Opinion: Bishops vs. Biden: high drama, low stakes

On Sept. 12, 1960, John F. Kennedy, who later that year would become the first Roman Catholic to be elected president of the United States, said this to an audience of Protestant ministers in Houston:

“I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute — where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote.”

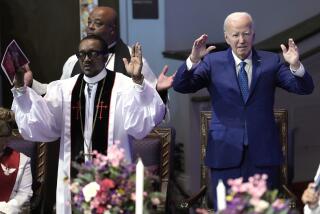

More than six decades later, some Catholic bishops seem to want to tell Joe Biden, America’s second Catholic president, that if he doesn’t act as they wish — by changing his support for legal abortion — he should refrain from taking Holy Communion. That would cut Biden off from a sacrament the Catechism of the Catholic Church describes as “the source and summit of the Christian life.”

Last week the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops authorized the drafting of a “statement on the meaning of the Eucharist in the life of the church.”

That may seem like a purely theological exercise, but earlier this month America magazine, a Jesuit publication, reported that a draft proposal circulated among the bishops indicated that the statement would “include the theological foundation for the church’s discipline concerning the reception of Holy Communion and a special call for those Catholics who are cultural, political or parochial leaders to witness to the faith.”

That sounded as if the bishops were planning on a rebuke of Biden and other Catholic politicians who support abortion rights. The Vatican was concerned enough about where the bishops were heading that in May, a senior cardinal wrote to Archbishop Jose Gomez of Los Angeles, the president of the bishops’ conference, to advise caution.

The Vatican’s intervention may have had some effect. Bishop Kevin Rhoades of Indiana, the chairman of the conference’s doctrine committee, said that the eventual document wouldn’t mention Biden or other individuals by name. Cardinal Sean O’Malley, the archbishop of Boston, wrote on his blog that, in light of instructions from Rome, the doctrine committee had “adjusted” its mission “to avoid focusing on categories of individuals.”

However it ends, this initiative by the bishops is proving divisive within the church and is likely to inflame criticism of the hierarchy in the broader society. But there’s some good news: Even if the bishops were collectively to say that Biden should be denied Communion, there would be little danger of a backlash against Biden or an upsurge in anti-Catholicism.

When JFK was seeking the presidency, anti-Catholicism was a potent force. Many American Protestants worried that a Catholic president would be taking orders from the pope. This was the specter Kennedy sought to exorcise in his speech to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association.

But in 2021, Catholics are thoroughly integrated in U.S. political life. Not only is the president a Catholic; so are the speaker of the House, the chief justice of the United States and the governors of states as different as New York and Texas. Anti-Catholicism has ebbed.

Moreover, it’s hard to conjure up a Catholic conspiracy to manipulate the president when Catholics are divided on myriad issues, including whether Catholic politicians who support abortion rights should be denied Holy Communion.

Last and most important, it’s hard to believe that anyone would expect Biden to change his views about public policy because of an episcopal rebuke.

In 2019, Biden reacted with equanimity after a priest in South Carolina alerted the media that he had refused to give Communion to Biden. Biden could be confident that he would be welcome to take the sacrament in other places. One of those is the Archdiocese of Washington, where Cardinal Wilton Gregory has made clear that Biden is welcome to receive Communion at churches there.

America isn’t the same country it was in 1960, and the U.S. Catholic Church isn’t the same church.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.