Column: How Donald Trump’s abhorrent character made E. Jean Carroll’s case

A federal jury found Donald Trump liable for sexually abusing and defaming the writer E. Jean Carroll on Tuesday after less than three hours of deliberation, delivering a quick and devastating verdict on the conduct and character of the former president.

The plaintiff showed remarkable courage and credibility over the course of three days of draining testimony, especially under cross-examination. Trump attorney Joe Tacopina scored few points and lost many more in his overbearing and overlong attack on Carroll.

But as much as Carroll’s heroism, it was Trump’s extraordinary villainy that sealed his fate.

Consider the facts of the case apart from the involvement of a former president of the United States: A woman meets a man in a department store, engages in flirtatious banter with him and follows him into a dressing room, where he allegedly assaults her. She doesn’t report the episode for 30 years, and neither do her friends who ultimately show up to testify that she told them about it decades earlier.

Such a case sounds like an uphill battle. Most lawyers would shy away from bringing it based on the strong possibility of a verdict for the defense.

What made the difference in this case is the character of the defendant and the plaintiff’s success in demonstrating it to the jury. Over eight days of testimony, Carroll showed Trump to be a bully, a coward and a predator.

The writer sued the ex-president alleging sexual assault and defamation. The law and evidence in the case, which went to trial Tuesday in New York, favor the plaintiff.

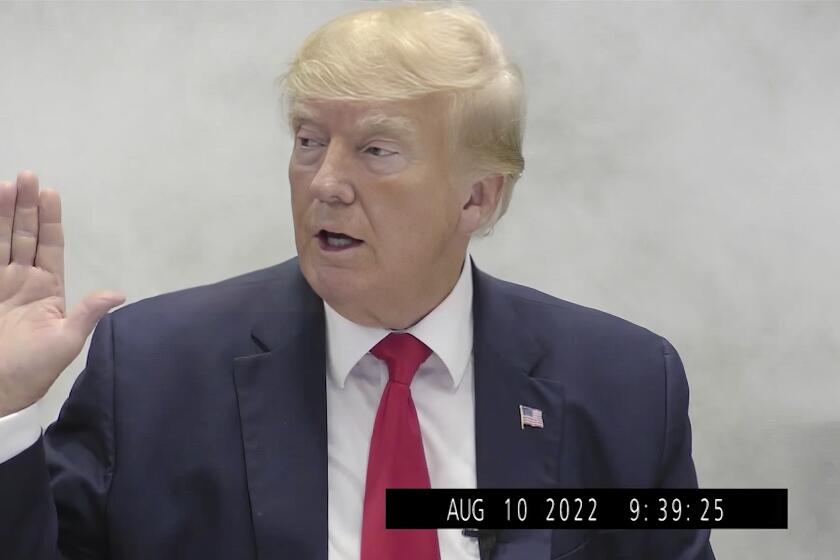

Trump’s instinct as a bully is to humiliate and vilify his critics. Rather than simply deny Carroll’s allegations, he insisted on demeaning the case as a “scam” and Carroll as a “wack job” who was “mentally sick.” His truly Trumpian coup de grace was that the plaintiff was not his “type” and that there was “no way I would ever be attracted to her,” a gratuitously vicious slur that came back to haunt him when he confused Carroll with his ex-wife Marla Maples in a generally disastrous deposition.

Moreover, notwithstanding his repeated swashbuckling claims that he wanted to defend himself in court, Trump revealed his cowardice by turning tail and failing to do so. People with trial experience (including me) predicted as much: Trump’s long record of lies would have ensured a bloodbath of a cross-examination and possibly exposure to multiple counts of perjury. Trump, who has spent most of the last few years desperately trying to avoid consequences for his conduct, has a well-known tendency to talk big and then fold.

Worse, Trump’s refusal even to show up in court almost certainly alienated the jury and allowed Carroll’s counsel to have a field day in closing arguments.

“He never looked you in the eye and denied raping Ms. Carroll,” Carroll attorney Michael Ferrara told the jury. “You should draw the conclusion that that’s because he did it.”

Trump’s pugnacious lawyer had no viable response to this line of argument.

Cases brought by Alvin Bragg and E. Jean Carroll put the ex-president in the impossible position of having to take the stand to make much of his case.

