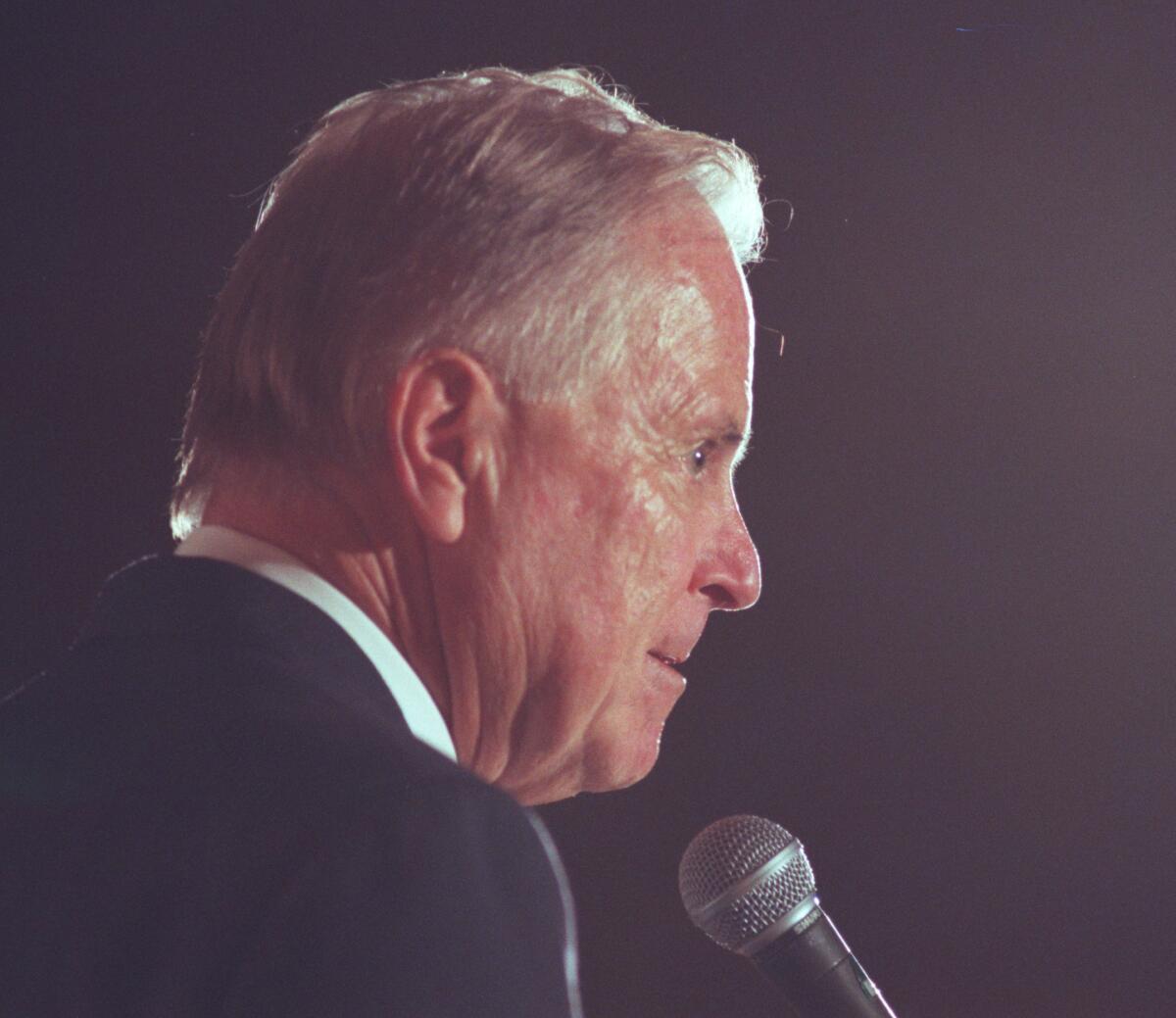

Opinion: The mayor who ‘could see around corners’ made L.A. a better city

Mayor Richard Riordan could be cantankerous. When I was covering his administration, he would often call me as soon as he’d rushed through his morning paper, and he would howl in anger. No person has ever yelled at me more regularly or furiously than Riordan did from 1993 to 2001 — often about stories I had nothing to do with. I would see him a few hours later at a press event or somewhere around town, and he would greet me cheerfully, as if nothing had happened.

