Editorial: Pay attention to parents’ dissatisfaction with California schools

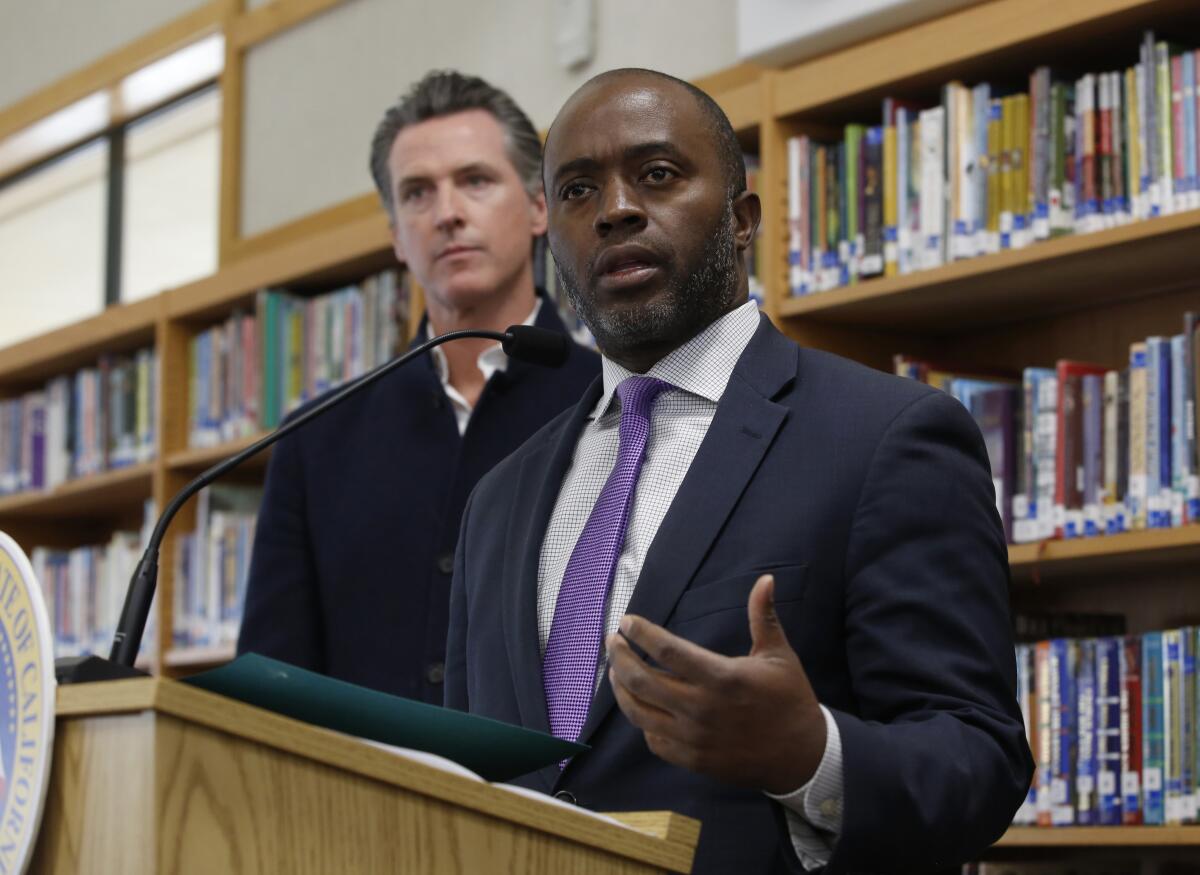

Of course, state Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond was by far the leading vote-getter in his quest to keep his job in the June 7 primary. He had serious money behind him and, in a heavily Democratic state, he was endorsed by the California Democratic Party, both statewide teachers unions and Gov. Gavin Newsom.

And yet, it appears Thurmond was unable to muster the majority vote needed to win outright. Unless the slow mail-in vote count takes a surprising turn as the last few votes are counted, he will have to face the runner-up in November, whomever that might be. Three of the six are in such close contention with one another that it’s too close to call.

Thurmond’s less-than-majority lead going into November should be seen as a reflection of deep dissatisfaction with how the schools are being run. Yes, the superintendent of public instruction is an elected office singularly lacking in actual power. The governor and Legislature set the laws and budget for education, and the state Board of Education interprets those laws into regulation. Most voters don’t know that; they think the state superintendent must be the CEO of schools, much like superintendents of their local schools.

Thurmond has been too low-profile and unwilling to take strong stances. Many of his deputies abandoned ship, citing a toxic workplace. He has a lot to prove if he wants another term.

But that is not the case. In fact, the running of schools at the state level would work better if the superintendent position were done away with altogether. Instead of being led by an elected but unempowered weak official, the state education department should be headed by an appointee of the governor, so that there is a clear alignment of policy and responsibility from the top down. That’s how the state’s public health services are run. But it would take a voter-approved amendment of the state Constitution to do the same for schools.

In the meantime, though, the job exists and it should be performed as well as possible. That has not happened during Thurmond’s first term. California’s students and their parents deserve a more decisive champion.

The role is not without influence. The schools superintendent can use the department’s funding to devise new programs; push hard on lawmakers to make necessary changes on topics as varied as setting academic standards or reforming school discipline; and lobby for a bigger schools budget, for changes to how schools are being run and to the state Education Code. In fact, Thurmond did help push through legislation to create universal transitional kindergarten. The change will help give students a head start, but studies have found that the boost tends to wear off with time. They need an effective K-12 education system to continue the momentum.

Delaine Eastin comes to mind as an example of a strong state superintendent of schools. She held the job from 1995 to 2003, and lobbied successfully for class-size reduction in primary grades and pushed school districts to adopt higher academic standards. Many of them did. She also led the campaign for school gardens, began paving the way for broader access to preschool and developed a financial accountability system for school districts.

Thurmond has been too low-profile and unwilling to take strong stances. Many of his deputies abandoned ship, citing a toxic workplace. He has a lot to prove if he wants another term.

The superintendent is the top administrator of the Department of Education, responsible for ensuring schools’ adherence to the state’s huge and complex education code, hiring and firing staff, and overseeing the annual assessments of school performance. But running the department carried special challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s all the more reason why California students and their schools needed a strong advocate. Schools should have reopened once transmission levels were tamed and vaccines were widely available, but Thurmond never pushed to make that happen.

Districts were looking for clear guidance from the department about how much instructional time was necessary and how it should be conducted. Home or campus? With masks all the time? Indoors or outdoors? Firm guidance wasn’t forthcoming. Meanwhile, parents, who were essentially left with the task of teaching their children while still holding down jobs, were frantic and frustrated.

Thurmond’s track record as a manager is mixed as well. Last year, the department hired his longtime friend as a deputy superintendent, though the man lives in Philadelphia and had no intention of moving here. Thurmond’s management style reportedly prompted nearly two dozen senior officials to leavethe education department, accusing Thurmond of caring more about his image than about making meaningful progress on learning.

Thurmond says he has learned from his mistakes, though he is vague about what he considers those mistakes to be. He touts his new initiative to improve literacy, but so far, and he hasn’t done much more than hold meetings with school superintendents and securing funding allocations to be used in ways that have yet to be well defined.

State lawmakers should heed his poor showing in the primaries. Though Thurmond had all the election advantages of an incumbent, he was hampered by voters’ frustration with the state’s failures to produce well-educated high school graduates, to reopen schools in a timely manner after pandemic closures and to help students recover from the stress and learning loss of the last two years. If he wins reelection in November, as expected, we hope this experience will encourage Thurmond to use a second term to be a better education leader.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.