Column: The worst thing about impeachment? The lawyers

After three presidential impeachments, I’ve seen enough to conclude that one of the worst things about them is the lawyers. Even among some of my favorite legal commentators the problem is the same. They say something like: “Of course, impeachment trials aren’t criminal proceedings. Impeachment is a political process.” And then — often in the next breath — they’ll say stuff like “this wouldn’t work in court” or “the legal standard for incitement is a very high bar.”

This is a bipartisan phenomenon, manifesting itself among lawyers — and the politicians who defer to them — whether they favor or oppose impeachment. To a certain extent this is understandable. Impeachment involves a whole bunch of legalistic buzzwords — “high crimes and misdemeanors,” “due process,” “trial,” “conviction,” and, of course, “constitutional,” i.e., lawyer talk.

If, somehow, impeachment involved terms like “fulcrum,” “gage,” “cantilever,” or “modulus of elasticity,” engineers would probably feel entitled to dominate the debate.

The problem is that all of this legalistic talk spills into and infects an inherently political process, turning a mechanism of self-government into an episode of Perry Mason.

Calling something a political process doesn’t make it less serious than a judicial one. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau once said that war is too important a thing to entrust to the generals. He didn’t mean generals were irrelevant, just that the question of going to war was ultimately one of political statesmanship, not technical expertise. Thus, in the American framework, declaring war is properly left to Congress.

For similar reasons, Congress has the impeachment power. It is also too important to leave to the lawyers.

In a criminal court, if you’re found guilty of inciting lethal insurrection, you go to jail. In an impeachment trial if you’re found guilty of the same charge, you lose your job. Or, in Donald Trump’s case, the ability to hold it ever again. That’s it.

And yet, over and over, defenders of impeached presidents — both Republican and Democrat — make it sound like the highest principles of justice, the Constitution and the rule of law are at stake if the president isn’t afforded the full benefit of criminal legal standards.

It’s all nonsense.

For instance, in their defense brief, the president’s lawyers claim that Trump’s remarks egging on the crowd on Jan. 6 are protected under the 1st Amendment. They’re probably right. But so what?

The president of a corporation has every freedom to go on TV to declare that his company’s products are defective. But the board of his company could — and would — fire him according to whatever procedure they liked. If the head of the Smithsonian invited a mob to protest outside the Air and Space Museum and the mob ransacked the place because of lies he told them, the regents wouldn’t await a legal verdict before firing him.

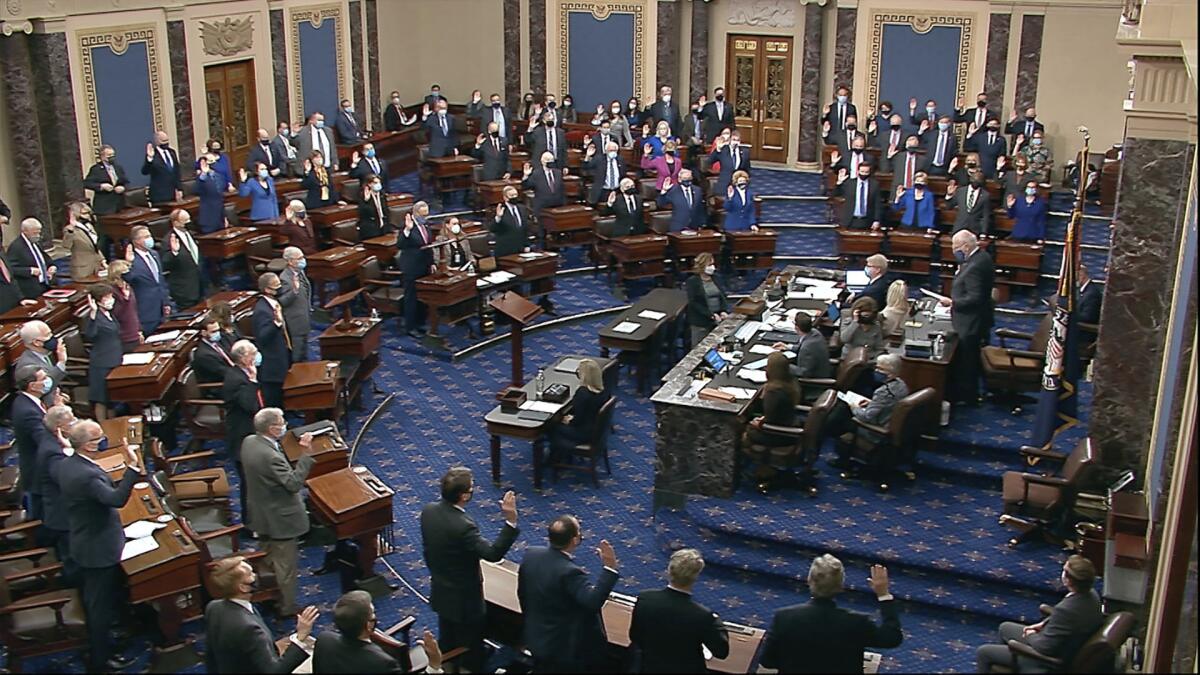

The Senate is like a board of trustees for the government. The Constitution gives the senators the authority to conduct impeachment trials as they see fit, subject to a handful of procedural rules. Even the judges in impeachment trials don’t function as judges would in a regular court; the Senate can overrule their decisions.

My analogy, while imperfect, is useful because impeachment is about self-government not criminal behavior. Yes, crimes can be impeachable, but as James Madison explained, impeachable acts don’t have to be criminal.

We all understand that private and most public institutions have every right to police the professional conduct of their officers. Why the standards for corporations, museums, universities, or Little League coaches should be so much higher than for presidents is a mystery to me. In almost every other realm of life, leaders are held to account not just to the law, but to notions of leadership, common sense and the basic decency and maturity we expect from responsible adults.

And yet, when it comes to the president, rigid legal casuistry suddenly defines what constitutes minimum standards of permissible conduct. You can say the presidency is different because it’s the one office the whole country votes on. Fine. But shouldn’t that be an even greater argument for applying standards of statesmanship, not criminal law? The founders thought so, which is why they made the Senate, not any court, the means by which we render judgment on such conduct.

But to listen to most Republicans today — or Bill Clinton’s defenders in the 1990s — the last thing that should enter into their thinking is statesmanship, never mind decency or maturity. They’d rather hide behind spurious legalisms rather than take their jobs or the facts seriously.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.