Opinion: Will the Texas judge’s abortion overreach be matched by the Supreme Court?

Last week, dueling rulings threw the fate of the abortion pill mifepristone into doubt.

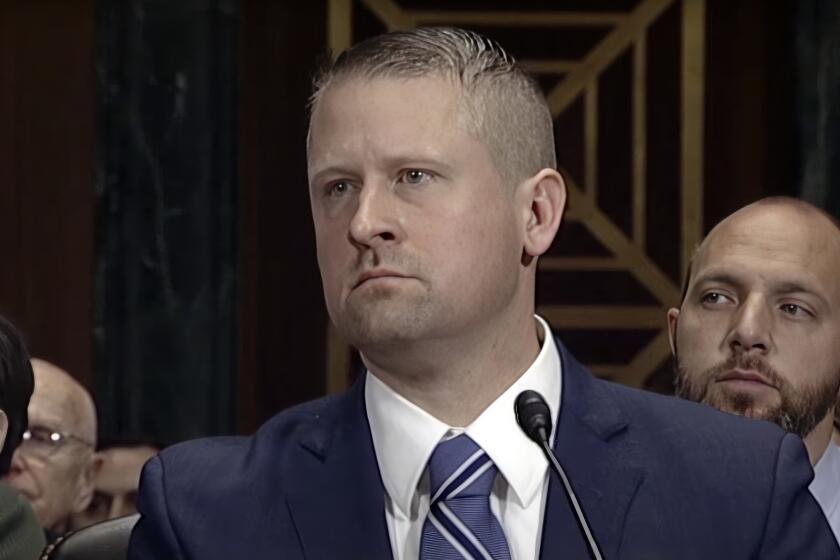

In one decision, 17 liberal states and the District of Columbia had sued to expand access to the pills, but U.S. District Judge Thomas O. Rice did not go that far, instead ordering federal regulators to preserve access to mifepristone in just the states that sued. In the other case, the Alliance Defending Freedom, a right-wing litigation group, argued that the Food and Drug Administration lacked the authority to approve mifepristone and that distribution of the drug violated the Comstock Act, a federal anti-vice law passed in 1873 and not much thought of in the past century. If Rice’s ruling was narrow, U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk gave the lawyers for the Alliance Defending Freedom everything they wanted and more.

The Kacsmaryk ruling is a reminder that far-right federal judges are increasingly unconstrained, with little fear of being reversed by the Supreme Court and no sense of accountability. If the decision reads more like an antiabortion pamphlet than a legal ruling, it also sends a clear message: The judge and others like him believe that there is nothing anyone will do about it.

Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a stockpile of 2 million abortion pills known as misoprostol after a Texas judge ruled against using a mifepristone, another medication to terminate pregnancies.

It was no great surprise that Kacsmaryk found a way to rule against the FDA. Commentators widely believed that the mifespristone case was filed in Amarillo, Texas — where Kacsmaryk presides — because he would be sympathetic to its claims.

But the breadth of Kacsmaryk’s ruling was stunning.

Ordinarily, when doctors sue on their patients’ behalf, they rely on the idea of third-party standing — essentially, arguing that their patients are not in a good position to defend their rights, and that doctors must do so instead.

But the doctors who were part of the plaintiffs group Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine said little about the harm suffered by any patients, though standing requires a concrete injury. Kacsmaryk didn’t mind — much of his standing analysis seemed like an excuse to explain why women themselves weren’t in court complaining about mifepristone. He answered this question by echoing antiabortion talking points: Mifespristone users were so plagued by “shame, regret, anxiety, depression, drug abuse and suicidal thoughts” that they needed doctors they had never met to go to court on their behalf.

The Justice Department is appealing a Texas court ruling that would halt approval of the most commonly used method of abortion in the United States.

Never mind that such claims about post-abortion mental health clash with high-quality science, or that the judge was ready to imagine a future injury to give the plaintiffs a foot in the door.

Doing far more than was necessary was the theme of the opinion.

