Opinion: So the union lost to Amazon in Alabama. That doesn’t mean the fight is over

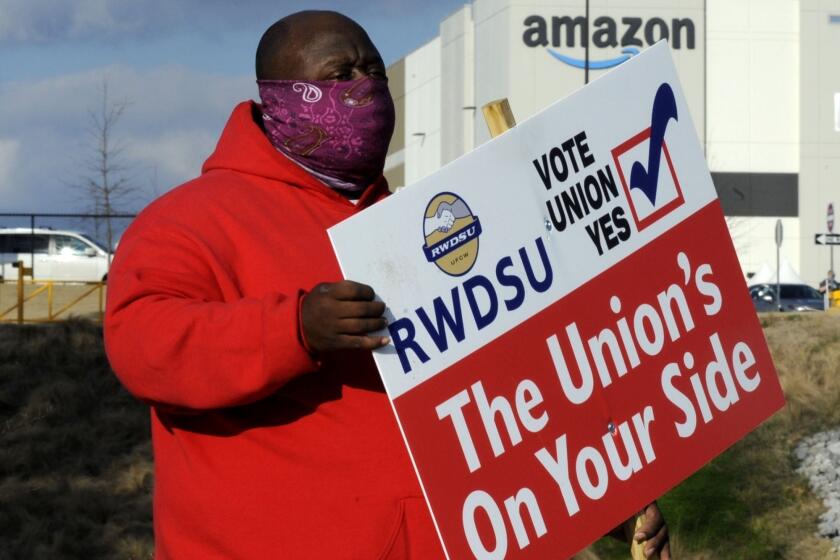

Well, it was a valiant effort, that drive to organize workers at an Amazon facility in Bessemer, Ala., which resulted in a defeat even more embarrassing than the vote count suggests.

Nearly 6,000 workers would have been covered by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, but only a little more than half of the eligible workers bothered to vote. Of those who cast ballots, only 738 workers supported the union, 1,000 votes fewer than those who opposed.

Another 500 ballots weren’t counted after being challenged (mostly by management), but even if you add all of those to the “yes” side (highly unlikely), that would mean a maximum of 20% of the workers voted to unionize, and the percentage in reality is probably much lower.

Ouch.

My colleague Nicholas Goldberg wrote about the Amazon vote against the historical backdrop of union organizing, so I won’t belabor that history here. The deck has been stacked against unions for decades through federal laws, state right-to-work standards and questionable legal decisions, among other factors.

Union organizers had hoped that a victory against Amazon would lead to a reversal of the long, slow decline of the labor movement.

But the biggest problem unions face is they have lost the public relations battle. Remarkably, two-thirds of Americans tell pollsters they support unions. Yet, only a sliver of American workers belong to one, and as we just saw in Alabama, the chief hurdle is unions’ failure to persuade individual workers that being in a union is better for them than not being in a union.

Oddly, nearly half of non-unionized workers say they would join a union if they had a chance, but what people tell pollsters and what people actually do are often two different things.

The reasons are myriad, some of them class-based. I worked at the Detroit News in the mid-1990s when it and the Detroit Free Press went out on strike (a long and violent affair; I left Detroit and the strike after 18 months on the picket line), and I recall some of my fellow union journalists expressing unease at walking a picket line with Teamsters, even though we were fighting the same fight against the same owners.

As the nation has moved from a manufacturing economy to a service economy, more and more jobs are white collar. And while office workers are just as susceptible to worksite abuse, pay inequities, job insecurity and the other issues that unions help counter, they tend not to see themselves as the sorts of people who belong to a union.

Anecdotally, over the years I’ve heard people dismiss unionism because they think they would have to cede control of their work life to union bureaucrats, or that unions are corrupt (I wonder if anyone has done a scorecard of corporate illegality compared with union corruption), or that they don’t need a union because they can negotiate fine on their own.

But that misses the improvement in healthcare and other benefit packages unions have more power to effect (for the community at large, too), established grievance procedures in case a worker gets targeted by a boss, job security and a set formula for determining both the order of layoffs when they are necessary and the severance package when they occur.

The organizing drive in Alabama may in the end prove to have been a one-off. It gathered a lot of attention — including strange political bedfellow Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) — in part because the target was Amazon, not the most popular of businesses in the country. But the campaign was a longshot from the get-go — another reason it attracted so much attention (we love a good David and Goliath story, until Goliath wins).

This is what is normal in the United States: daily gun violence, daily carnage, daily indifference.

The Deep South has historically been difficult to organize, and despite persistent stories about sometimes deplorable working conditions in some Amazon facilities, the wages in Bessemer exceed the mandated minimum, and working conditions clearly weren’t perceived by Bessemer workers to be sufficiently bad to band together and demand changes.

While the drive failed in Bessemer, that does not mean similar drives will fall short elsewhere. I’m sure union officials will be digesting the organizing plan and the results and figuring out how to do it better next time.

But that sidesteps the biggest issue. American unions not only have to persuade American workers that they are relevant, but they have to bring home the truth that they are vital, and that a key step to restoring the American middle class is to restore unions’ role in gaining for workers a bigger share of the spoils of their own labor.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.