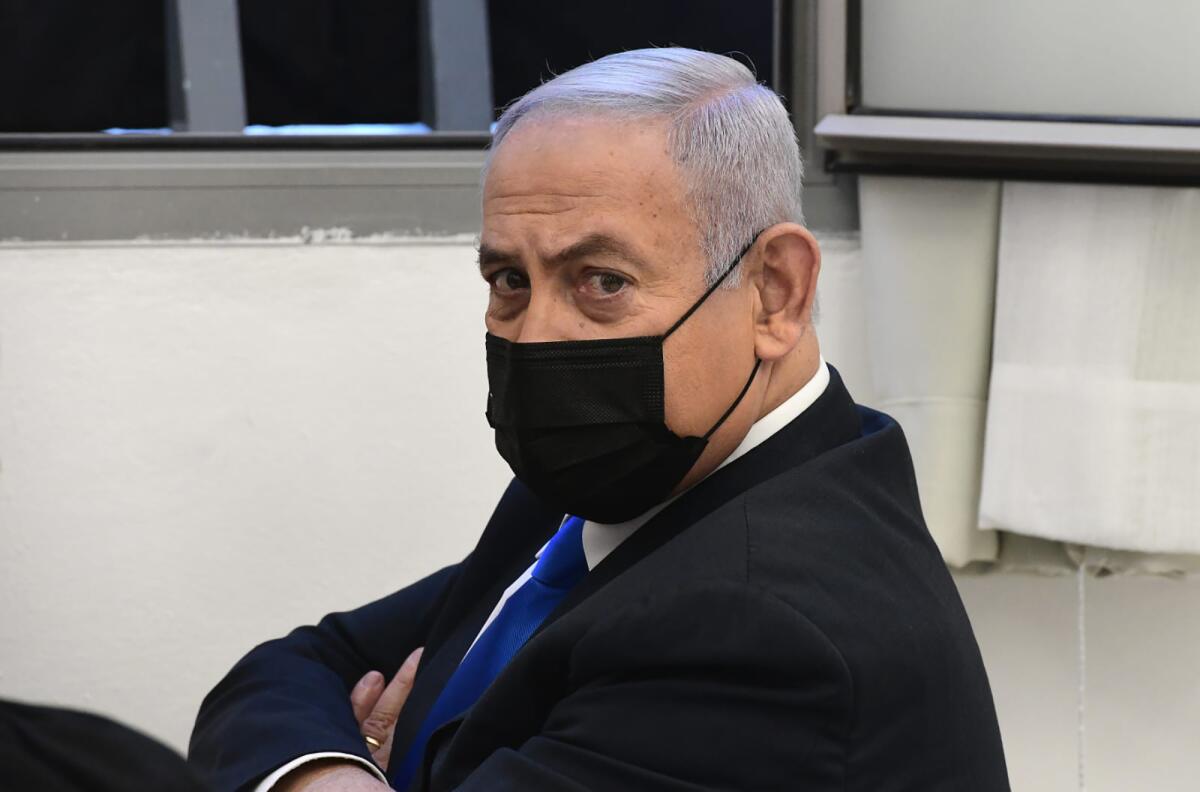

Column: Israel is trying to oust Bibi Netanyahu. But will he really go?

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s political obituary has been written and rewritten.

Each time he fails to win an election or his government collapses, or he is accused of corruption, or, worse yet, indicted, new predictions of his political demise are circulated — only to be superseded, days or weeks later, by the story of his resurrection.

This time, though, his position is especially dire: On Wednesday, his rivals Naftali Bennett and Yair Lapid announced they had pulled together a broad governing coalition in the Israeli parliament that would include parties from the left to the center to the hard right, while excluding Netanyahu’s conservative Likud party. If the coalition receives a vote of confidence from the full parliament, as is expected, Netanyahu will have to step down as prime minister.

So is this the end of the road for the man who has been the dominant Israeli political figure of his era? Is this the beginning of a sharp change in direction for Israel?

My advice? Don’t bet the house on it. And don’t count him out until you hear the prison doors clang shut behind him.

I mean, it certainly would be satisfying to see Netanyahu slink off into retirement and obscurity. Under his stewardship, Israel has grown increasingly illiberal and isolated. He has continued the unjust occupation of Palestinian territories seized in 1967 and has empowered the settler movement in the West Bank and East Jerusalem — so that Israel is increasingly seen as an obstinate violator of international law. His harsh policies have alienated many steadfast supporters and strained relations with the United States. Thanks in part (though not exclusively) to Netanyahu, the peace process is at a standstill and the idea of a two-state solution to the conflict with the Palestinians is on life support.

If Netanyahu is replaced, you won’t hear any complaints from me.

But he’s not gone until he’s gone, as Yogi Berra might say. The reality is that the new coalition has not yet been ratified by the Knesset, and, if and when it is, it will be, for obvious reasons, highly unstable. Keeping so many ideologically diverse coalition partners satisfied while failing to deliver what any of them really want is a difficult balancing act, especially in a volatile country that has held four inconclusive elections in two years. The parties in the proposed new government, frankly, agree on very little.

Only a few defections would be needed for the coalition to collapse. And don’t forget — Netanyahu, who is now 71, will not be out of politics; he’ll have been relegated to the opposition, where he and his Likud party will be scheming and maneuvering for their return to power.

“It’s hard to believe that this new coalition will not crater eventually,” said Aaron David Miller, who advised six secretaries of state over 15 years on Israeli-Palestinian issues. “And Netanyahu will be waiting.”

If the coalition does manage to hold together for a while, it is expected to do so by ducking and dodging the difficult questions that divide its members — chief among them the future of the occupation and the fate of the Palestinians in Gaza, the West Bank, East Jerusalem and within Israel itself. Instead it will focus on issues such as the economy and COVID-19.

Palestinians shouldn’t expect much change for the better if Netanyahu is ousted. Remember who is the kingmaker here: Naftali Bennett, a former settler leader who leads a small right-wing party. He opposes a Palestinian state and wants to annex significant chunks of the West Bank. He’s to the right of Netanyahu.

Under the coalition deal, Bennett would serve as the next prime minister. Of course, he’d be held in check to some degree by his coalition partners. Significantly, he would rotate the prime minister’s job after two years with Yair Lapid, a former TV news anchor who is the centrist leader of Israel’s main opposition party. Lapid’s party controls many more votes than Bennett’s.

But still, a meaningful shift in policy with regard to the peace process and the occupied territories seems unlikely under this coalition.

On the Palestinian side, parliamentary elections were recently canceled. Frustration is growing. In the West Bank, the governing Palestinian Authority is unpopular and perceived as corrupt. In Gaza, which is under the control of Hamas, last month’s fighting with Israel left hundreds dead, destroyed mosques and apartment buildings, damaged schools, hospitals and other infrastructure, and cut off electricity and water to much of the population.

All in all, not terribly propitious for the future.

Netanyahu held on to power far longer than expected, finally surpassing David Ben-Gurion’s record as Israel’s longest-serving prime minister. In recent years, Israeli commentators repeatedly compared him to Donald Trump, partly because of his apparent view that “I alone can fix it.” Like Trump, Netanyahu has a driving desire to stay in power by almost any means necessary, and is disrespectful of the rule of law, the media and political norms.

He honestly seems to believe that his petty corruptions don’t matter because he’s on a messianic mission to save his country. During an official interview as part of Netanyahu’s corruption case, Israeli businessman and movie producer Arnon Milchan recalled something Netanyahu had once told him. “If I fall, the nation falls,” the prime minister said.

Israelis have every reason to try to move beyond a man like that.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.