Editorial: When politicians quit early, it leaves voters on the hook

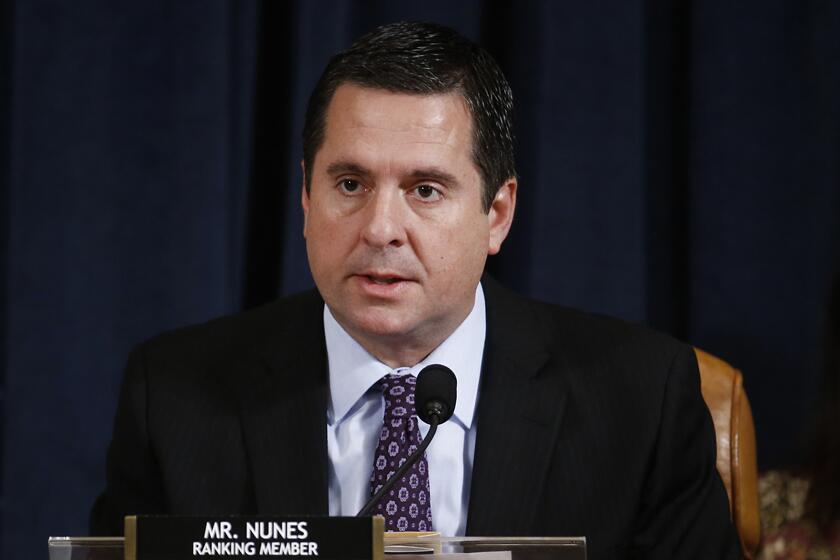

In quitting halfway through his 10th term in Congress to join former President Trump’s social media venture, Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Tulare) leaves his constituents with a parting gift: a round of confusing, costly elections to replace him.

He’s not the only one. Three members of the state Assembly — Ed Chau (D-Arcadia), Jim Frazier (D-Fairfield) and David Chiu (D-San Francisco) — also recently quit halfway through their two-year terms. In all four cases, there will be special elections next year to fill the remainder of the terms that end in late 2022, as well as regularly scheduled elections to fill the following terms. The upshot: Voters in parts of Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area and the Central Valley will face as many as four elections in one year to choose who will represent them in Sacramento or Washington.

On top of that, next year is when new political boundaries kick in following the once-a-decade redistricting routine that balances out representation as the population shifts. That means voters in the current district boundaries will choose a replacement to serve the remainder of the current term, while voters in the new boundaries will elect someone to represent them for the next term. Depending on where a voter lives and how the lines are drawn, some voters will only choose the short-term replacement, some will only choose the long-term replacement, and some will choose both. Different candidates could get elected to each, so a new representative might get sworn into office only to be replaced a few months later.

Confused yet?

Devin Nunes, the thin-skinned dairy farmer known for suing media companies, is quitting Congress to run Trump’s new, yep, social media company.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with more elections. But the low turnout in special elections makes us wonder how well they serve democracy. In the last several special elections for state Legislature in Los Angeles County, fewer than 15% of registered voters bothered to cast a ballot. More voters participate in special elections in other parts of the state — around 20% to 40% — but that is still nowhere close to what’s necessary for a healthy representative government.

Nepotism is another feature of many special elections. Two special elections in the Assembly this year were won by family members of the outgoing officials, with turnout below 30% in each. Mia Bonta (D-Alameda) was elected to replace her husband, Rob Bonta, after Gov. Gavin Newsom appointed him attorney general. Akilah Weber (D-San Diego) was elected to replace her mother, Shirley Weber, after Newsom appointed her secretary of state. Two years earlier, north state voters elected Megan Dahle (R-Bieber) to replace her husband, Brian Dahle, who quit the Assembly to take a seat in the state Senate.

Did we mention the cost? The most recent special election to fill a Los Angeles seat in the Legislature cost taxpayers $2.4 million. Elections in districts that stretch across multiple counties can cost even more.

The obvious way to avoid offseason, low-turnout elections is for politicians to complete the terms they were elected to. Sometimes that’s not practical, because they have health issues or an opportunity to continue serving the public in another office and no control over when it becomes available. Chiu, for example, left the Assembly to become San Francisco city attorney, and Chau left to become a Los Angeles Superior Court judge. Other times, politicians presumably have more leeway about when they quit. Frazier, a former chair of the transportation committee, is resigning from the Assembly at the end of the month to seek “new opportunities in the field of transportation,” he said.

If they — and Nunes — had waited a few months and instead resigned in March, the special elections could have been avoided. But the law requires an election be held if a lawmaker quits before the deadline for candidates to file for the next election.

California voters this year were again faced with a slew of special elections to fill vacant seats in the Legislature.

Ideally, voters and lawmakers would embrace a new system to reduce the frequency of special elections. That could be accomplished by extending the time an office can remain vacant, or allowing a legislative seat to be filled by appointment, as half the states do. The appointment would not have to be made by the governor — it could be made by a leader from the same house and same party, to retain the Legislature’s role as a check on the governor. Another option would be to allow the appointment of a short-term caretaker who would be prohibited from running for the full term. (Such changes could only apply to legislative seats, as federal law does not allow appointments to the House of Representatives. But they would have great impact, as midterm resignations are more common in the Legislature than in Congress.)

Realistically, none of these changes are likely to happen soon. The Legislature, or someone with enough money to circulate a successful petition, would have to put a measure on the ballot — and then voters would have to approve it.

The best solution in the meantime is for voters to show up for special elections so that their representatives know who’s in charge. The outcomes shape environmental, criminal justice and other policies crafted in the state Capitol. That’s why special interest groups pour so much money into the special elections that many voters ignore.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.