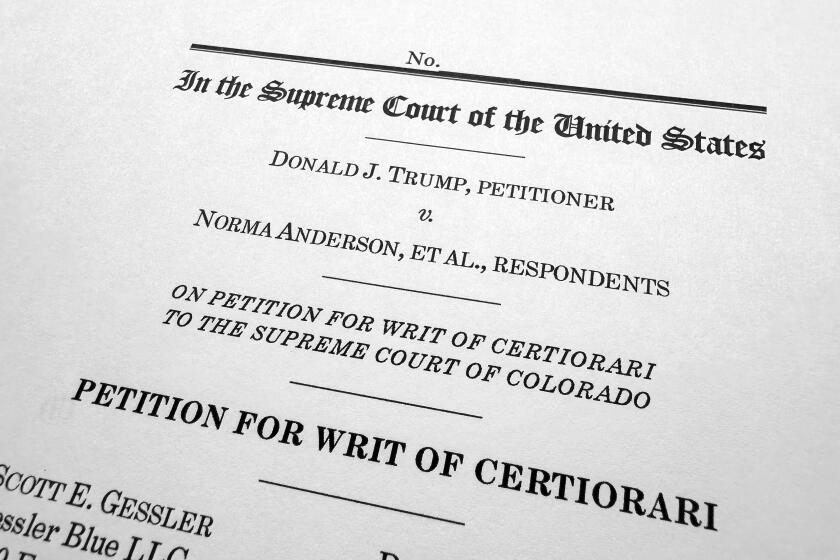

The Supreme Court held Monday that a single state such as Colorado can’t prohibit Donald Trump from running for president as an insurrectionist under the 14th Amendment. It was the second time in less than a week that the court provided a crucial boost to the former president’s campaign to return to the White House.

The court’s strong inclination to restore Trump to the ballot was clear from the oral argument in the case last month, and indeed the justices reversed the Colorado Supreme Court unanimously. The “per curiam,” or “by the court,” opinion further emphasized that the court was speaking with a single voice.

But the justices were far from united on the rationale for reversal. There was a clear 5-4 split with two concurrences, one by the liberal justices — Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson — and the other by Justice Amy Coney Barrett.

The justices will hear arguments in the federal Jan. 6 case, delaying the ex-president’s prosecution for months as his campaign to return to the White House proceeds.

The narrow, right-wing majority within the unanimous decision held that congressional legislation is needed to enforce Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which prohibits elected officials who engage in insurrection from holding office again. This clearly restricts the amendment’s force going forward.

All four of the concurring justices parted from requiring a federal law to enforce Section 3. For them, it was sufficient that the Colorado decision would impose an inconsistent and intolerable patchwork in which a major presidential candidate appeared on the ballot in some states but not in others. As the court wrote, “Nothing in the Constitution requires that we endure such chaos.”

The opinion signed by the three Democratic-appointed justices, though styled as a concurrence, was fairly sharp in its differences with the majority. Most pointedly, they quoted Justice Stephen G. Breyer’s dissent in Bush vs. Gore, the 2000 opinion that remains a bête noire for liberals: “What it does today, the Court should have left undone.”

The former president’s disqualification for insurrection under the 14th Amendment in Colorado threatens to make a mess the justices will likely try to avoid.

Barrett similarly felt that her five fellow conservatives had overreached. But she sounded a conciliatory note, writing that “this is not the time to amplify disagreement with stridency.”

So although the court was able to come together as to the result, surely a priority for Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., its political divisions were evident just beneath the surface. It was no kumbaya moment.

In cases of this magnitude and political stakes, the court is better off when it’s unanimous or nearly so. Kagan and Jackson, who seemed to be leaning toward reversal at oral argument, and even Sotomayor, whose inclination was less clear, thereby stepped up in the service of the court’s institutional interest. Notwithstanding their fundamental differences with the majority, their concurrences permitted the court to conclude with a feel-good paragraph noting that “All nine Members of the Court agree with that result.” They were good soldiers and team players, which may engender goodwill with Roberts going forward.

Of course, with the rock-ribbed conservatives to the chief justice’s right, there may be scant prospect of similar goodwill. The court’s right has been in lockstep on ideologically divisive matters, and there’s no reason to expect that to change.

Indeed, after last week’s decision to review the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals’ rejection of Trump’s claim of immunity from prosecution for Jan. 6, today’s decisive ruling is a second substantial victory for the president who appointed three of the justices.

Some observers speculated that the justices would view the two Trump cases, on immunity and the 14th Amendment, as a pair that they would split. Ruling for Trump on the Colorado case and against him on the Jan. 6 prosecution would communicate a sort of neutrality.

It’s difficult to see it that way now, though. Not that the court will hold that Trump is immune from the charges growing out of his perfidious attempts to overturn the results of the 2020 eleciton. The best he can hope for is a remand to the trial court and eventual loss on the merits of his immunity claim.

But the court last week gave Trump the invaluable gift of time, suspending the proceedings in Judge Tanya Chutkan’s U.S. District Court for at least several months, leaving serious doubt as to whether the case can be tried before the election.

If the polls are to be believed, a criminal conviction would likely persuade a significant number of voters to abandon Trump. That means the court’s decision to enter the fray and delay the case — when it could have let the D.C. Circuit’s thorough, bipartisan opinion stand — is probably the most important assist it could have given to Trump’s campaign.

Moreover, while the court acted with some dispatch in the immunity case, it was nowhere near as quick as in other exigent cases. That includes the one it decided Monday, rushing to clarify the electoral landscape just in time for Colorado and other states to vote on Super Tuesday.

There’s plenty of room for debate as to why the court acted as it did in each case. But there’s no doubt about the impact. Should the country awaken on Nov. 6 to the horrifying prospect of a second Trump presidency, history will record that the Supreme Court played a critical role.

Harry Litman is the host of the “Talking Feds” podcast. @harrylitman

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.