Opinion: My son the vandal — and the untreated, unaddressed epidemic of mental illness

In a courthouse hallway in Los Angeles in early May, I begged my son’s public defender to advocate for a mental health program where he could get the treatment he needed.

She wasn’t listening, not to me or my husband or Soma Snakeoil of the Skid Row nonprofit Sidewalk Project, who advocates for our son.

At age 34, plagued with mental health and addiction issues, our son has lived unhoused for almost a third of his life — beneath trees, on sidewalks, in abandoned buildings and inside the cab of a truck.

Now he was in court because of an outstanding 2020 bench warrant for felony vandalism. He’d broken windows in a commercial building because he saw “something evil” reflected there, causing approximately $40,000 in damages.

When he was late to the hearing, the public defender said, “He must be having trouble parking.”

Parking? “He hasn’t had a car or a driver’s license in years,” I wanted to say. She’d turned away. He was her client, not us, his parents.

Our son has schizoaffective disorder with depressive episodes. He had gotten picked up on the bench warrant in October, jailed until a competency hearing in April — which he passed — and then released pending the May court date. After the release, things had not gone well with him. But the competency decision was still in force.

If only it had still been accurate. During his months of incarceration, his father or I had spoken with him daily, and we visited weekly. We sent care packages, letters and books. So did friends. He read a lot: “The Count of Monte Cristo,” “My Ántonia,” “On Gold Mountain,” “Anna Karenina” and lots of Jackie Collins.

While inside, he refused meds and regaled us with impersonations of doctors who visited him. But housed and free of drugs, he grew interested in his family again.

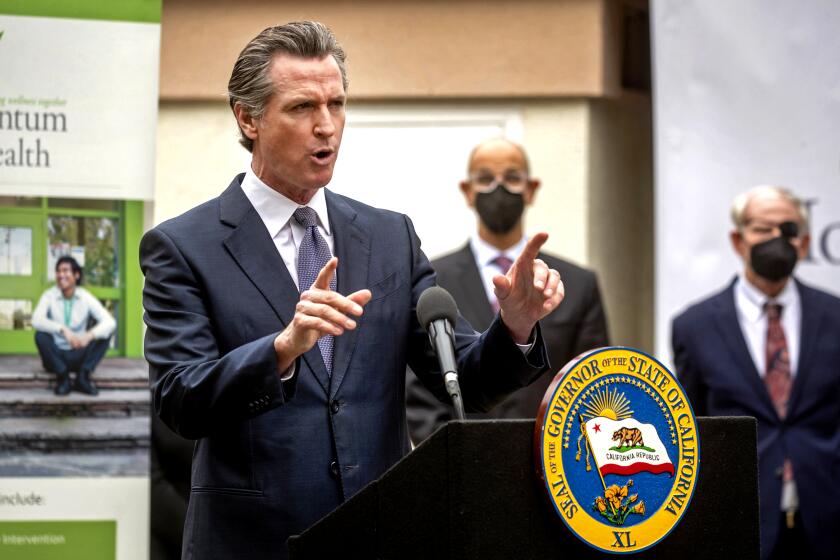

There’s a bipartisan attempt in the California Legislature to finally finish the mental health reform that Gov. Ronald Reagan and lawmakers began 56 years ago.

How was his new nephew doing? His siblings? He asked about our rehearsals with the Silverlake Singers and recommended that we drink tea with honey and lemon to keep our voices healthy.

I told myself, even if he goes out again, at least we’ve had these months. Our son was back, albeit behind thick glass during visiting hours or calling on prepaid cards from a jail phone.

The day after the April competency hearing, my son was supposed to answer for the broken windows. But the prosecutors weren’t ready. We were in the courtroom that day too. When his public defender argued for my son’s release, she explained that he’d be staying with a girlfriend in Inglewood.

“So the parents are unwilling to accept him into the home?” the judge asked. She stared at us.

We weren’t sure how to respond. We knew from long experience we couldn’t run a rehab for him or be his jailers. But he’s our beloved son. Maybe this time we could figure it out.

“We’ll accept him,” I said.

Our son smiled at us in his jail clothes from the holding box.

His release took 24 hours to process. He walked home from Twin Towers to Echo Park in the rain. For several days, we cooked dinners, attended a film festival, made lunches with the Hollywood Food Coalition, reconnected with family, and he played the piano.

Then it started. I spent 15 hours trying to get him to stop harming himself as he “removed” nonexistent mites from his face with bug spray, avocados, soup, chocolate, hydrogen peroxide, shaving cream, candle wax and turmeric.

I sent texts, photos and videos to his public defender to keep her informed of his mental state. With the help of the county Psychiatric Mobile Response Team, our son was placed on an emergency psych hold. A week later, the hospital released him with bus fare to Inglewood. We’d asked for a longer emergency hold, the better to get his meds and his life regulated.

We got nowhere.

Our family is by no means unique. We’re part of an untreated, unaddressed epidemic.

When our son is not using, he is still psychotic, and his delusions are poetic and cinematic. He is convinced that Germans invented time travel. He can summon the year 1890 with broken headphones, which allow him to hear the old trolley cars in L.A. He’s fixated on local history, old Hollywood and baseball: Jean Harlow, Mayor Tom Bradley, Bob Gibson. When he was arrested on the bench warrant in October, he carried only a baseball and glove.

Seven counties will open their CARE Courts on Oct. 1. The state has estimated that 7,000 to 12,000 people will qualify for a treatment plan.

He doesn’t want treatment. He’s lived a feral life on the streets. During the pandemic, he stayed in hotels as part of Project Room Key, and we’d take him for picnics. But, according to him, the water in the showers weakened his joints and it was back to the streets.

We try to understand, why him, why us? Our son has been our greatest teacher. As a young mother, I thought if you loved your children and helped them pursue their dreams, it would be enough. It’s not enough, and it never will be when you’re grappling with the twin monsters of addiction and mental illness.

My son finally made it to the May hearing. In the courtroom, Soma Snakeoil attempted to explain the odyssey he’d been through, what we’d been through — would the court hear her out? The judge just said, “I don’t allow questions in my courtroom.”

His jail time was taken into account. He was put on probation and assigned community service.

When we walked out of the courthouse, Soma asked him what he needed. “Trust and communication,” he said. He would be “open” to the Sidewalk Project’s offer of housing and medication. He sounded rational, if you didn’t know better.

His father hugged him goodbye and went to work.

Public defenders, prosecuting attorneys and judges in L.A. work together to order treatment instead of incarceration for defendants whose crimes arise from mental illness.

Then my son and I sat on a bench in Grand Park by City Hall. He rolled up his sleeves and showed me his arms, skin raw from scraping.

He said, “Why are you crying? I didn’t do it! It was zappers. They got me.”

We talked in circles. He wanted my coat because the ”zappers” had also ripped a hole in his pants.

“No,” I told him. “Sorry, I love this coat.”

“Then buy me new pants, come on, Virginia Woolf. Don’t look so doom and gloom. You don’t know my life. I’m fine. I’m great.”

When we hugged goodbye, I left him standing on Grand Avenue by the Music Center afraid he would follow me, afraid he wouldn’t. He didn’t.

I headed for the bus stop, and Echo Park, walking home through the hills, listening to wind chimes and leaf blowers, the sounds of an ordinary Monday in the city.

Kerry Madden-Lunsford lives in Los Angeles and Alabama, where she is a professor of creative writing at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Her forthcoming children’s novel is “Werewolf Hamlet.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.