Editorial: Don’t leave 211 callers hanging

Los Angeles County supervisors are preparing to turn the operation and management of a key resource information service over to a firm that took on a similar job for the state Employment Development Department early in the pandemic, when business closures and layoffs were rampant — and did it poorly. Deloitte’s EDD phone center left millions of calls unanswered and hundreds of thousands of newly unemployed Californians with no connection to information about their missing payments.

Deloitte’s proposal relies on automation of 211 calls. Even if the consulting firm has worked out whatever kinks led it to mishandle so many state EDD calls, automation may not be the right approach to a service that historically has relied on the human touch for successfully linking callers to services.

211 is a phone line that’s little known to people who don’t need it and an essential lifeline to many who do — the county’s most vulnerable residents, including the elderly, the unemployed, shelter residents and the unhoused.

In L.A. County, 80% of the nearly 400,000 calls came from women and 85% from people of color. A quarter of all callers dialed the number every month, according to a study commissioned by the county of a five-year period concluding in 2017. Anecdotal but unverified evidence suggests that figure remained steady through the pandemic.

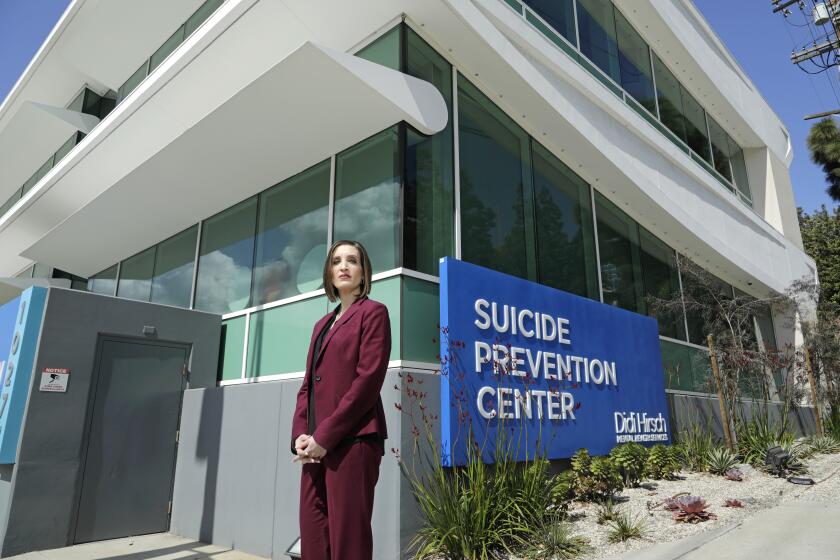

A landmark unarmed crisis response alternative to 911 is about to go online across the U.S. without guarantees of funding to keep it going.

It’s the number that anyone in the United States and much of Canada can call when they are in dire need of food, addiction counseling, child care, financial assistance, housing and other services provided by government and nonprofit organizations (the bulk of referrals are to nongovernmental providers, not to county agencies).

At the other end, in theory, are resource counselors who help explain to callers what services are available to address their urgent problem. For example, “I just got evicted and I have no place to sleep tonight and no idea where there’s a shelter bed available.” Or, “On my way home from work I met a homeless woman who didn’t know where to find a bed for the night and shelter from the rain. Can you tell me how to help her?”

It’s also the way government connects people with help in the event of a disaster, like a hurricane or earthquake, helping victims find immediate shelter, clothing and food, or assisting them when they need to evacuate their neighborhoods or cities.

Unlike 911 and the new 988, 211 operators don’t dispatch on-the-ground emergency responders.

But neither is 211 just a county version of 311, which is a sort of directory assistance for city services such as trash pickup and graffiti removal.

988 may be the better emergency number for people struggling with thoughts of suicide, but a 211 operator, too, can connect callers in need of psychiatric services. Confusing? 211, 911 and 988 callers need not worry whether they’re pushing the right buttons on the phone. The emergency numbers are linked with each other and callers are sent to the most useful resource.

Suicide prevention and crisis response systems need more support.

The current operator of L.A. County’s 211 service is called, appropriately but confusingly, 211 LA. The organization is understandably unhappy about the prospect of losing the contract it has held in one form or another for the last 40 years, first as “Info Line” before 211 went online in California. Although the firm’s leaders acknowledge that its service is far from perfect, they blame underfunding by the county. They say they provide a level of personalized care and expertise that gets people in desperate need the proper resources with a minimum of frustration and wasted time.

The county meanwhile, is looking for efficiencies, and Deloitte offers an automated system that would be familiar to anyone who has called a bank or credit card company with a billing question.

But sometimes you really do need a live human voice and an experienced phone counselor to figure out what you need and what’s available, and to connect you with it. As with many automated systems there would be an option to speak to a representative, but experienced call center operators note that by that point, the call volume often drops off because callers get frustrated. That means lower costs for the contractor — but also potentially less service to callers.

Before finalizing the L.A. County’ new 211 contract, county supervisors should remember the reasons for creating 988, which began operating over the weekend. It’s not merely to have an easier-to-remember suicide hotline, but to respond to people in need with a live human being trained in the particular needs of people in desperate straits.

The desperation for 211 callers may be slightly less urgent, but it is urgent all the same. That’s something for the board to keep in mind when it makes its final decision about who will answer the phone when residents in need call.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.