Column: Can nonviolent activism survive America’s outrage machine?

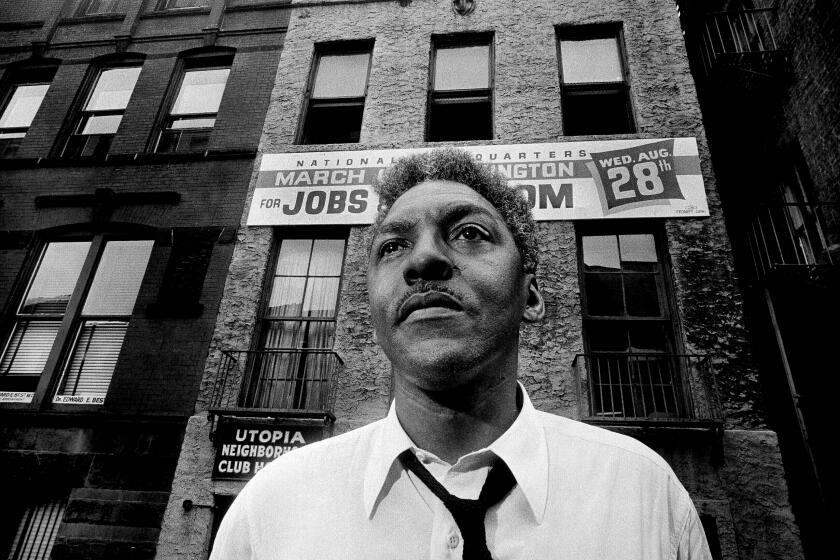

The American civil rights hero the Rev. James Lawson Jr. isn’t as well known as his friend and colleague Martin Luther King Jr., who called him “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.”

But on Friday, as Lawson turns 95, progressive leaders in Los Angeles will be honoring the role he played in training a new generation of activists to apply the civil rights movement’s lessons to the 21st century.

Opinion Columnist

Jean Guerrero

Jean Guerrero is the author, most recently, of “Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump and the White Nationalist Agenda.”

Los Angeles City Councilman Hugo Soto-Martinez, who led the council’s decision this week to declare Sept. 22 as “Rev. James Lawson Jr. Day” annually in the city after L.A. County made a similar proclamation, describes him as the “godfather of the civil rights movement.”

Soto-Martinez thinks it’s crucial that more people learn Lawson’s strategies. As he told me, if we’re going to curb the polarization of America, “we need to see how these tactics are incredibly helpful.”

As a young man, Lawson spent 13 months in prison for refusing the Korean War draft, then traveled to India to study the practices of Mahatma Gandhi, who had won India’s independence from British rule with nonviolent resistance, or satyagraha. When he came back to the U.S., Lawson met King, who recruited him to train hundreds of civil rights activists in those tactics, preparing them for the lunch counter sit-ins, freedom rides and other protests that led to an end to segregation laws in the South.

Among some LGBTQ activists, resistance to bigotry means nonviolence and radical compassion. They believe hating the harassers doesn’t change the cycle of violence.

In 1974, six years after King’s assassination, Lawson moved to L.A., where he served as pastor of the Holman United Methodist Church and led training for local labor leaders and activists, including teaching a continuing class at UCLA and at Cal State Northridge.

Soto-Martinez received his first training from Lawson as a union organizer at 23. A few years later, feeling burnt out and depressed, he questioned his capacity to stay in the struggle. Lawson urged him to dive deeper into the philosophy of nonviolence, suggesting a 1934 book, “The Power of Nonviolence” by Richard B. Gregg, who also studied Gandhi and influenced King and his allies.

“Anger, hatred, and fear make an enormous drain upon our energy,” the book says. “The angry and violent man puts too much emphasis on immediate objects and too little on the ultimate impelling forces behind them.”

An activist surveyed the students and found a mental health crisis fueled by financial fears and loneliness.

Soto-Martinez realized that by acting from a place of love instead of anger, seeing opponents not as enemies to be defeated but as human beings to be won over, he could stay in labor activism his whole life. “It’s not just about fighting for the sake of fighting, but about what we are trying to build,” Soto-Martinez said.

“Reverend Lawson is under-appreciated,” said Kent Wong, the UCLA Labor Center director who co-teaches the university’s class on nonviolence with Lawson. He credits Lawson with the “revitalization of the Los Angeles labor movement.”