But if Riordan could be challenging, he also was effective. He achieved big things in a city that badly needed help. He came to office on the heels of the 1992 riots, which had shaken L.A.’s confidence. The Los Angeles Police Department was a shambles, rocked first by its violent treatment of Rodney King and then by its lethargic, cowardly response to the riots. The economy was in the tank. A year after Riordan took office, the Northridge earthquake bounced the rubble.

Mayor Richard Riordan leaves Los Angeles better than he found it--safer, more prosperous, more optimistic about its future.

By the time Riordan left office, the city was vastly improved, not perfect, to be sure, but on its feet. Riordan partnered with the White House — he and President Clinton developed a fondness for each other — to rebuild the city after the earthquake. In fact, though he never said so publicly, Riordan believed the earthquake was good for L.A. It focused resources on recovery and helped it rebound from the recession of the early 1990s.

And on safety, the issue that brought him to office, Riordan’s record was powerful. He added police, and crime plunged. The year before Riordan took office, 1,092 people were murdered in Los Angeles. In his final year as mayor, 654 Angelenos died by homicide. Crime overall was similarly down. That’s a lot of saved lives and safer streets.

Riordan’s final gift to the city was his role in launching the effort that rewrote the city charter. Typically for the mayor, that started from frustration.

A businessman at heart, Riordan couldn’t believe that he wasn’t allowed more authority over city departments, and he was particularly irritated that he couldn’t direct the city attorney’s office. He wanted to hire and fire department heads, and he wanted to be able to pick his own lawyers, but he set in motion events that he could not entirely control. One charter commission became two, the city council got its hands in the pie. It did not turn out exactly how he’d hoped — Los Angeles mayors still do not control the city attorney — but the new charter did streamline City Hall and create new neighborhood representation. It would not have happened without him.

In his long public life in Los Angeles, including eight years as mayor, few ever accused Richard J.

I got many glimpses of Riordan’s capacity — he regularly clocked me at chess — but one stands out. It was during the tedious efforts to bring a football team back to Los Angeles. Two groups of would-be owners were vying for position, while the NFL played its own games. I asked Riordan if he would be willing, off the record, to lay out the state of the negotiations. Somewhat to my surprise, he agreed.

We sat in his office late one afternoon. He reclined on his couch, nibbling snacks — peanut butter, if memory serves — and laid out the whole thing: who was talking to whom, who was telling the truth, who was lying, what would happen next. He did it almost in a trance. Everything he predicted came true. It was an example of what one of his shrewdest advisors described as his ability to “see around corners.”

And yet, he could miss what was right in front of him. He was the guy who carried a hamburger to a hunger strike (gardeners were protesting a proposed city ban on gas-powered leaf blowers; I mean, really — only in L.A.). He took off for France on a bike trip during a transit strike. (I reached him on that trip, and he was furious. He hated “gotcha” questions and he knew one was coming.) Yet he was something of a Teflon mayor. His gaffes might have damaged another politician; coming from Riordan, they seemed more charming than malicious, more Mr. Magoo than Scrooge.

Once, at a meeting at The Times, he started fuming and stood up to storm out. Trouble was, he’d taken off his shoes. Foiled, in his stocking feet, he sat back down and the meeting moved on.

One more story: Well into his second term, Riordan was at a party in Pasadena, a going-away event for a senior member of his staff. I was there, too, and I had brought my son, who was then about 2 years old. My boy and I ducked out of the party for a few minutes and went outside.

Former L.A. Mayor Richard Riordan has endorsed developer Rick Caruso for mayor, according to a release from Caruso’s campaign.

We came upon Riordan, all by himself, on a patio overlooking a pool and grounds. Riordan liked my son, who was born just before Riordan’s reelection in 1997, and we chatted for a while about being dads. Looking out over a darkened garden, Riordan reflected on the deaths of his son and one of his daughters. He was tender and vulnerable, so different from either the Mr. Magoo or the deal maker that the public most often saw. I was reminded of how his life — so outwardly successful — also was riddled with sadness, and how he overcame it.

He was a difficult man, and we did not always get along. But he had a generous heart. He cared about Los Angeles deeply, and he dedicated himself to its improvement. He left it better than he found it.

Jim Newton covered Los Angeles City Hall as a reporter, columnist, bureau chief and editorial page editor for The Times from 1992 to 2014. He now edits Blueprint magazine at UCLA and is a regular contributor to CalMatters.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.