Opinion: Violence against Black women and girls is underreported. Here’s how we can address it

Violence against Black women and girls is a longstanding national epidemic that has long been overlooked and underreported. Though they make up less than 5% of Los Angeles’ population, Black women are far more likely to experience multiple forms of violence and trauma than other groups.

According to a March report by the L.A. City Civil and Human Rights and Equity division, from 2011 to 2022, Black women made up one-third (32.85%) of female homicides and nearly one-third (28.2%) of all missing women. During this period, they also were nearly one-fourth (22%) of all female rape victims. In comparison to non-Black women, Black women are three times more likely to be killed by an intimate partner.

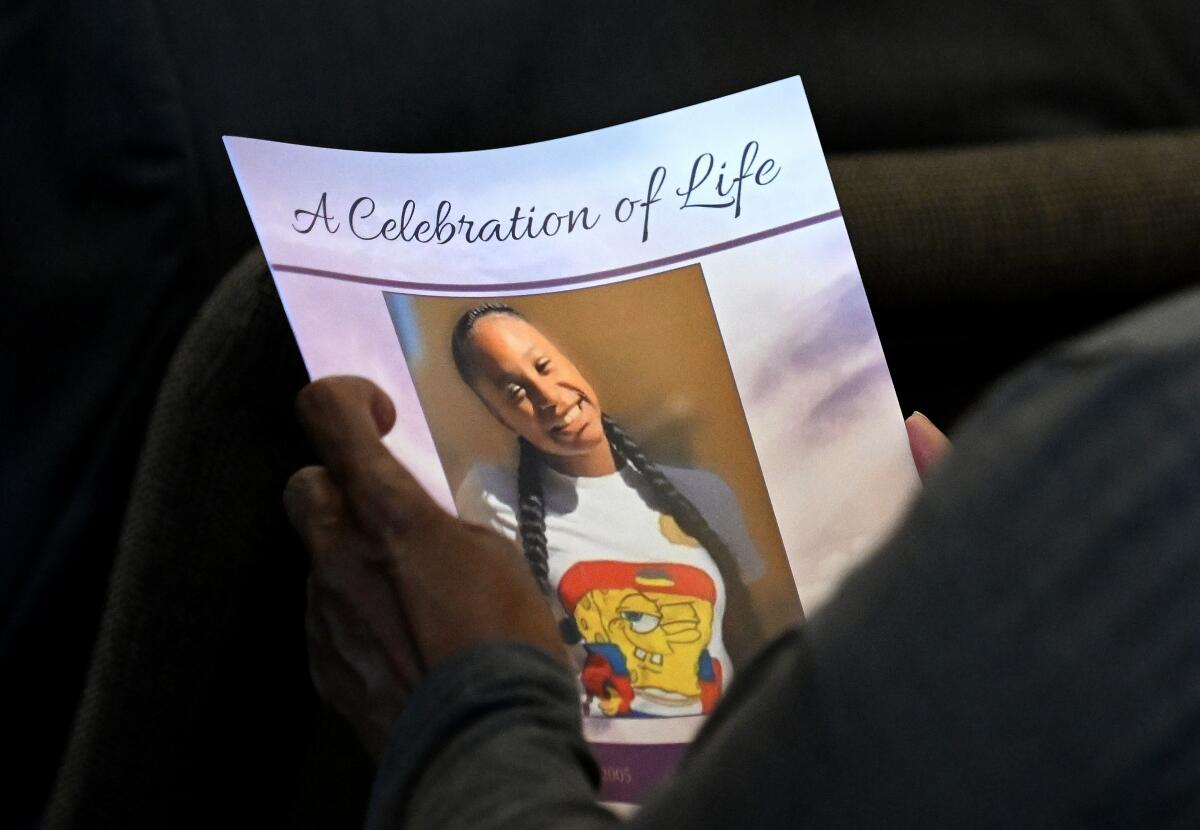

The report was commissioned by the L.A. City Council as part of a January 2022 motion requesting an equity analysis on violence against Black women and girls. The motion cited the case of 16-year-old Tioni Theus, a missing African American high school student whose body was dumped on the side of the 110 Freeway early last year. Theus’ unsolved slaying elicited outrage within the African American community because of the initial dearth of coverage on her killing.

Unequal coverage of missing Black women and girls is part of a long national pattern. While missing white women and girls often become memorialized in TV specials and “Dateline” episodes, missing women of color rarely receive the same treatment. Although the City Council increased reward money for information on Theus’ killing, the lack of local government programs dedicated to the specific plight of Black girls continues to be glaring.

Underinvestment in the needs of Black women and girls in the private sector dovetails with a lack of public sector investment in culturally responsive violence prevention, mental health and school-community programs. The city’s report highlights the valuable work of several local domestic and sexual violence victim advocacy agencies.

However, violence prevention education programs that are specifically tailored for Black girls and Black gender-expansive youth are few and far between. And they constantly struggle for funding and visibility. L.A. could play a crucial role in violence prevention by creating more community youth centers in South L.A. There are few dedicated safe spaces for youth in Council District 8, which has one of the highest Black populations in the city.

Black teens and young adults need stable access to youth-serving programs where they can receive job training, academic preparation, social-emotional support, mentoring and professional development, in addition to sexual and domestic violence prevention education training.

These initiatives should incorporate trauma-informed approaches that take into account the deep social impact of family and community violence on Black female-identifying sexual and domestic abuse survivors. Black women and girls are more likely to be victim-blamed and shamed for their experiences. Toxic racial and gender stereotypes about Black female sexuality, criminality and the presumed lack of innocence of Black women, make survivors more susceptible to being disbelieved by law enforcement and folks in their own communities.

Racist perceptions about Black women also lead to disproportionately high rates of arrest and conviction for sex trafficking. And high rates of incarceration and policing dissuade abuse victims from coming forward for fear that they or their loved ones will be jailed. It’s estimated that only one in 15 Black women rape victims report their abuse to the police.

The March report also highlights the problem of dual arrests, in which victims who are involved in physical conflict with their abusers wind up getting arrested themselves. Such dual arrests should end. The city should also deploy community violence “disruptors” and mental health outreach specialists (rather than police), who are better equipped to deal with such abuse incidents.

Interlocking factors related to race, gender identity and transphobia also drive the homicide epidemic among Black trans women. Nationwide, Black trans women have the highest homicide rates in the LGBTQIA+ community. Compounding this fact, murders of Black trans women aren’t adequately captured in L.A. city data because law enforcement and reporting agencies haven’t been trained to capture multiple protected class identities. Misgendering of trans women also contributes to their invisibility in crime victim data.

The L.A. civil rights report is a devastating snapshot of the crisis confronting Black women. Unfortunately, government officials have a long history of paying lip service to community-based engagement while creating roadblocks and red tape for grassroots organizations doing the work. Rather than perpetuate this pattern, the city has to make supporting culturally responsive solutions to reducing violence against Black women and girls a greater priority.

Sikivu Hutchinson is the founder of the South L.A.-based Women’s Leadership Project and the author of “Humanists in the Hood: Unapologetically Black, Feminist, and Heretical.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.