Most damningly, the evidence revealed Trump to be a sexual predator. The federal rules of evidence helped here, permitting the former president to be judged for his propensity to assault women based on his prior similar behavior.

The rules in most cases prohibit the introduction of prior bad acts to suggest that a defendant did it before so you can bet he did it this time. That line of argument goes against our general social and legal commitment to judge a defendant based on conduct rather than character.

But Congress has authorized such evidence in cases of sexual assault. U.S. District Judge Lewis Kaplan accordingly instructed the jury that evidence that Trump previously engaged in sexual assault could be considered as to his tendency to do so again.

The jury was therefore able to consider the testimony of two of Trump’s other alleged victims, Jessica Leeds and Natasha Stoynoff, who had no conceivable reason to make up their stories, and conclude that if he did it to them he probably did it to Carroll.

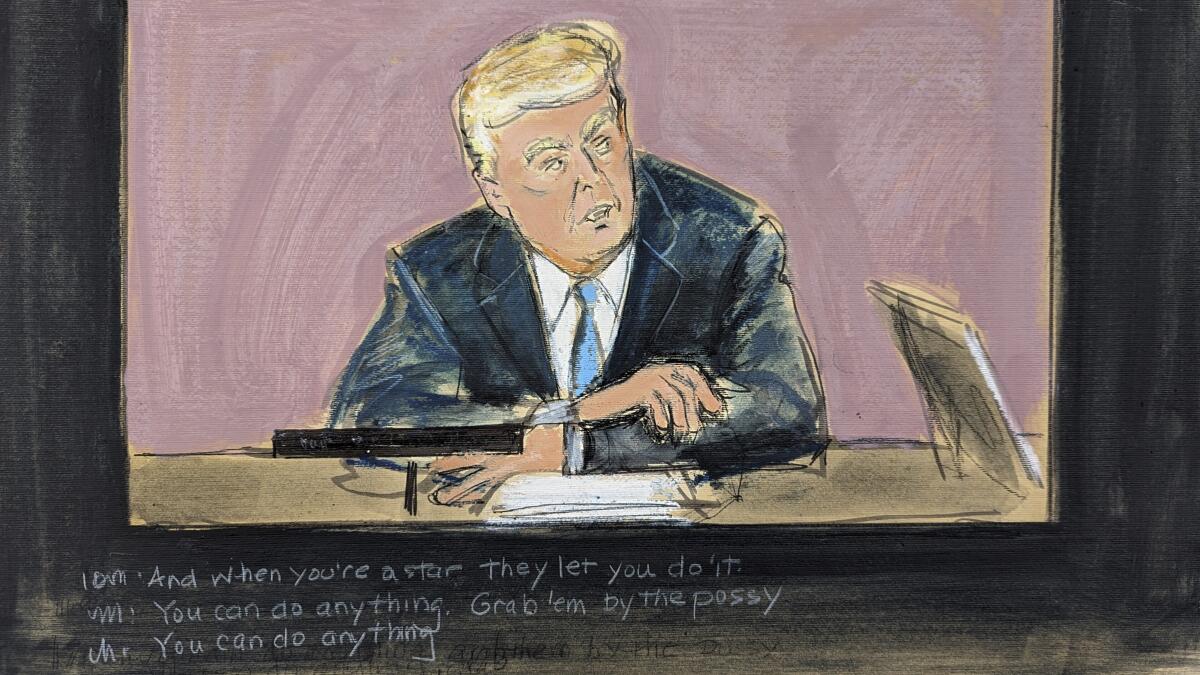

Perhaps the most memorable and damaging evidence of Trump’s propensity for sexual predation consisted of his own words on the infamous “Access Hollywood” tape: “I don’t even wait. And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab ’em by the pussy.” As Carroll’s lawyer argued, this was more evidence of Trump’s abhorrent character: Trump had revealed “in his very own words how he treats women.”

The damning verdict will of course be ignored by the fraction of the electorate that is willing to overlook or ignore every one of Trump’s transgressions no matter how grave. But for the rest of us, the verdict stands for far more than his misconduct on one afternoon in 1996. It’s a judgment of a character that is by leaps and bounds more loathsome than that of any other figure to occupy the presidency.

Harry Litman is the host of the “Talking Feds” podcast. @harrylitman

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.