Op-Ed: For my Korean-Black family, the aftermath of the L.A. riots cut deep

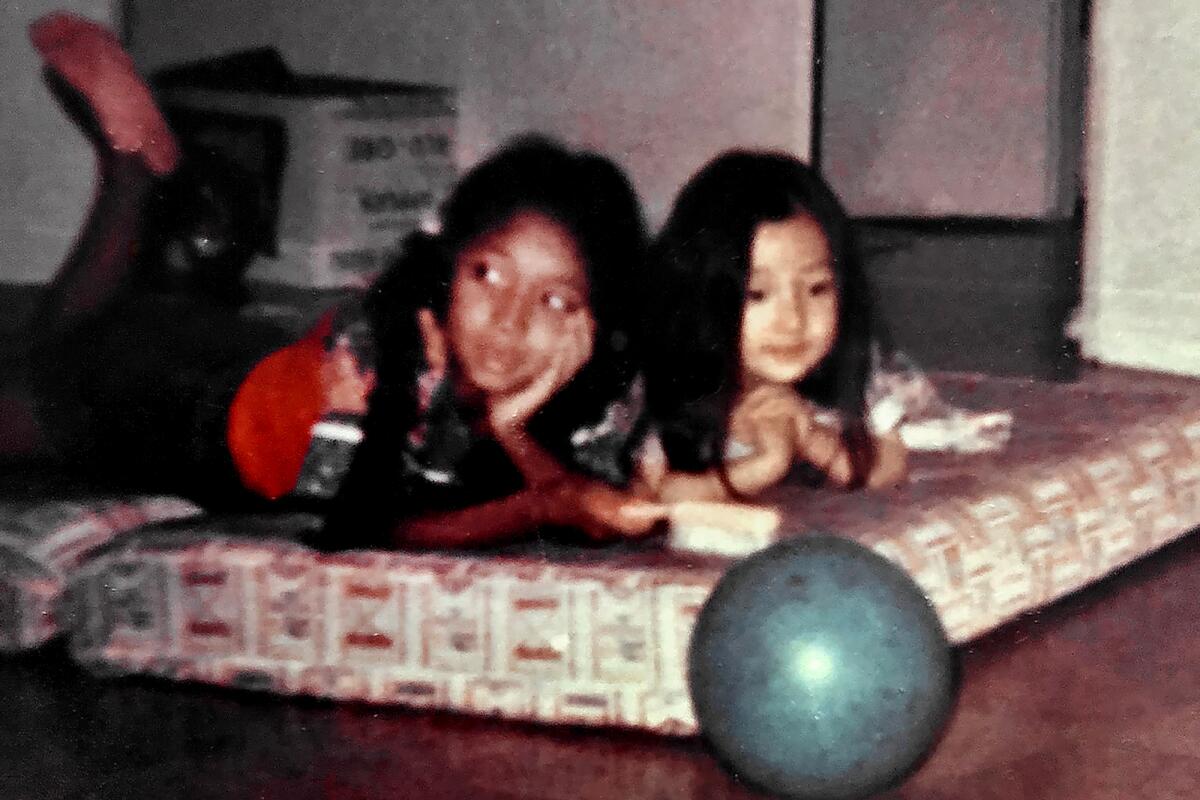

When I was little, I wanted to be Black. Specifically, I yearned to be my older cousin Louise, who was half Black, half Korean and, to me, a complete badass even before I knew what the word meant.

While I was a cautious kid who observed people at length before interacting with them, Louise walked into every room as if expecting something cool to happen. I admired how she skated around her neighborhood, collecting friends while singing pop songs. Whenever she visited my family’s apartment in Koreatown, it felt as if a celebrity had arrived — news of her presence spread quickly among my friends and the energy in the room spiked as we competed for her attention.

By the time the L.A. riots broke out on April 29, 1992, my family had long moved away from K-town, to a Los Angeles suburb 30 miles south. Thirty years later, it’s disconcerting to think about the events leading up to the riots, because they could just as easily happen today: A largely white jury acquitted of assault four police officers — three of them white — who had brutalized Rodney King, an unarmed Black motorist who had led police on a high-speed chase.

A nearby resident had video-recorded the savage beating in March 1991 of King, huddled on the ground as he was attacked. Yet, a year later, the officers walked free. Hours after the verdict, violence erupted throughout L.A.

