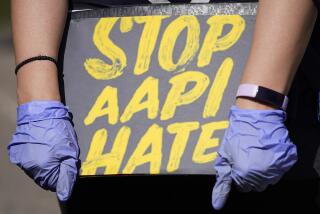

Editorial: Anti-Asian hate demands a societal response

Horrific attacks against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have prompted marches and rallies nationwide, criminal prosecutions and now a response from the White House. On Tuesday the Biden administration announced the revival of the White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, new funding for Asian American survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault, and a renewed commitment to improve health outcomes for Pacific Islanders. Importantly, the announcement includes improved Justice Department enforcement, data collection and transparency around hate crimes; information on the federal hate crimes website will now be provided in Chinese, Korean, Tagalog and Vietnamese.

These steps are certainly welcome, and yet much more will be needed, as the scope of the bias and xenophobia routinely faced by Asian Americans comes into closer view.

Ten percent of Asian American and Pacific Islander adults have experienced hate crimes or hate incidents this year, according to survey results released Tuesday by Survey Monkey and AAPI Data, a repository of demographic information and policy research. Conducted online March 18-25, the survey also revealed that more than one-quarter of Asian Americans report having been victims of such crimes at some point in their lives. Asian Americans normally report lower levels of hate crimes than Black Americans, but this year the two groups are on par.

The survey also confirmed the microaggressions that Asian Americans routinely face: being asked where they are from, with the assumption that they are foreign-born; being encouraged to Americanize or “whiten” their names; having their names intentionally mispronounced; and even being spit or coughed upon.

That last form of abuse is telling, as the recent wave of attacks has been linked to the xenophobia stirred up by former President Trump early on in the COVID-19 crisis. His use of hate-inducing, finger-pointing language like “the China virus” and “kung flu” — without bothering to distinguish between the policies of the Chinese government and the innocent lives of Asian Americans, many of whom aren’t even of Chinese descent — stirred up this ugly surge.

But the anti-Asian bias has endured even with Trump gone from Twitter and the White House. In New York City alone this week, footage emerged first of an Asian American man beaten and choked on a subway train, then of a 65-year-old Filipino American churchgoer kicked repeatedly in the head and upper body in front of a residential building, whose staff did nothing. Both episodes are being investigated as hate crimes.

It is but the latest iteration of a pattern of xenophobia rooted in the American past: the massacres of Chinese in Los Angeles in 1871 and Rock Springs, Wyo., in 1885; the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II; the scapegoating of Muslims and South Asians after 9/11.

This is a pivotal moment for Asian Americans, many of whom only began identifying as such as a result of the civil rights activism of the 1960s. Not since the 1982 killing of Vincent Chin — a 27-year-old Chinese American man attacked by two Detroit autoworkers who believed he was Japanese and were enraged about the economic pressures on American carmakers — have so many Asian Americans felt outraged and galvanized by hate crimes. Many worry that when the media attention subsides, so will the political urgency around confronting the causes of hate.

The sad fact is that Asian Americans, no matter their service to or achievements in America, are still too often seen as foreigners who don’t fully belong in the United States. Their names, languages and cultures are mocked, and their humanity, distinctiveness and dignity are denied. Violent attacks by complete strangers, and the degradation of being spit or coughed on, are the tragic consequences of a long-standing failure of American society to recognize Asian Americans as individuals, worthy of respect and consideration just like everyone else.

Beyond what President Biden announced Tuesday, there are many other steps the federal and state governments should consider, including victims’ compensation funds, better tracking of anti-Asian crimes, more language resources on 211 and 311 hotlines and improved police-community relations. Perhaps, if the pandemic eases, so will the surge of attacks. But the larger sickness is societal.

This month, Asian artists were recognized in Oscar nominations like never before, and fuller, richer storytelling about the tremendous diversity of Asian experiences in the United States is long overdue. But until American society more thoroughly confronts and overcomes its long history of anti-Asian hate, the attacks are likely to continue.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.