Editorial: Carvalho’s first report card as LAUSD superintendent: a few stumbles, but he can do better

Alberto Carvalho blazed in from Florida last year with sunny optimism and bold plans to boost student performance and reverse declining enrollment in the Los Angeles Unified School District even as families were still reeling from the pandemic. His accomplishments and long tenure in leadership at Miami-Dade County Public Schools made him seem like the perfect candidate to lead the nation’s second-largest school district.

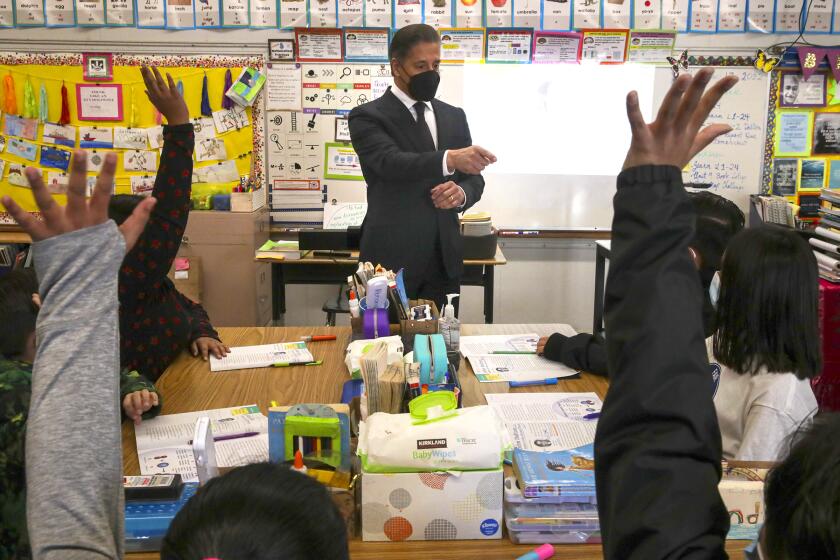

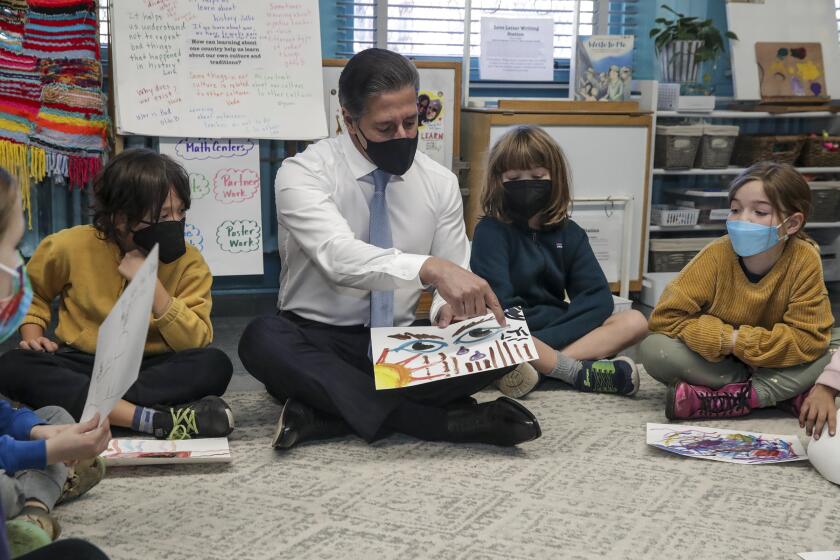

Now, Carvalho begins his second year as LAUSD superintendent with mixed reviews for his administrative stumbles, sometimes showy appearances and social media presence. And though supporters and critics say one year is not enough time to fairly assess his progress, he should learn lessons from the first year if he’s to fulfill his promises.

Carvalho met with the editorial board earlier this month to discuss his first year and his goals for the coming year. He is still as optimistic and energetic as he was when he arrived. Good. With the honeymoon period over, Carvalho will need that for the hard work ahead getting administrators, teachers, parents and students on board to reach common goals. He didn’t always get this right the first year, but his missteps offer lessons for him to do better.

LAUSD has had months to fine-tune its Acceleration Days program, yet many parents are frustrated with the lack of information about a month before the program starts.

Case in point is the rollout of the Acceleration Days program designed to help students recover from learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. The program started out weak because Carvalho failed early on to communicate with parents and teachers about the details of the plan to add four extra days to the school year.

Not surprisingly, only 36,486 students attended the two extra school days during winter break, representing less than 9% of the district’s 422,276 students. Carvalho promises that the second round of acceleration days during spring break will be better attended because district officials are trying to identify students who should be in the program earlier in the process. Additionally, the district plans to contract with tutoring companies to offer students more individualized attention. We hope so. Students, especially those who are low-income, show steep declines in math and reading achievement, according to national and state proficiency test results released last fall.

Carvalho’s willingness to adjust his plans is important. He handled two major emergencies in the last year with aplomb, even if the results were not perfect. A cyberattack discovered in the fall substantially disrupted district operations for at least a couple of weeks. Details about the data that were compromised are still being uncovered to this day, though swift work by technicians averted further harm. And after several overdoses and the fentanyl-related death of a 15-year-old student in September, Carvalho authorized every school in the district to stock naloxone, a medication that counteracts opioid overdoses.