In Koreatown, angry crowds destroyed businesses, breaking into stores and setting them on fire. Law enforcement did little to quell the pandemonium, so desperate Korean shopkeepers stood on rooftops with guns pointed at the mob below. Tension between Korean and Black residents had already been smoldering because, two weeks after King was beaten, Latasha Harlins, a Black teenager, had been killed over a bottle of orange juice she had slipped in her backpack. The store owner received probation and a fine.

An altercation at Leimert Park liquor store was a reminder that the embers of the 1992 L.A. riots still smolder in communities where economic disparities and racial and cultural misunderstandings never went away.

The civil unrest across the city was wrenching for a family like mine, made up of both Korean and Black members. I was in high school, and I remember watching the TV news at a Korean American friend’s house after classes, horrified as flames swept across familiar streets where my family shopped on weekends. As the footage showed a burning storefront, my friend began wailing: “That’s my parents’ shop!” I was confused about how to feel, whether I should pick a side.

My family hardly spoke with Louise’s during the riots and their immediate aftermath. Instead, we did what we always did, remaining silent and burying our feelings deep. Although we avoided discussing race relations, a chasm was already growing.

In light of the riots, an earlier interaction with Louise took on new meaning. When I was 8 and Louise was about 11, we were dressed like little princesses for a Korean relative’s wedding in L.A. During the reception, Louise burst into tears and ran off. I, her faithful shadow, followed.

In the restroom, I found Louise sobbing.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, befuddled.

“Everyone’s staring at me!”

I gazed at her, so lovely in a pink dress that complimented her complexion. “It’s because you’re pretty.”

“No!” she hollered. “It’s because I’m Black!”

I knew many of the Korean attendees at the wedding, and they seemed perfectly nice. “Are you sure?”

“Hye Yun,” she said, calling me by my Korean name, as everyone in my family did. “You’ll never understand. You’re not me!”

At that moment, I realized that my complete, blanket admiration for Louise had blinded me to what she dealt with every day. I had been captivated by what I imagined her life to be, not by what her life actually was.

Throughout my childhood, my dad was always reminding me that any racism we faced in America was mitigated by the fact that Black people had already endured far worse — they’d suffered and fought for the civil rights that all Americans enjoyed. And that’s why my father, a lifelong Republican, voted for Barack Obama. Twice. His reasoning: We owe Black Americans.

In one victory, L.A. has renamed a playground for the Black teenager who was shot at a South Central liquor store in 1991

By “we,” he meant people of color, and specifically, our family. Our Black relatives had eased my Korean immigrant parents’ early days in America in the mid-’70s, giving them a place to stay, helping them find jobs. Perhaps we wanted to preserve this image of racial harmony by avoiding uncomfortable discussions about the riots, even if it meant missing an opportunity at closeness and understanding. Besides, whenever I looked at Louise, I never saw suffering and sacrifice. I saw only radiance.

And that is my personal takeaway from the L.A. riots — that we have a tendency to rely on our perceptions of what someone’s intentions or life might be, rather than seeking to truly understand. Leading up to the riots, it was an unfortunate but common occurrence that some Korean shopkeepers had (often unfairly) treated their low-income customers as thieves and delinquents. And the customers, in turn, had (often unfairly) treated the shopkeepers as the face of oppression.

The fallout from the riots was complex, and it had a splintering effect on my family — and on Louise and me. The riots created a distance between the two of us, a rift that had already begun forming as I grew more involved in Korean American organizations, and she in her Black community. We hardly spoke while I was in college on the East Coast or after, when I moved abroad. We were still distant when, in 2013, Louise unexpectedly died of a heart condition.

Of course, I foolishly thought we would have more time. I’d imagined that, at some point, we would share a quiet moment. Perhaps our conversation would’ve turned to the L.A. riots and how that violent and turbulent time still echoes today. Maybe we would’ve had several Zoom chats during these pandemic years to share our heartache over the murder of George Floyd, the pervasive hate crimes against Asian Americans, the sad state of race relations in this flawed country we love.

How I wish I could tell her this: “I will never be you, nor will you ever be me, but love is a bridge that can close the gulf between us. Let’s meet halfway.”

Helena Ku Rhee is a Los Angeles author. Her latest children’s book is “Rosa’s Song.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.