Column: What kind of terrible parent pays their child to get an A? (Well, me)

Is it OK to pay a child to do well in school?

I’m currently grappling with this question. Five years ago, my then-8-year-old niece moved in with me. Overnight, I became a single “mom” to a wonderful, if emotionally fragile, third-grader.

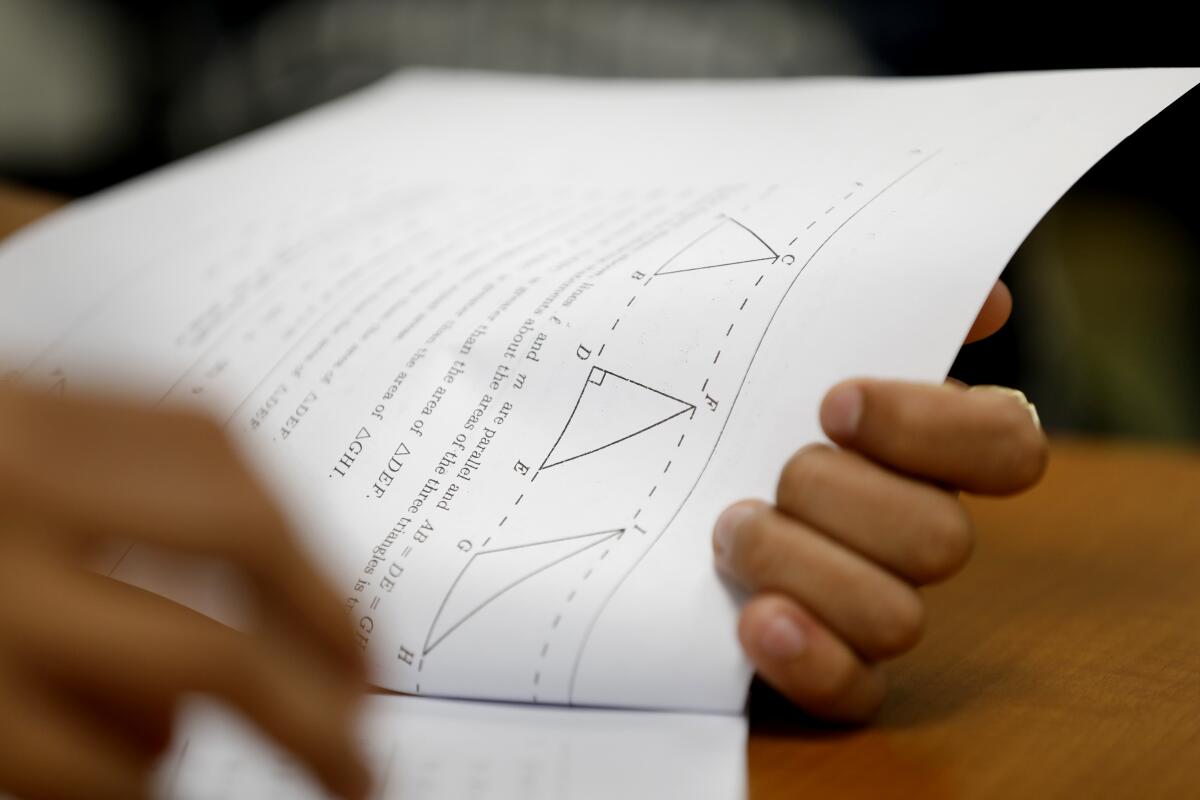

She had been through a lot — four schools in two years — and so I wasn’t sure what to expect from her academically. But she thrived in our local elementary school. And now she’s finding her passions as an eighth-grade middle schooler in mostly honors classes. With the exception of math. A struggle I understand.

In elementary and middle school, I did well enough in other classes, but I was a solid C math student. In 10th grade, however, something just clicked. At Cleveland High School, in Reseda, I had a fabulous geometry teacher. His name was Mr. Maung. I have no idea what became of him, but he was one of the best teachers I ever had. I earned an A in his class, and I never took another math course.

