Editorial: Why do state regulators keep failing residents in Exide lead cleanup?

Imagine finding out that your yard, where your kids play and your fruit and vegetables grow, is contaminated with dangerous levels of lead, a powerful, brain-damaging poison with no safe level of exposure.

You wait for years for a slow-moving state bureaucracy to get around to removing soil from your yard riddled with pollution from a nearby lead-acid car battery recycling plant. Cleanup crews finally arrive to excavate and truck it out. But years later, testing confirms they failed to remove all the contamination and unsafe lead concentrations remain and your family is still at risk.

That’s the reality facing numerous families in southeast Los Angeles County, according to a Times investigation into the state-run cleanup of neighborhoods around the shuttered Exide battery recycling plant. Journalists Tony Briscoe, Jessica Garrison and Aida Ylanan reported that the surface soil of dozens of remediated homes, when retested by researchers, had lead concentrations above health standards, and that cleanup contractors failed to meet state soil-removal guidelines at more than 500 of 3,370 cleaned properties.

Once again, state regulators have failed to protect the people of East L.A., Boyle Heights, Maywood, Bell and other nearby communities. For decades residents have paid the price of lax government oversight of the Vernon battery recycler, and more recently, the state’s inability to swiftly and properly clean up the toxic mess it left behind.

A referendum to overturn a ban on new oil drilling near homes and schools qualified for the November 2024 ballot. In the meantime, California should deny requests to drill more oil wells in neighborhoods.

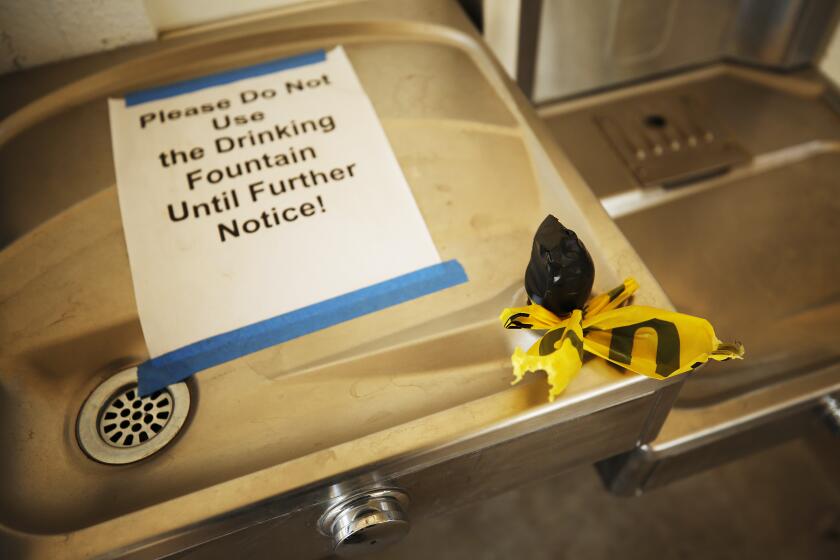

The Times revealed, among other problems, that contractors violated environmental rules, allowed toxic dust emissions to drift into neighboring yards and stored contaminated soil on the same block as a preschool without proper signage to warn the public. The state also has yet to offer a plan to clean thousands of strips of land between people’s yards and the street, known as parkways, years after detecting alarming levels of lead contamination.

It’s infuriating that the state agency leading the largest and most expensive environmental cleanup in state history continues to fall short of its responsibilities. This is an environmental injustice on top of the environmental injustice perpetuated over decades of government negligence that has harmed generations of residents spanning 10,000 properties in the predominantly Latino, working-class neighborhoods surrounding the plant. In greatest danger are young children, who can suffer permanent damage including developmental and behavioral problems and lost IQ points from exposure to even tiny amounts of lead-contaminated soil or dust. A 2016 state analysis found 285 children near the Exide plant with elevated lead levels in their blood and that children living closer to the facility had higher levels than those living farther away.

California regulators bear special responsibility because they allowed the facility to melt down used car batteries for more than three decades with only a temporary permit, even as it racked up environmental violations. Community outrage boiled over in 2013 when air quality officials revealed that more than 100,000 people near the plant faced an increased risk of cancer from its arsenic emissions. The facility shut down permanently in 2015 under the threat of federal criminal prosecution.

Children in many California schools may to exposed to lead in water fountains unless school districts conduct widespread testing and, if needed, clean up.

Residents who fought to close the plant have had to wage another battle to get the state to clean homes, schools, parks and other contaminated properties. The $750-million project is now being funded by taxpayers. Exide, which acquired the plant in 2000, was allowed to abandon the shuttered facility and the cleanup in 2020 under a court-approved bankruptcy plan.

These latest revelations renew long-standing concerns about the state Department of Toxic Substances Control’s ability to manage such a massive project. Soil removal from yards began nearly a decade ago but the department has stumbled at nearly every stage, including needless delays, cost overruns and mismanagement, failures to coordinate with other agencies and to use the data and legal tools available, among other shortcomings that have left children at continued risk of lead poisoning.

DTSC Director Meredith Williams defends her department’s approach to prioritize the cleanup of properties with the highest concentrations of lead, rather than proceeding block by block. But this scattershot pattern has been criticized by community groups and county health officials because it allows recontamination of cleaned properties.

Leaving the daily standard at the same level set 16 years ago would give Americans the false impression that the air they are breathing is safe.

State officials insist the community should feel safer today than before the cleanup. But these latest revelations call those assurances, if not the state’s entire approach to the cleanup, into question. Though the department admits to missteps and pledges to do better, residents have heard that before, only to be disappointed. They are right to be outraged and disgusted.

Gov. Gavin Newsom, state lawmakers and the recently formed Board of Environmental Safety charged with overseeing the Department of Toxic Substances Control need to step in to address the insufficient oversight of cleanup contractors, the scattershot cleanup method, the lack of remediation of parkways and any other problems that could be leaving behind lead pollution or recontaminating these neighborhoods. The state should heed calls from L.A. County supervisors and undergo an audit of the cleanup. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which has been largely absent, should also get involved and designate the Exide cleanup zone a Superfund site, which would allow for additional federal dollars for remediation.

These communities were dumped on for decades, neglected by regulators, and now must contend with the prospect that they may still be at risk in their own homes. They deserve better. It’s long past time for authorities to be held accountable and get to work making things right.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.