Editorial: Academic and emotional setbacks: The LAUSD kids are not all right

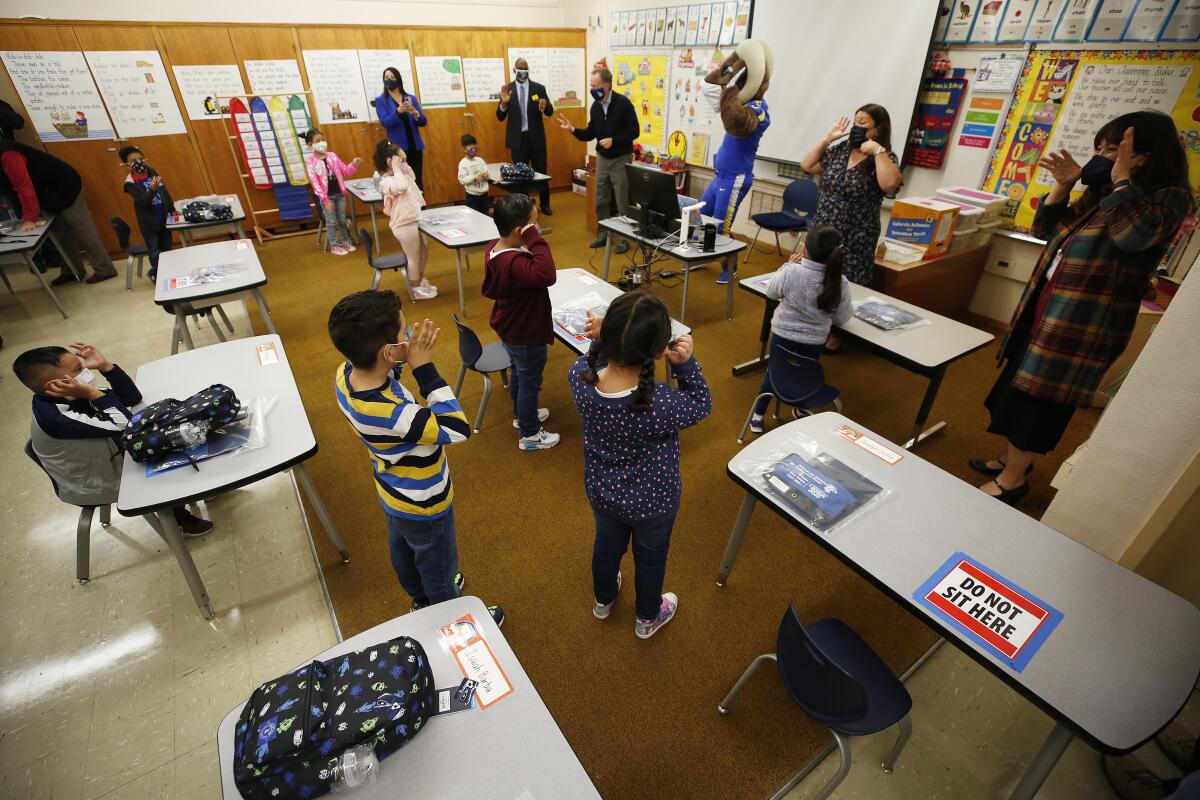

The data are in and they confirm what parents and educators had feared: Los Angeles-area students have slipped academically from pre-pandemic levels, which weren’t good, either. And a disproportionate amount of that loss has been among Black and Latino students whose classroom skills already lagged behind those of white and Asian students.

A Times analysis of student assessment results from the Los Angeles Unified School District showed, among other things, that elementary school reading scores dropped overall by 7 percentage points, and even more for Black and Latino students. The gap between those groups and their white and Asian classmates is now 26 percentage points or more.

Grades dropped dramatically — but only for Black and Latino students. The latter group makes up 81% of the district population, which makes this a districtwide problem. And about 70% of Black and Latino students are reading at below grade level, while the majority of white and Asian students are at or above grade level.

As discouraging as the figures are, it isn’t time to panic. In the short term, there are ways to start building knowledge and skills in students better than they were before the pandemic, and the district is already moving in that direction. There’s reason to think the schools are making inroads, especially with the district’s program providing individualized instruction with specialized teachers in primary grades. But the reading problems obviously extend well beyond those grades.

Right now, the best the district can do to help both students and teachers is to provide focused, high-intensity tutoring by qualified instructors, which it’s already in the process of doing. The effectiveness of this kind of tutoring is well proved; it also takes some of the burden off classroom teachers. The district has allocated $45 million for this tutoring so far but is unable to say how many students are receiving the help because the decisions are made by the individual schools.

It’s true that principals and teachers are best able to make those decisions, but this ignorance at the district level is unacceptable. Given the level of need at schools, the district should be getting a firm handle by now on how many students are receiving tutoring and whether it’s sufficient.

As important as it is to surround students with help, this also is not time to worry that the academic skies are falling. It will take time to bring students back to where they were, though the district must go beyond that. Black and Latino kids especially should have been getting far more in the way of services, such as counseling, preschool and tutoring, before the pandemic. The money wasn’t available. Now it is, and there’s no excuse.

An even bigger issue that the district must address is that schools report large numbers of students struggling with emotional problems, whether it’s social estrangement from the many months shut indoors, general fears about the pandemic or the state of the world, trauma from seeing loved ones die or be seriously sickened, or a lack of structure from the shortened instructional day. This has lead to behavior issues include acting up in the classroom, surging absenteeism and difficulty playing or making friends.

Even more key than drilling long division or algebra at the moment is an emphasis on mental health and social comfort. If California wants an educated and robust population, it must invest in emotional stability and well-being.

But while everyone is paying lip service to children’s mental health, the state is doing relatively little about it. Leaders are worried — rightly enough — about a shortage of teachers, but they should be equally concerned about the lack of qualified therapists for kids’ psychological needs. An August report on COVID-19 and children’s mental health by the Little Hoover Commission notes that in 2018, well before the pandemic, California ranked 48th in the nation when it came to providing mental health services to children.

The state’s approach to mental health for kids is fragmented, disorganized and ever-shifting rather than targeted on the most successful models, the report said. It also has a real shortage of therapists and other mental health workers who specialize in children and needs to adopt policies to increase their numbers, much as it would do to get more people to become teachers.

California no longer can ignore the fact that a well-organized, well-staffed mental health system for children is not a luxury but as necessary as reading and writing. L.A. Unified has the academic work under way, but state leaders should heed the advice of the Little Hoover Commission and fashion a more effective strategy for addressing the emotional well-being of our children.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.