Editorial: Another court decision weakens the Voting Rights Act. Will the Supreme Court right this wrong?

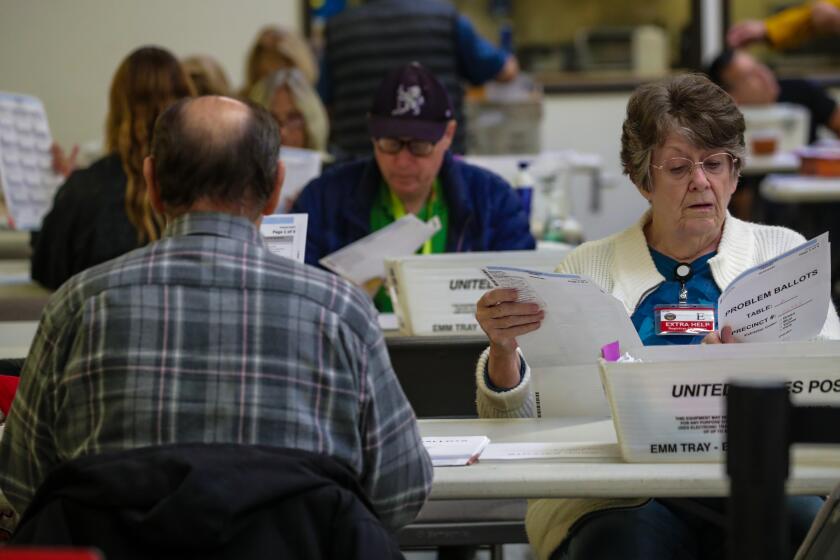

A federal appeals court panel handed down a decision last week that would hobble enforcement of the Voting Rights Act by holding that only the U.S. attorney general, not aggrieved citizens, can file lawsuits to enforce one of the landmark civil rights law’s key protections. The Supreme Court, which has a checkered history when it comes to protecting voting rights, must overrule this radical decision if it is appealed, which is likely.

In a dispute arising from challenges to a legislative redistricting plan in Arkansas, the U.S. 8th Circuit panel ruled that, because the text of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act doesn’t authorize lawsuits by private individuals, such suits may not proceed.

Senate Democrats must do everything they can to pass the voting rights reforms while they still have the chance

Writing for the 2-1 majority, Judge David R. Stras said that “silence is not golden for the plaintiffs.” Never mind that, as a dissent by Chief Judge Lavenski Smith pointed out, federal courts across the country, including the Supreme Court, have considered numerous Section 2 cases brought by private plaintiffs. Congress also made clear in committee reports that it envisioned private lawsuits, a fact shrugged off by the majority opinion with the dismissive comment that there “are many reasons to doubt legislative history as an interpretive tool.” (Earlier this month, another federal appeals court, the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, concluded that private parties could sue under Section 2.)

The Voting Rights Act, originally signed into law in 1965, initially was seen as protection against blatant attempts by states, mostly in the South, to prevent Black voters from participating in elections, despite the guarantee in the 15th Amendment that the right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

New research has uncovered a troubling exodus of local election officials — those on the front lines fighting to preserve and protect our democracy. Lawmakers need to act.

The law requires that jurisdictions with a history of voting discrimination to “pre-clear” changes in election procedures with a federal court or the U.S. attorney general — a provision that was gutted by a disastrous 2013 decision in Shelby County vs. Holder. But it also includes a provision, Section 2, that applies nationwide and prohibits voting practices or procedures that discriminate on the basis of race, color or membership in language minority groups.

As the Voting Rights Act has evolved and been amended, it addresses not only restrictions on an individual’s right to vote but on official action — such as redistricting maps — that give minority groups “less opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.” That development is entirely appropriate. In an ideal world, the racial makeup of a legislative or congressional district might be irrelevant. But in the real world of persistent racism, the Voting Rights Act provides a check on even subtle attempts to weaken the political power of nonwhite voters.

Today’s disenfranchisement efforts show less raw violence than in the Klan era, but more sophisticated means of voter suppression.

The law is not much of a protection, however, if it can’t be enforced through litigation. Richard L. Hasen, a voting rights expert at UCLA Law School, warned that it was “hard to overstate how important and detrimental this decision would be if allowed to stand: the vast majority of claims to enforce Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act are brought by private plaintiffs, not the Department of Justice with limited resources.”

Although it hasn’t repented of its reckless decision in Shelby County vs. Holder, the Supreme Court sometimes has ruled in ways that support the ambitious objectives of the Voting Rights Act. In June, the court by a 5-4 vote ruled in a case involving citizen plaintiffs that Alabama likely had diluted the power of Black voters in fashioning a congressional map. The majority opinion was written by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., the author of the Shelby County opinion. Roberts and the other justices should similarly bolster voting rights by reversing the 8th Circuit panel’s misreading of the law if and when it comes before them.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.