Op-Ed: Heartbreak hurts, in part because our cells ‘listen for loneliness’

My curiosity about my leukocytes started before the pandemic. I was motivated by the oldest and most basic grief we experience: the loss of love. But the lessons from my heartache and the emerging neurogenomics of loneliness have much to offer our strange moment in time.

I was late to join the heartbreak club. I met the man who would become my husband when I was 18, on my first day of college. After our 25-year marriage ended in 2017, I was stunned by the pain, by the swiftness with which grief engulfed me. There was so much loss: of the physicality of him; of my sense of self; of my grasp on a predictable, secure future. Then there was the loss of my health. I was shedding weight I didn’t want to lose, barely sleeping, and my pancreas suddenly stopped producing enough insulin. I was tipping into diabetes. My body felt like it was plugged into a faulty electrical socket.

Where was the science? Why was heartbreak so physical? After a million years of hominins sighing at the moon over lost love, what had we figured out?

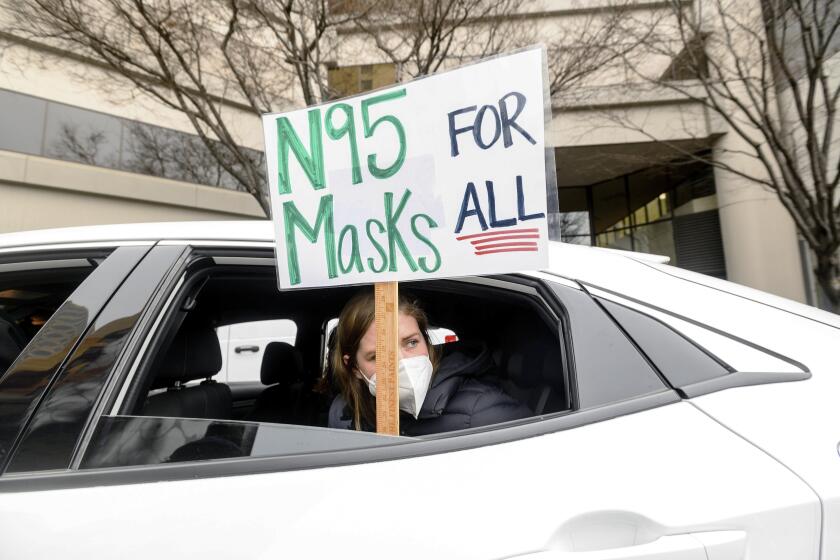

At first, it appeared Omicron might be a “great unifier,” spreading equally through the county, but then it took a turn toward lower-income communities of color.

The rejection piece was one part of it. We humans are very sensitive to social slights both large and small. But the loneliness piece was another, and it’s the one with the lessons I keep coming back to. Although many of us happily embrace solo living — after a divorce, during a pandemic — our ancient nervous systems are not well suited to it.

As we slouch through another month of pandemic and stare down another season of heart-shaped chocolates, it’s worth taking a closer look at the toll loneliness can take.

By now, much is known about the health risks of both being socially isolated and feeling lonely (and it is subjective feeling; it aligns with isolation, but not always). People who identify as one or the other — or both — face higher risks of inflammation-driven diseases like stroke and heart disease, dementia, some cancers and, yes, diabetes. Across studies of many people in many countries, epidemiologists find consistent correlations between social state, disease progression and early death.

Unfortunately for me, they also find a relationship between these diseases and being divorced. “There is an inflammation story related to divorce,” as David Sbarra told me. A psychologist at the University of Arizona, he co-authored a review paper in 2011 that found a 23% increased risk of early death for divorced people compared with married people.

To find out how that was playing out for me, over two years I deposited vials of blood in the lab of Steven Cole, a neurogenomics expert at the UCLA School of Medicine. Did my immune cells, in fact, look like those of a lonely person, and if so, was anything I was trying to do to feel better working?