He also deserves credit for working with the school board to develop the district’s first four-year strategic plan, which aims to elevate academic achievement, especially for students who are disabled, learning English, low-income, in foster care, and Latino and Black.

The latest national proficiency test scores offer a desolate picture of students’ academic achievement, showing that we need immediate action to fix the learning loss. But there are pockets of hope, among them reading scores for LAUSD eighth-graders.

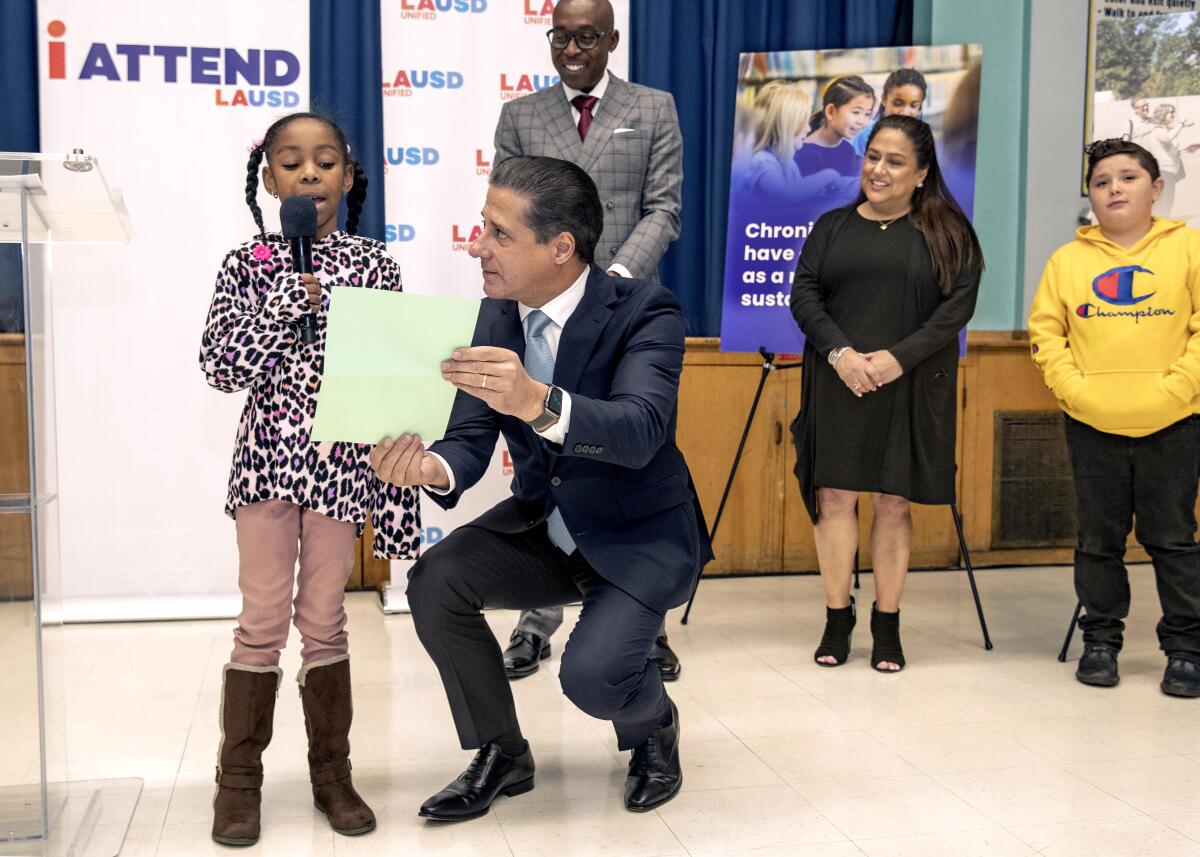

One of his most important tasks is improving academic achievement at the 100 schools that have the highest number of low-income and low-performing students. Carvalho, who often mentions that he lived under a bridge when he was homeless as a teenager, has a soft spot for underprivileged students. Reaching out to these students with personal home visits has become Carvalho’s hallmark in implementing the district’s iAttend program designed to address the district’s chronic absenteeism, which reached 39.8% in the last school year, compared with 30% statewide.

His experiences as a former teacher and an immigrant from Portugal help him understand that a holistic approach is necessary when it comes to helping struggling students. The outreach efforts seem more promising than his “Born to Learn” campaign to recruit newborns in maternity wards. Handing out care packages to babies at hospitals is a good photo op but will do nothing to alleviate the more pressing needs of current students.

Carvalho is ambitious, and that’s a good thing for the leader of this challenging school district. But he should remember that steering the ship is not the only task required to get moving in the right direction. Late last year, he announced that the district would be using artificial intelligence to create acceleration plans for every student, based on data such as math and English proficiency and attendance. These individual reports would create recommended learning strategies that could be powerful tools to help guide students. The program is still in trial mode, and its success this coming year could be the real test of whether he offers more than big ideas and can listen and communicate effectively with teachers and parents.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.