When my niece was in sixth grade and began struggling with numbers, we signed up for one of those costly math tutoring programs. She went for an hour after school a couple of times a week. After nearly a year with no change in her grades, I discovered that the place wasn’t really working with her on her school curriculum, which I’d assumed was the whole point. They had their own methodology for teaching the subject, and if they had time at the end of her session, they might help her with her homework. Ugh.

The next year, in seventh grade, she again struggled with low grades in math. I conferred frequently with her teacher. She did after-school “interventions” in the library. Things didn’t improve. Well, I thought, she has lots of other skills and talents.

Relax, parents. Swearing is not only developmentally appropriate, it helps empower children

This year, however, when she floundered on her first few math tests, I became alarmed. High school is just around the corner, and I suspected she was capable of doing well in math class but just wasn’t that interested. And maybe she was even a little invested in acting like she didn’t care.

Two weeks ago, I had a brainstorm: money. Couldn’t hurt, right? So I texted her: “I will give you 20 bucks if you get a B. [Smiley face emoji]”

“OMG,” she replied. “40 for an A!”

“Done!”

I admit: As a parent, this was not my finest hour.

Also, I was pretty sure she’d never get an A.

Billions of dollars in state and federal pandemic relief have yet to pay academic dividends with K-12 students, although officials remain optimistic.

Amy McCready, a parenting coach who founded the online education site Positive Parenting Solutions, did not judge me when I told her about my deal with my niece. She disapproved but in the nicest possible way.

“Parents will say, ‘I get paid to work,’ and my kid’s job is school, so why not pay them?’ But there are some unintended consequences to that,” said the Raleigh, N.C.-based McCready, who wrote the 2015 book “The Me, Me, Me Epidemic: A Step-by-Step Guide to Raising Capable, Grateful Kids in an Over-Entitled World.”

The first problem, supported by lots of research, is that external rewards tend to decrease intrinsic motivation — you know, the feeling that good grades and mastery of a subject are their own reward.

Something more concrete, said McCready, “can provide a quick hit, but we need to think about the long-term goal — the love of learning, intellectual curiosity, an interest in math.”

I want my niece to love reading as much as I do. She doesn’t. Arguments ensue. The experts’ advice? Chill out — kids read differently these days.

She pointed me to the book “Punished by Rewards: The Trouble With Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A’s, Praise, and Other Bribes” by the prolific education writer Alfie Kohn, first published in 1993, now revised for its 25th anniversary. Kohn addresses the failures of “behaviorism” — as propounded by the psychologist B.F. Skinner — to manipulate people into changing their behavior by rewarding them, which he calls “do this and you’ll get that.”

“To take what people want or need and offer it on a contingent basis in order to control how they act,” he writes, “this is where the trouble lies.”

As McCready told me, paying for grades is ultimately not sustainable. “The reward loses its luster,” she said. “The problem is you have to keep upping the ante.”

The practice can also discourage children who really are struggling. “What if they are working their hardest and are not getting the A or B,” she said. “They should be rewarded for working their tail off.” (And by “rewarded,” she means they should be celebrated. “I distinguish between rewards and celebrations. A reward is contingent, versus, ‘Wow, you have been putting so much time into your math, let’s go celebrate that.’”)

A reparations task force puts a number to the economic suffering of Black Californians. That’s a start.

But that’s my issue with my niece. I don’t think she has been working her hardest, and I believe she is capable of doing better.

I just needed to figure out how to motivate her. Hence, the bribe, which coincided with her recent acquisition of an iPhone. (We’d had a pact: She would wait until eighth grade for a phone with apps and internet access.) Once she discovered Apple Pay, the app that lets anyone transfer money to your account, she became transfixed by the balance in her account.

“Wow,” she said when she had accumulated $52. “I’m getting rich!”

At this point, you are probably wondering how she did on that math test. I am thrilled — more or less — to report that she got her first A. I dutifully added $40 to her Apple Pay coffers.

And now I am in the difficult position of having to decide whether to continue in this race to the behaviorism bottom or to raise my standards in the service of making her a better student and all-around human being.

I’m thinking, I’m thinking.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.