Kacsmaryk’s decision was steeped in the rhetoric of the antiabortion movement: Doctors, in the ruling, are “abortionists;” those who choose abortion, “post-abortive women and girls;” abortion “kill[s]” an “unborn child” or “unborn human.”

Kacsmaryk first ruled that the 1873 Comstock Act, which bars the mailing of any drug or thing “designed, adapted, or intended for producing abortion,” applied to mifepristone. But by the early 20th century, federal courts had interpreted the Comstock Act to apply only when the sender intended a drug to be used unlawfully. That made it harder to pursue prosecutions, and culturally, the act came to seem like a relic. Then with Roe vs. Wade, the Supreme Court made enforcing it unconstitutional.

Antiabortion groups ‘forum shopped’ for a Trump judge likely to block medication abortion nationwide

Post Roe some of the barriers to the enforcement of Comstock are gone, but that hardly makes Kacsmaryk’s interpretation a slam dunk. The Comstock holding is explosive; it opens the door to a ban on any abortion, even in states where it is legal, since every such procedure relies on drugs and devices that might be mailed to clinics, hospitals and doctors offices.

But that was still not enough for Kacsmaryk. He went on to rule that the FDA had been wrong to approve mifepristone in 2000, setting a precedent for challenging other drugs, especially controversial ones, like those used in gender-affirming therapy.

In passing, he suggested that his ruling would save the lives of girls and women killed by mifepristone — a drug that rigorous science has established is safe and effective, safer in fact than penicillin or Viagra — and that the only benefit of abortion access was eugenic, which he connected to “the bloody consequences of Social Darwinists practiced by would-be Ubermenschen.” He even referenced the theory that a fetus is a rights-holding person under the Constitution (which matches exactly no Supreme Court decision) and that abortion is unconstitutional (ditto).

The ruling reveals Kacsmaryk’s, and much of the antiabortion movement’s, real goal: A national abortion ban, and giving science and FDA protocols a black eye.

An antiabortion lawsuit in a right-wing judge’s court claims the drug mifepristone hurts women. The case could land in the equally right-wing Supreme Court.

Kacsmaryk’s decision was stayed for a week. He knew that it would be appealed (it was, on Monday). The appeal will go to the reliably conservative judges of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, and from there to a Supreme Court packed with a majority that could well sign off on all or some of Kacsmaryk’s overreach.

The Supreme Court has had conservative majorities before, but this Supreme Court has behaved differently from its predecessors. It takes on more major cases and rules almost inevitably for conservatives — and often, delivers them bigger wins than would be necessary to resolve a case, as happened when the supermajority reversed Roe. As studies confirm that the justices have moved away from American public opinion, the court’s reputation has taken a hit: Polls demonstrate that more Americans question the legitimacy of the Supreme Court than at any time since pollsters have asked the question.

And the court has been beset by a series of scandals — the unsolved leak of the draft opinion overruling Roe, allegations that Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. gave confidential information about forthcoming rulings to conservative donors and, as of last week, the failure of Justice Clarence Thomas to disclose a series of luxury vacations paid for by conservative donor Harlan Crow.

Abortion pill ruling: A federal judge in Texas halts FDA’s approval of mifepristone, an abortion medication. But another judge contradicts the ruling.

So far, the conservative justices have not acknowledged any wrongdoing. They may see no reason to. It’s not as if the court can be held accountable. Kacsmaryk, likewise, has no obvious reason to worry that an activist opinion will be held against him in any meaningful way.

When Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturned Roe, Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh wrote a concurring opinion. In it, he promised that the court would be scrupulously neutral on abortion, treating any case on the matter with the utmost seriousness.

Kacsmaryk evidently believes Kavanaugh’s promise is meaningless. One thing is clear: Together with Kacsmaryk’s decision, the conflicting ruling from Rice has given the FDA clashing orders and created a crisis that, eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court will have to resolve.

Kacsmaryk’s ruling reads like it was written by someone already sure of a high court win. Soon enough, we will learn if that assumption is right.

Mary Ziegler is the Martin Luther King Jr. professor at UC Davis School of Law and author of “Roe: The History of a National Obsession.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.