Op-Ed: Pregnancy is risky. Losing access to abortion puts women’s lives at stake

As the United States struggles with the imminent demise of Roe vs. Wade, politicians and voters need to remember one thing ahead of the midterm elections: Abortion saves women’s lives.

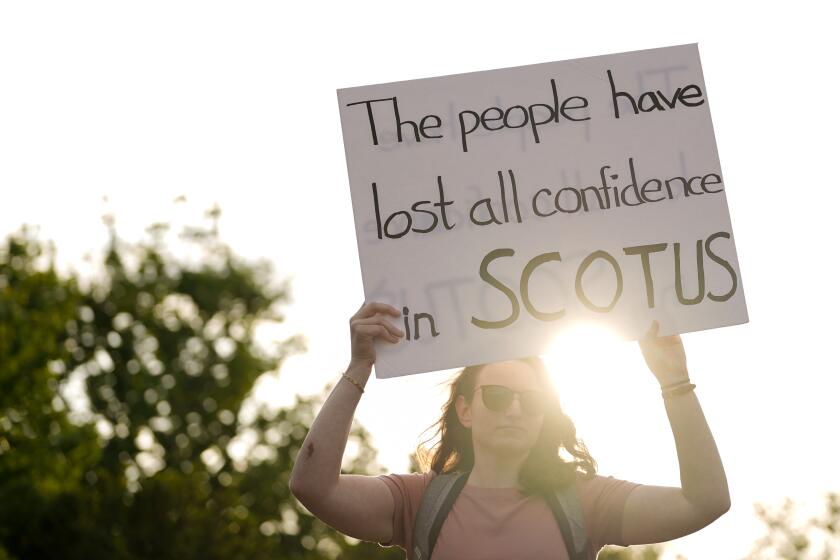

The Supreme Court’s decision, a draft of which was leaked this week, will all but eliminate abortion rights in half of the country by returning the decision over abortion to the states.

When drafting laws to restrict abortion, state lawmakers still often build in an exception that allows for terminating a pregnancy to save the life of the mother. They consider such scenarios, where the mother’s health is in danger, as narrow and unlikely situations. But it turns out, those risks aren’t so exceptional. All pregnancies carry risk.

The conservatives have embarked on a crusade of judicial activism against a raft of precedents, and not just on abortion.

Among high-income countries, the U.S. has the highest rate of maternal mortality — a rate that multiplies 2.5 to 3.5 times for Black women. Scientific and medical research consistently shows that childbirth is far riskier than terminating a pregnancy, particularly for poor and minority women.

It’s access to abortion that has helped reverse such trends. A 2021 study found that legal abortion “substantially improved maternal health for disadvantaged groups,” and that maternal mortality among Black women decreased by 30% to 40% following the legalization of abortion.

Amanda Jean Stevenson, a sociologist at the University of Colorado Boulder, predicts that requiring childbirth would result in an increase in pregnancy-related deaths by 21% — and for non-Hispanic Black people by 33%.

Abortion turns out to be much less likely than pregnancy and childbirth to put a woman’s life at risk.

The introduction of the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol made abortion safer than Tylenol in the first 11 weeks of pregnancy. Medication abortions with these drugs now constitute 60% of abortions that occur at up to 10 weeks’ gestation, which is when the vast majority (88%) of abortions in the U.S. occur. For the 1% or less of people who need abortions at or after 21 weeks of gestation, surgical abortions are also safer than childbirth, and are often the only option to save the life of the pregnant person, or when the fetus is not viable.

Another set of risks comes with the approximately 30% (and possibly up to 50%) of pregnancies that result in miscarriage and stillbirth.

In both low- and high-income countries where abortion is criminalized, women have died when they experienced a medical emergency during a miscarriage. Savita Halappanavar died in Ireland in 2012 after being denied an abortion because fetal cardiac pulses were still detectable, even though she experienced a miscarriage and her gestational sac was protruding from her body. Her experience galvanized the Irish people to repeal the 8th Amendment of Ireland’s constitution and pass legislation decriminalizing abortion. Outlawing abortion makes it more risky, not less common.

American women denied medical treatment in Catholic hospitals while experiencing a miscarriage have undergone severe infections and mental trauma. Others have been charged with manslaughter and murder for experiencing a miscarriage or inducing an abortion.

Here are the basics on the Supreme Court’s upcoming ruling on abortion.

And then there are the host of risks that follow childbirth. Women denied an abortion experience a panoply of negative outcomes physically, mentally and occupationally. This includes diminished physical and mental health, worse economic positions post-childbirth and comparatively worse economic outcomes for existing and subsequent children. Given that the majority of women who seek abortions already have other children, how those existing children fare is also linked to their mother’s own physical and mental health.

Such examples fly in the face of Americans’ widely shared interest in protecting — and saving — pregnant women’s lives, including those who ardently oppose abortion but commonly make exceptions in favor of protecting the mother’s life. In the National Abortion Attitudes Study, which one of us worked on, an interviewee said: “Why would my doctor or anyone tell me to keep my pregnancy if they know I can possibly die at the end?”

As scholars doing comparative, international research, we know that the most important predictor of how well women and children do in terms of health and economic outcomes is family planning and access to contraception and abortion. Equally important, research demonstrates that outlawing abortion does not actually reduce it.

If the proponents of state laws banning abortion, including in Oklahoma, Texas, Kentucky and Mississippi, are motivated by a desire to save women’s lives, then the empirical evidence actually suggests an alternative: We can save women’s lives by making abortion healthcare widely available to all. Now that the Supreme Court seems poised to reduce its protections for women, it is incumbent upon state and congressional lawmakers to ensure that women continue to have access to lifesaving healthcare.

Tamara Kay is a professor of global affairs and sociology at University of Notre Dame. Susan L. Ostermann is an assistant professor of global affairs and political science at University of Notre Dame. Tricia C. Bruce is a sociologist and an affiliate of the Center for the Study of Religion and Society at University of Notre Dame. The views expressed do not reflect those of the authors’ employer.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.