Editorial: Tap California’s pandemic ‘winners’ to help small businesses survive

Like thousands of other small businesses in California, EHS Pilates in San Francisco’s Mission District was forced to close its doors to clients during most of the pandemic.

The studio has been able to limp along so far by shifting to online sessions and outdoor classes and, for a few short weeks, in-person service at reduced capacity. As a business that relies on specialized equipment, this temporary arrangement isn’t cutting it. Operating at about 25% of normal is just not enough to sustain a business that supports the livelihoods of about 30 people.

EHS Pilates owner Tracey Sylvester said she has tapped her savings, taken out federal relief loans and negotiated a temporary break on the building’s $7,800 monthly rent to keep going these last difficult months. She’s now a little more than $100,000 in debt, including back rent. And though she is not sure how the business will survive, another loan is not an option.

Many of California’s 700,000 small businesses are in the same sinking boat. Even with federal relief, countless businesses have already called it quits. A poll commissioned by the Small Business Majority of 418 California small-business owners in November found that about 15% were facing permanent closure in three months. More than 20% said they would probably be forced to lay off workers, and 32% expected to cut employee hours. And this was before the stricter pandemic orders were issued in December.

Of course, not every business is hurting. The COVID-19 pandemic has produced winners and losers at every level of the economy. Many wealthy Americans saw their fortunes grow while millions of working people lost their jobs. Grocery stores, pot shops and other businesses considered “essential” during the pandemic have boomed, while thousands of others were forced to shrink or stop operations and watch their bottom lines bottom out.

The state’s nonprofits are feeling the pinch as well, particularly those providing arts or educational services that have been closed by the pandemic. Many of those that continue to operate have seen higher demand for services, but they’ve had to manage with the same or reduced operating funds. In just one example, the California Assn. of Museums estimates that its members are collectively losing $22 million a day.

These businesses and organizations are the backbone of the state’s economy and need help to survive until enough people are vaccinated for them to safely resume operation. And it is only right that the help come from those who have done well during the pandemic.

Last spring, state officials were bracing for a pandemic-caused deficit as high as $54 billion. But that forecast was wrong. Instead, the state government is expecting a $15-billion surplus due to tax revenue from high-income Californians who saw their fortunes rise during the pandemic. This is a one-time bonus that should be put to use immediately to help the state recover from a year of COVID-19, and the governor has appropriately designated billions toward pandemic initiatives, including a $4.5-billion economic stimulus package.

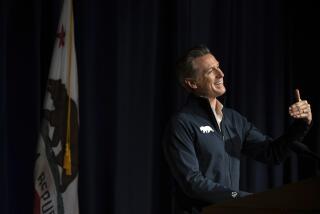

But so far only $500 million has been set aside to help small and micro California businesses and nonprofits that are in dire financial straits. It’s not nearly enough. How do we know this? Because when the Newsom administration launched a relief program in November for small businesses and nonprofits hurt by the pandemic, it received more than 300,000 requests for grants ranging from $5,000 to $25,000 — and that’s only those that were able to navigate the clunky application process.

Newsom has proposed expanding this program by $575 million this year. But a large bipartisan group of legislators is pushing for $2.6 billion, with a higher maximum grant to match the scale of the need. We agree, though even that sum will probably not be enough to help every business and nonprofit that needs it.

But first the state must commit to more transparency in the administration of the money. The nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office examined the new grant relief program and found that there’s no way to gauge whether the grants are being distributed fairly and to those who need it most, such as those not eligible for federal relief. That’s not acceptable. This is public money and we need to know exactly where it’s going, as well as the criteria used to evaluate grant applications.

This isn’t charity; it is justice. Public health measures dictated that some businesses would stay open and others would be forced to close. That was necessary but not always fair. And without immediate state help, many of the businesses and organizations serving and employing California may close permanently, taking their jobs and vital goods and services with them.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.