Editorial: Popular LAUSD program was helping struggling students. So why was it cut?

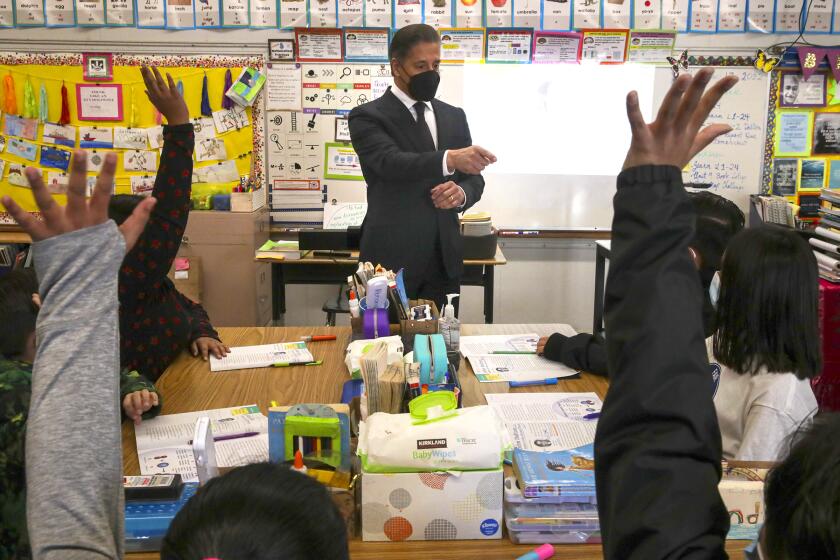

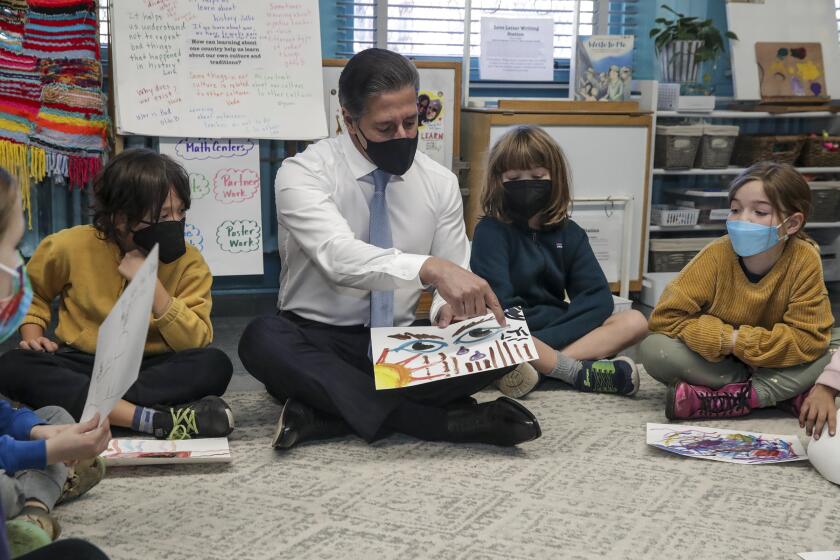

In August 2020, Los Angeles Unified School District launched a program to help students struggling with reading at a time when many were already suffering learning gaps worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic school closures. Then-Supt. Austin Beutner touted Primary Promise as an academic intervention program that paired specially trained teachers with small groups of K-3 students.

The program showed results within months, and was expanded to more students and to include math. In April 2021, a report from the educational consulting company District Management Group said that the program had quadrupled participants’ reading fluency and doubled reading accuracy. District officials praised the program for helping the neediest students, such as those in foster care, with disabilities or without permanent housing.

A year later, however, LAUSD officials have slashed funding for Primary Promise, reducing the programs that served more than 300 schools. Officials claim the program is expensive, pulls experienced teachers from their schools and only reaches a limited number of students. Instead, the district plans to debut a new intervention program they say will benefit students at all grade levels and will not rely on limited-time use pandemic funds.

LAUSD has had months to fine-tune its Acceleration Days program, yet many parents are frustrated with the lack of information about a month before the program starts.

OK, but Supt. Alberto Carvalho, L.A. Unified board members and other district leaders need to give the public a better explanation for the abrupt reversal on a popular program, particularly because research shows this kind of one-on-one learning intervention is most helpful for struggling students. Understandably, some parents and teachers are upset that the program is being scaled back. They worry that the new program will set back students if they don’t have the same high-quality, small-group intervention and targeted assistance.

The new program, called Literacy and Numeracy Intervention, will provide struggling students in high-need schools with daily small-group instruction. The district plans a presentation about the new academic intervention program at the June 6 board meeting, and should also provide data that support replacing Primary Promise with Literacy and Numeracy Intervention. District leaders also need to give parents and teachers more than one opportunity to discuss the change, otherwise they are likely to feel as if the rug has been pulled out from under their feet.

That’s no way to get buy-in from parents and teachers, particularly after the recent fumbled rollout of another high-profile academic intervention program, Acceleration Days. The voluntary program to make up for learning loss was costly, but had low turnout in part due to poor communication with parents and teachers. These moves do not inspire confidence in LAUSD leadership, even if Carvalho and the board are trying to do the right thing and for the right reasons.

The latest national proficiency test scores offer a desolate picture of students’ academic achievement, showing that we need immediate action to fix the learning loss. But there are pockets of hope, among them reading scores for LAUSD eighth-graders.

District leaders should understand that people will have difficulty letting go of a program that, even by LAUSD’s own accounts, has been highly successful. The independent advocacy group Equity Alliance for L.A.’s Kids, which focuses on helping kids in highest-needs schools, even mentioned the program in its April 2021 report, “Racial Justice Equity Plan for Recovery,” as a long-term strategy to ensure the academic success of the neediest students.

Students in Primary Promise showed not only academic gains, but gained confidence as well. The program, which started with 2,500 students in first grade, expanded to 14,000 students and other grade levels by the following school year. In an online petition to try to save the program, teachers and parents made comments such as: “My students are readers now!” and “They are confident and love school.”

It makes sense that the district would want to alter its learning acceleration program, as its main source of funding is set to run out at the end of September 2024, and to expand the strategy to other grades. But it needs to be upfront and transparent about what it is doing, and not simply scrap one popular program for another untested one without explanation.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.