Opinion: The price of being Black in a small town — La Cañada Flintridge

On a recent Friday night my wife and I watched in stunned confusion as a man in a pickup truck tried to intimidate our son and, possibly, goad him into an incident that could have ended in tragedy.

First, some context. My wife, my son and I are Black. The man in the pickup truck was white. Our family home is fenced and gated in La Cañada Flintridge. The incident occurred in front of our house as my wife and I sat on our second-story balcony overlooking the street, awaiting our son’s visit.

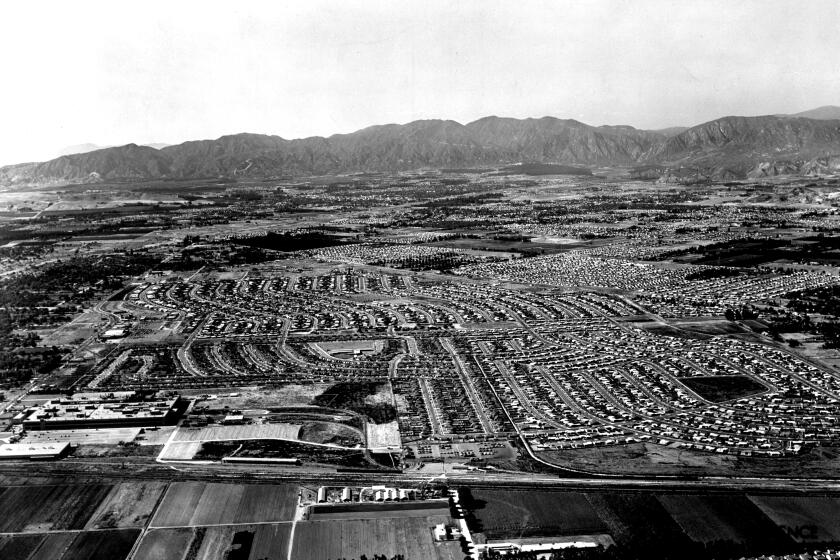

And some history: La Cañada Flintridge has a reputation as a former “sundown town,” a community where Black people were unwelcome — subject to harassment, violence and arrest, especially after dark. Race restrictions, housing covenants, real estate agents’ policies and policing practices prevented Black people from living or owning property here for decades. Even now, the residual effects of these factors have kept the town’s Black population at just 1.2%, according to the latest U.S. census estimate.

After real estate agents invented racial covenants in the early 1900s, L.A. led the nation in using them. Their idea of ‘freedom’ shapes the U.S. today.

On July 28, our son, 27, stopped by at about 8:35 p.m. Rather than coming inside immediately, he parked by the front gate, engine idling, with the windows closed, as he finished editing a video on his phone. Nine minutes later — we know it was nine minutes because our security camera captured the events — a black pickup truck approached him from behind, slowed to a crawl and double-parked next to his car, blocking his exit.

My wife and I looked at each other, and I thought, Does he know the truck’s driver? While I was trying to make sense of what was happening, my wife instinctively leapt up and ran downstairs, out the front door and across the yard.

Frightening scenarios flashed through our minds fueled by two things: our own experiences in La Cañada, where we’ve been targeted, harassed, followed and questioned, and the sickeningly familiar pattern of vigilante attacks on young Black men in predominantly white neighborhoods. Ahmaud Arbery and Trayvon Martin are only two of the many who come to mind.

Every metropolitan area in the nation is racially segregated, and Los Angeles is no exception.

Meanwhile, the truck’s white driver — in his 60s, with slicked back, graying hair — leaned across the passenger seat and spoke loudly enough that I heard him from my balcony perch yards away: “Got something special going on tonight?”

Our son, always the gentleman, replied, “Beg your pardon?”

The man repeated the question, sounding accusatory this time, leaning closer to the passenger-side window: “Something special happening tonight?”

As the decibel level rose, my wife called out to our son: “Hey, do you need help?”

When he answered calmly, “Yeah, I think I might,” we could hear the fear in his voice.

“Them: Covenant” on Amazon Prime is a reminder of the all-too-common housing covenants that restricted who could buy homes in certain neighborhoods in Compton, around Southern California and elsewhere. Determined Black people over the decades fought for their rights to live where they pleased.

My wife began shouting at the man in the truck: “What the f— do you want? Get out of here! Leave him alone!” She told our son to get off the street, to drive his car through the gate.

He started forward slowly, turning into the driveway, then hesitating to get out to punch the keypad because, he said later, he thought stepping out of the car might be perceived as a threat.

Finally, the white man in the black truck took off. We watched him turn at the corner, heading deeper into the neighborhood that we call home.

The entire incident lasted all of 70 seconds, but it was interminable as it unfolded. After all, it takes only seconds to pull a gun (I have to wonder if he had one) and take a young man’s life.

When we reviewed the security footage, we saw new details. The black truck had gone by twice, passing my son’s car from the opposite direction, before the driver turned around and pulled up next to him. Did the driver think it was his duty to circle back to investigate? What made him feel entitled to stalk and question a young Black man parked on a residential street in La Cañada?

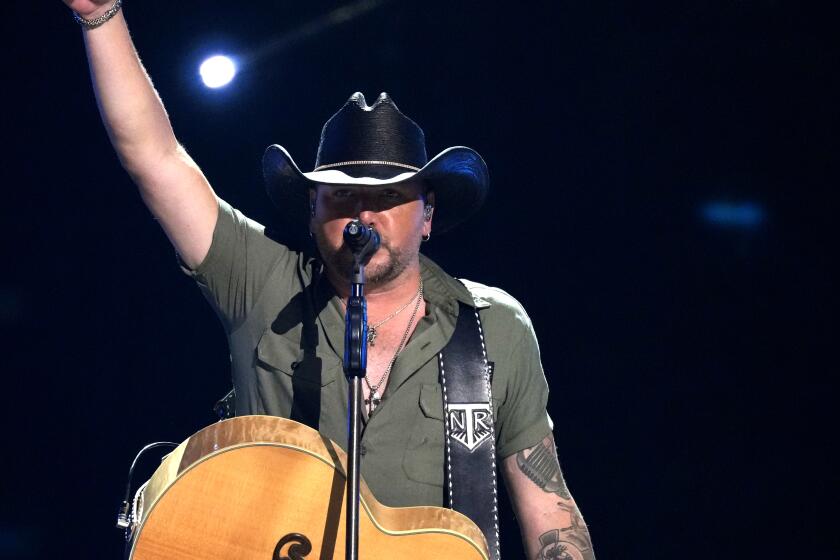

Singer Jason Aldean says critics who think his ‘Try That in a Small Town’ is about lynching or race are making ‘meritless ... dangerous’ allegations.

We called the Sheriff’s Department a little while later, to put the incident on the record. Three officers came by and heard the story. They told us no crime had been committed, and they declined to make a report. They didn’t take us seriously enough to review our security footage.

We are shaken. We know there is a sad and deadly truth about what might have happened, especially in a nation where newly emboldened racists dare unnamed “others” to “try that in a small town.”

Brian Williams is the chief operating officer of the Weingart Foundation.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.