Column: What should happen to racist, sexist and homophobic movies from an earlier era?

Given today’s long overdue focus on systemic racism — and the raging culture wars that awareness has engendered — it’s reasonable to wonder what the future will be (and should be) for storied but politically offensive movies like “Gone With the Wind,” “The Searchers,” “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers” and “The Jazz Singer.”

These are just a handful among the hundreds — maybe thousands — of old Hollywood films with scenes, themes and language ranging from highly objectionable to abhorrent. The romanticization of slavery in “Gone With the Wind,” one of history’s most successful and beloved movies, is truly shocking when watched today — but so is the less familiar image of Al Jolson falling to his knees in blackface in “The Jazz Singer” and the insidiously cheerful musical sexism of 1954’s “Seven Brides.”

For years the battle over such films has been between those who want these sorts of bigoted movies retired and deplatformed, and those who dismiss such ideas as “cancel culture” and prefer the world to go on as it always has.

Sometimes it feels like middle ground is hard to find between these warring factions. But I was cheered recently to see that Turner Classic Movies had chosen a thoughtful third way for dealing with what it called “problematic” or “troubling” old movies in a series called “Reframed,” which began March 4 and has its final episode Thursday.

Rather than burying racist, sexist, homophobic or otherwise offensive films in some basement vault and pretending they never were made, TCM instead picked 18 movies — including the ones above — and aired them over a four-week period. In the featured films, men abduct women, Asians are mimicked, Native Americans are dehumanized and slaughtered, African Americans are ridiculed and demonized (not to mention bought and sold).

But instead of presenting them without comment or judgment, TCM added intros and after-discussions in which its film expert hosts discuss the movies through “a modern lens.”

“Male domination as romantic fantasy” is discussed in connection with “Seven Brides,” a musical comedy in which seven backwoods frontiersmen kidnap seven women to be their wives.