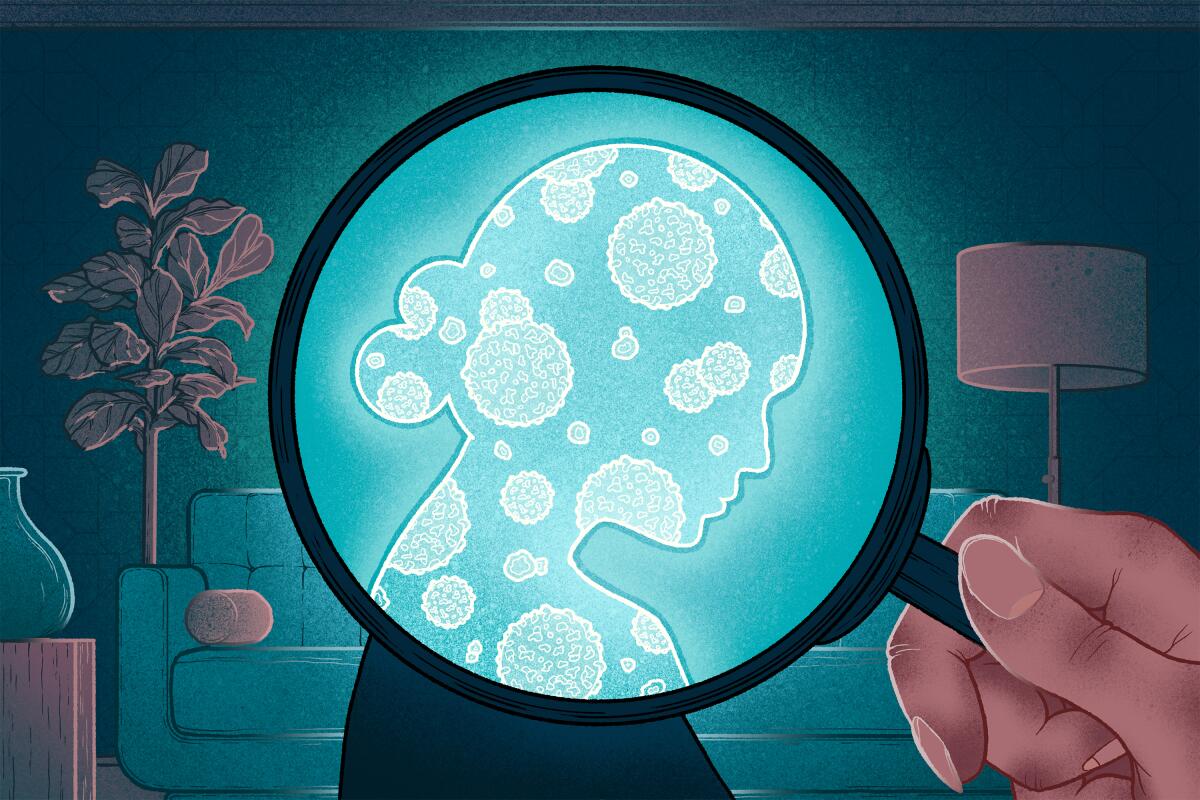

Cole’s interest in how social identity influences health began in 1997, when he and his team discovered that HIV-positive gay men who were closeted suffered quicker immune cell declines and a faster onset of AIDS than those who were out. Somehow their nervous systems, informed by stress-inducing social circumstances beyond just the stress of the diagnosis, were nudging them into sickness. Cole has spent the last 20 years identifying immune-related genes in cells that, in his words, “listen for loneliness.”

Those who are still cautious about the virus are made to feel silly or foolish these days, even as L.A. hits its pandemic peak.

In 2007, Cole and others published a paper finding that generally healthy people with weaker social connections had alterations in a key set of genes governing the behavior of certain leukocytes — white blood cells — that help fight disease. The research provided a strong clue as to why lonely people may face a higher risk of chronic inflammation. Since then, Cole has tried to figure out why social disconnection triggers about 200 genes to brew what he calls “a molecular soup of death.”