Lawson’s teachings have influenced everyone from national civil rights icon John Lewis to undocumented Gen Zers like Karely Amaya, a 23-year-old pursuing a master’s in public policy at UCLA. She co-led Opportunity for All, a recent groundbreaking campaign that convinced the UC Regents to hire undocumented students on UC campuses. Lawson’s class on nonviolence, Amaya told me, made “it possible to see what we could do as undocumented students.”

The film is a rare product of mainstream culture that invites men to reimagine masculinity for their own sake.

Nonviolence education will soon be taught in public schools statewide thanks to a unanimously passed resolution by state Sen. María Elena Durazo (D-Los Angeles), a longtime friend and ally of Lawson’s. The UCLA Labor Center is working on a high school curriculum based on Lawson’s teachings.

Durazo was president of the L.A. hotel workers’ union Local 11 when she reached out to Lawson for guidance. He helped her plan protests that brought national attention to the plight of immigrants, including 2003 immigrant freedom rides in which 18 buses traveled across the country to respond to rising xenophobia. Two buses were stopped by Border Patrol near El Paso, including one carrying Durazo.

Because of training that every participant received from Lawson, they were calm in the face of intimidation by border agents. “Nobody ever said, ‘Let me go, I’m a citizen,’” Durazo told me. “We all stuck together.”

As in the anti-vaccine universe, the voices of the anti-sunscreen world cross party lines at the paranoid juncture of the far left and far right.

Nonviolence has lost some of its appeal in recent years, with outrage becoming the norm in public discourse. Civilian militarization and polarization have also caused many activists to see violence as inevitable.

The assault on human rights is coming from all directions — against people of color, women, immigrants, the LGBTQ+ community and others. Because the monster now has so many heads, it’s harder to expose the evil than when the villain was segregationist laws in the South.

“We don’t have a single enemy,” said Gary Orfield, co-director of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA. “The enemy is structures of inequality that need to be dismantled. And there’s no strong consensus about how to do that.” Even in deep blue California, well-known solutions to end the legacy of racism such as affirmative action and reparations lack popular support.

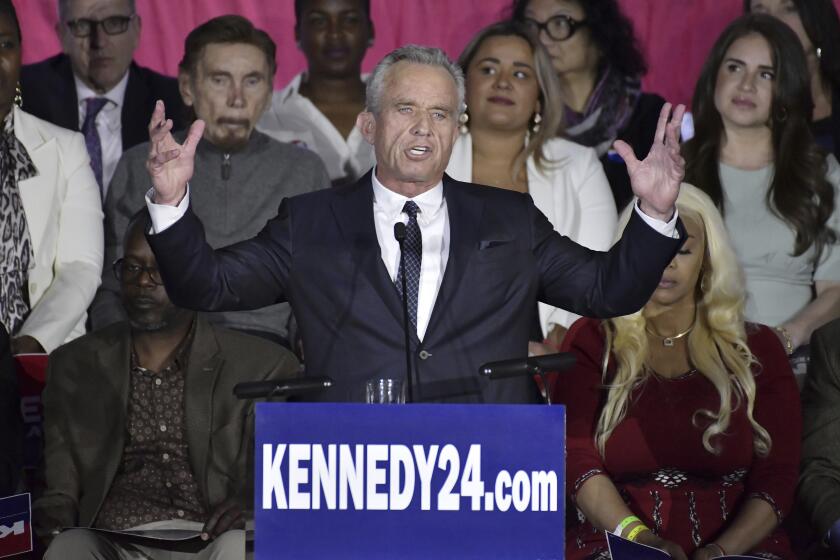

Kennedy’s popularity on Los Angeles’ Westside, a hot spot of ‘conspirituality’ — where wellness and spirituality meet conspiracy theories — shows a growing left-wing distrust in democracy.

But satyagraha is the only sound solution. As the book Lawson suggested to Soto-Martinez states: “Peace imposed by violence is not psychological peace but a suppressed conflict. It is unstable for it contains the seeds of its own destruction.”

Karen Hayes, the director of a forthcoming documentary about Lawson’s life, “A Better Way,” says, “A lot of people see nonviolence as only reacting, they see it as passive, when it’s actually radical. And it is disruptive.”

Years ago, Lawson cordially asked a white man who had just spat in his face if he could borrow a handkerchief in his pocket. The man was so taken aback that he gave it to him without comment. “In that moment, Reverend Lawson is saying to that person, ‘Actually, I forgive you for doing that,’” Hayes explained to me. “‘I see your humanity. I think enough of you that you will help me.”

She says he preaches that people who act inhumanely do so because they’ve lost sight of their own humanity. In some cases, it’s possible to help them find it.

Put into practice, Lawson’s teachings can change us all. Perhaps they even can heal our deep social divides.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.