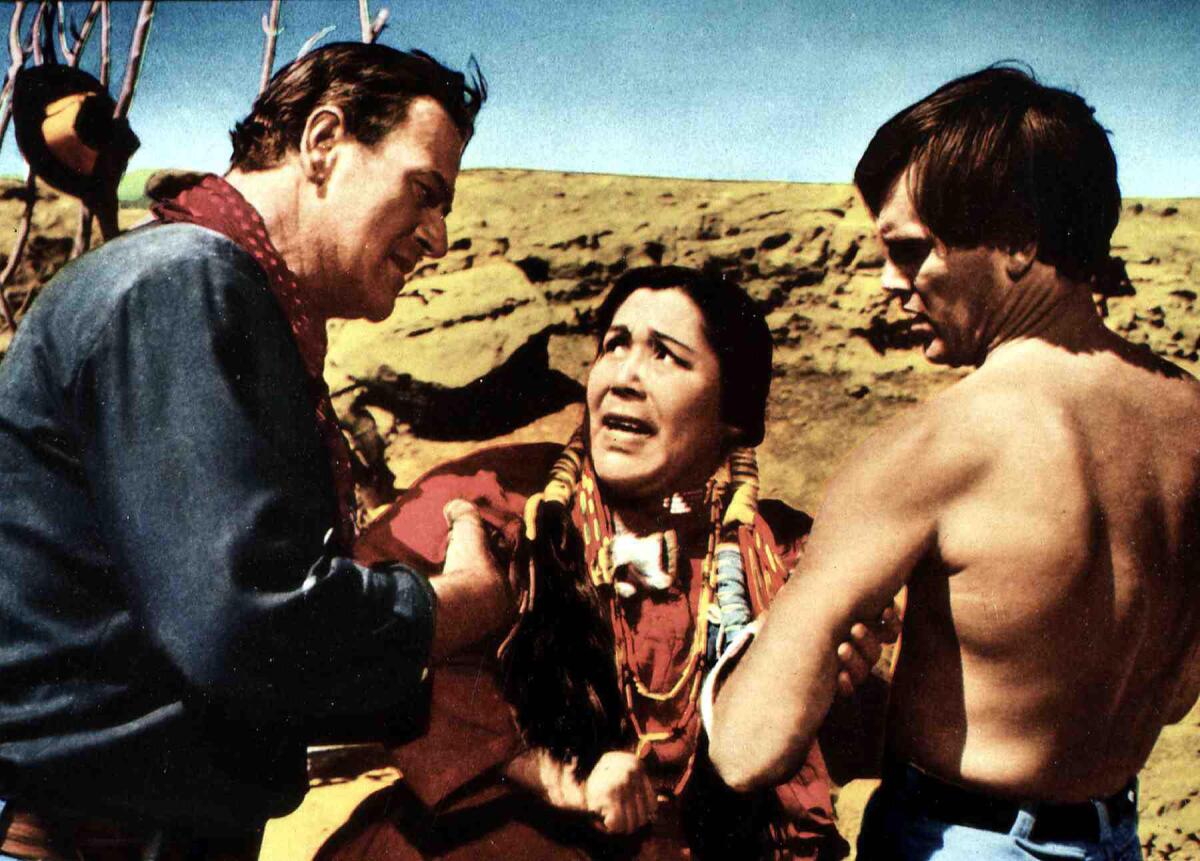

The swaggering, macho, anti-Native American vigilante played by John Wayne in “The Searchers” was debated by the experts: Was he a hero or antihero? “Gone With the Wind” was flatly (and rightly) characterized as “supporting a white supremacist point of view.” Mickey Rooney’s appalling comic portrayal of the Japanese photographer who lives upstairs from Audrey Hepburn‘s character in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” was discussed as a vile relic of World War II animosity.

Discussion. Analysis. Reconsideration of the prejudices, stereotypes and bigotry that suffuse these films. A review of the historical context in which they were made. These strike me as a healthy way to approach troubling old movies (as well as troubling books, statues and school names). Suppression, by contrast, is a form of denial, of erasing the reality of past attitudes.

Not that TCM did it perfectly. The “Reframed” discussions are heavy on white presenters, even though audiences might prefer to hear from more of the Native Americans, Asians, Latinos and others who were so often the targets of anger or ridicule. There is an annoyingly measured quality in the discussions — even of the most egregiously racist films. (Perhaps that was unavoidable from a group of avowed cinephiles speaking on a network whose core business, after all, is showing old movies.)

One of the big questions that went undiscussed in the segments I saw was how we should feel about these films. What if we fall for the romance of Rhett and Scarlett in “Gone With the Wind,” despite knowing all the reasons we shouldn’t? What if we root for cowboys over Indians in a western? Are these things unavoidable — or are they moral failings?

Still, I thought TCM made a serious good-faith effort toward a better, broader understanding of the nuance and complexity of our American past. According to Charlie Tabesh, TCM’s senior vice president for programming, “Reframed” has received some criticism from both the right and the left, but more of the objections have come from the right, with people complaining: “Don’t lecture me. I just want to watch the movie.”

“Reframed” comes in the wake, among other things, of a Los Angeles Times op-ed article written in June 2020 by John Ridley, the African American director, screenwriter and novelist, who called for HBO Max to remove “Gone With the Wind” from its rotation of films — and then after a period to return it to the air, presented with more context. HBO Max did exactly that.

After the summer’s racial justice protests — and a concerted push in recent years from within the industry — Hollywood is rethinking what gets made, who gets to make it and what from the past should still be shown. According to a recent article in the Hollywood Reporter, for instance, Disney holds a monthly meeting with a committee of outside advisors to discuss inclusivity, diversity, stereotypes and insensitivity in programming. Some studios and streaming services are using content warnings or disclaimers about negative depictions in old films.

There are lots of ways of addressing these issues. But sweeping history under the rug or pretending that those old wounds weren’t inflicted is the wrong way to go.

@Nick_Goldberg

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.