Op-Ed: Why government has a constitutional duty to save the news industry

Only one private institution is mentioned in the Constitution: the press. Our nation’s founders recognized that a press free to criticize those in power and spread information across society is essential in democracy. But what does that mean today when we see newspapers disappearing every month? Is our government failing to meet its duty to protect and strengthen the press?

The 1st Amendment assumes the existence and durability of a private news industry. This suggests the Constitution not only allows but requires the government to take steps to keep the press viable. And in fact, the government has done this since the beginning of the republic.

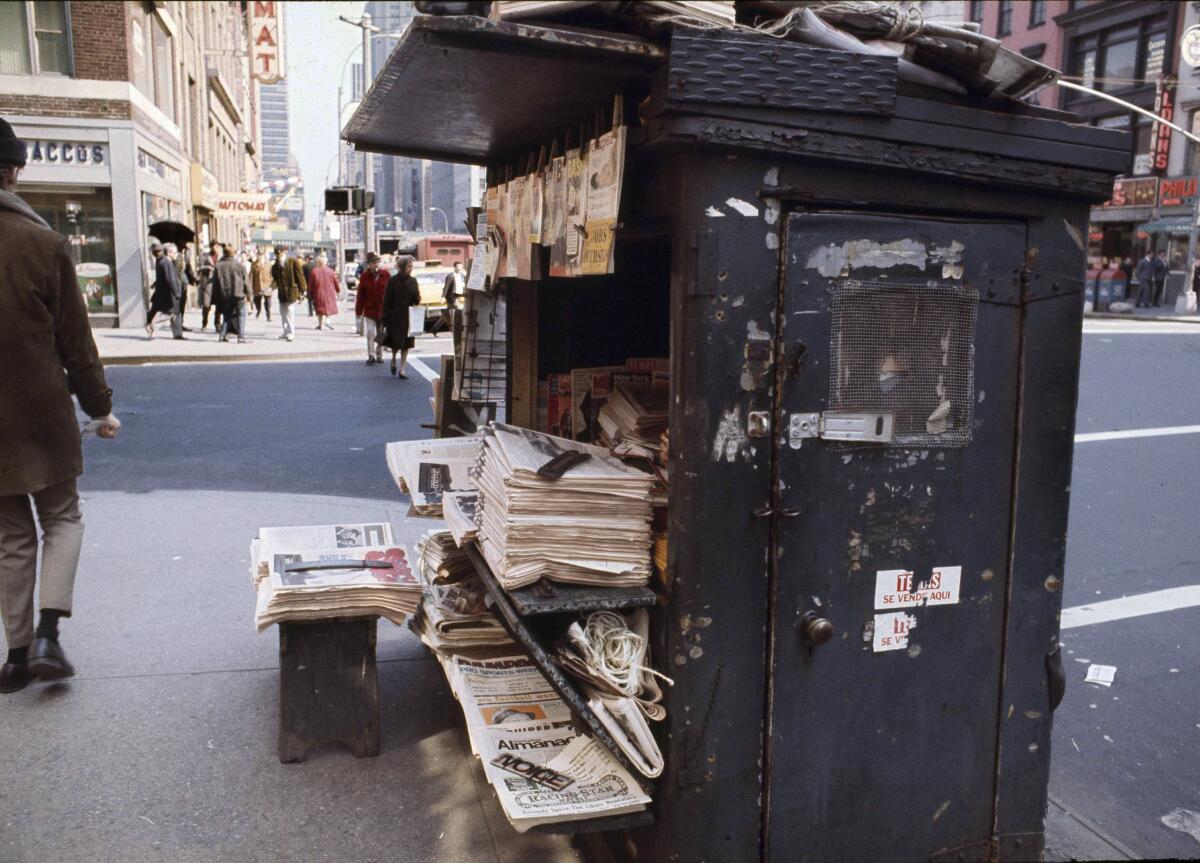

The current press landscape demands new action. Journalism jobs over the past two decades have declined by 60%. As newspapers close and local broadcasting and cable news reduce investment in reporting, digital platforms have diverted ad revenues and enabled the spread of conspiracy theories and misinformation. Especially notable is the loss of reporting in smaller towns, suburbs and rural areas, leaving thousands of American communities with no local coverage. This decline may even be tied to fewer candidates for office in local elections.

The idea of government intervention in the news media is not new. Throughout our nation’s history, the federal government has directly and indirectly contributed to the cultivation and growth of the news industry.

Deliberate government actions map neatly to the history of news in America. The Postal Act of 1792 generously subsidized the delivery of all newspapers. Other policies include investments in the telegraph, regulation of broadcasting and cable, even the financing of research behind the internet. And the government created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, PBS and National Public Radio and developed public television and radio stations, providing critical vehicles for further innovation.

More recently, existing tax benefits for individuals and foundations are helping to strengthen the burgeoning field of nonprofit journalism. The Internal Revenue Service’s 2019 ruling that allowed the 150-year-old Salt Lake Tribune to turn itself into a nonprofit enterprise creates a new model for other newspapers interested in finding a way forward that includes philanthropy.

There are many other ways the government can strengthen the failing news industry while steering clear of censorship or control of media content.

For example, the Local Journalism Sustainability Act, a bill that has bipartisan support in Congress, creates tax incentives to encourage people to subscribe and donate to their local news organizations. It would relieve local news organizations of paying payroll taxes for journalists. And it would also provide tax incentives to businesses that advertise in local news organizations. This could help restore some of the revenue lost in the shift of billions of dollars in advertising to Facebook and Google and other online platforms — none of which has its own newsgathering operation.

Legislation has also been proposed that would address the harms caused by social media platforms in fueling the spread of misinformation and increasing political polarization through algorithms. More people today get their news from social media than from organizations that report and produce the news.

Through antitrust investigations and litigation, government could curb online platforms that abuse concentrated economic power and fail to pay for material generated by news organizations. Congress could end protections granted to those platforms against liability for consumer protection, fraud and defamation — which give them a huge advantage over conventional publishers and media organizations. Federal and state governments could further increase public subsidies for nonprofit and public media and even exempt local news organizations from sales and property taxes.

Such efforts are compatible with the 1st Amendment because they increase, rather than abridge, freedom of speech and press, and because they echo government actions long underway. The amendment’s meanings have also unfolded in response to new challenges. Over the course of the 20th century, its enforcement by the courts came to reflect social changes and demands. Freedom of speech now is a basic, enforceable right, and includes the rights of listeners.

Finally, the large degree of existing government involvement in media, in combination with media’s importance to democracy, lends constitutional support for new policies. Since the 1930s, the federal government has required disclosure by broadcasters of the actual sponsors of materials, because “listeners are entitled to know by whom they are being persuaded.” It has long enforced rules against broadcasters spreading hoaxes. And in 1994, the Supreme Court upheld a federal law requiring cable networks to carry local and public educational stations in service of competition, information dissemination and programming variety.

Voters and government officials — anyone devoted to the Constitution — should not be willing to watch the news industry collapse. Preserving democracy calls for measures to revitalize the creation, production and distribution of news. Any contrary view of what the Constitution permits in this field imperils the very system of government it establishes.

Martha Minow, a professor and former dean of Harvard Law School, is the author of “Saving the News: Why the Constitution Calls for Government Action to Preserve Freedom of Speech.” Newton Minow served as chair of the Federal Communications Commission under President Kennedy.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.