Of course, there are a lot of complicating factors facing people living alone. They tend to smoke more and exercise less. They are twice as likely to face poverty as their partnered peers. Experiments with animals who are as naturally sociable as we are can provide cleaner data.

In a study published in December in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine placed 35 pigtailed macaques in isolated housing and 41 in living arrangements of twos or threes. After two months, they infected the animals with simian immunodeficiency virus. Within 14 days, the single macaques showed a 21% higher viral load in their blood, along with 38% and 44% fewer virus-fighting white blood cells — T cells and lymphocytes — than the socially housed animals (the macaques later received antiretroviral drugs).

Why would our immune cells listen for loneliness, in effect making decisions that could make us sick, as well as feeling emotionally rotten after heartbreak or isolation? Our internal defense forces can’t do everything at once, explained Cole. It must take cues from our nervous system — for example, the release of stress hormones when we feel threatened — and determine where to direct its resources.

In our deep evolutionary past, Cole said, being alone meant we were more likely to need to fight bacterial infection from wounds, such as from an attacking predator. At the same time, we were less likely to need to fight viruses that are spread mainly in groups of our own species. How do we best fight bacteria? With inflammation. Unfortunately, this is exactly the wrong call for humans facing HIV, or, Cole added, for that matter, a novel virus. And if isolation or loneliness lasts a long time, so will our heightened inflammation, potentially leading to chronic disease.

“These are inconvenient biological responses to the way we live our life now,” said Cole.

We are vaxxed. We wear masks. And still I’m sitting in a chair in Echo Park listening to my mother cough through the door, knowing we are on our own.

My blood cells after the marital explosion looked pretty inflammatory. Unfortunately, they also looked that way half a year later. This was disappointing because I had been trying very hard to feel better. I’d even spent a month, with friends and on my own, paddling a river in the wilderness. I thought my cells would like that. Maybe some of them did, like the ones in my shoulder muscles. But my leukocytes? Not so much.

How long would it take for me and my cells to feel safer? This and other questions are worth raising, especially in light of recent surges in loneliness driven by pandemic behavior. How quickly do the health effects of loneliness set in? Are they reversible?

Recent studies with animals provide some hope, indicating the health effects of short-term loneliness — weeks or months at a time — are largely reversible. For a study published in July in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Cole and colleagues conducted an experiment designed to mimic pandemic “lockdown.” They placed 21 adult male rhesus macaques in cages by themselves for two weeks. The animals behaved strangely, often lying on the floor. Within 48 hours, they lost 30% to 50% of their virus-fighting white blood cells while ramping up their inflammation-producing ones.

Fortunately, the animals’ immune cells returned to baseline after four weeks of living again in groups. There was more good news. Curious to see whether companionship in lockdown would make a difference, the researchers once again isolated macaques, but added an unrelated juvenile male to their cages (the age differential meant there would be less hostility between them). The adults still lost some anti-viral white blood cells but didn’t make as many pro-inflammatory cells. It’s likely their nervous systems weren’t as freaked out as when they were alone.

John Capitanio, the head of neuroscience and behavior at the California National Primate Research Center, sees clear implications for humans in the research. “Some degree of social connection can really rescue people’s immune systems from the negative effects of being forced to be isolated,” he told me.

My immune cells, too, seem to be looking shinier with the passage of time away from acute heartbreak and loneliness. Although my first two blood draws indicated high levels of genes associated with inflammation, by the third sample, almost two years after the split, those levels were trending down, a good thing. At the same time, it looked like my body was producing a healthier profile of the white blood cells and other factors needed for viral defense.

“You’re looking pretty good,” said Cole. “If it makes you feel better, the leukocytes are on your side.”

It made me feel better.

The monkeys and I were lucky. Chronic loneliness — and disease — hadn’t set in.

His final, ultimately simple, advice to those of us missing love: “Don’t be heartbroken forever.”

Florence Williams is the author of the just-published “Heartbroken: A Personal and Scientific Journey.” Her book “Breasts: A Natural and Unnatural History” won the 2012 Los Angeles Times Book Prize for science and technology.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.