Editorial: Martin Luther King’s Promised Land may be closer than we think

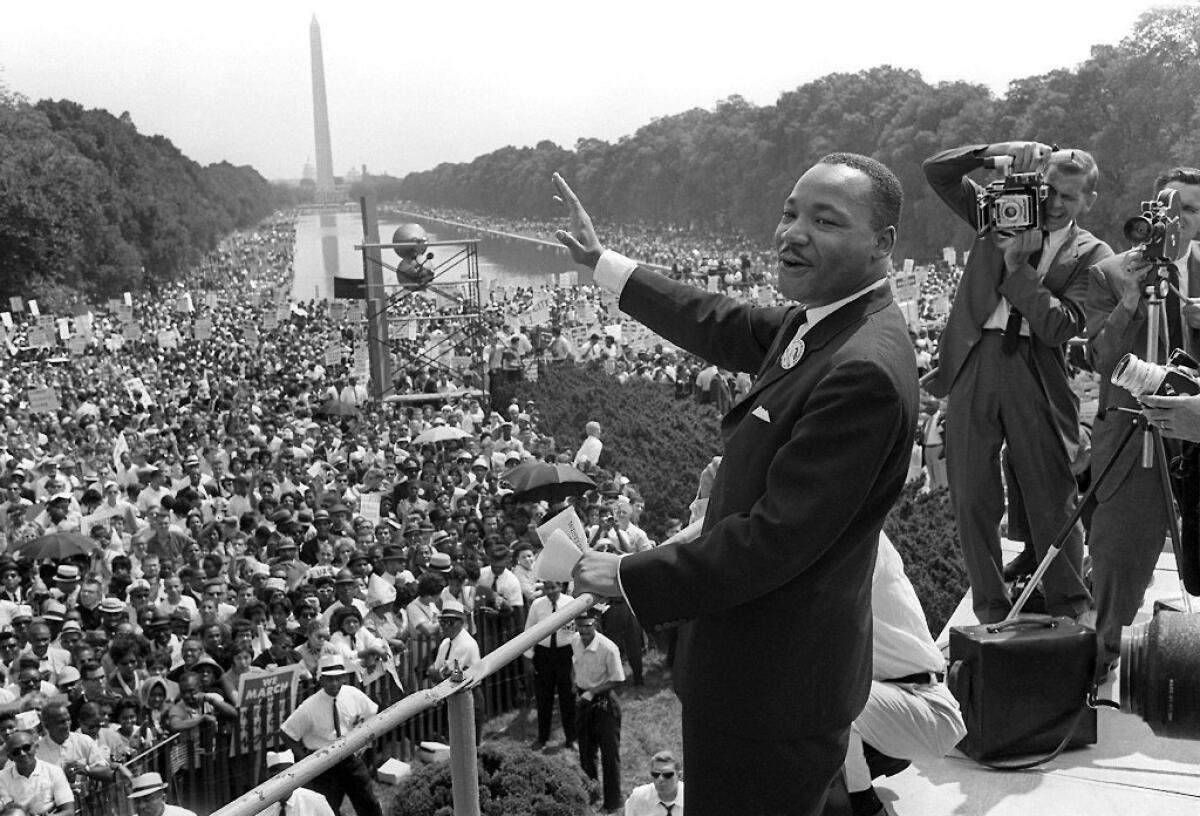

What would the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. make of this tumultuous past year? On the evening before he was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn., he told hundreds gathered in a church, in words that would become among his most famous, that he had been to the mountaintop and seen a better world to come. And though he might not get there with them, he pledged that “we as a people will get to the Promised Land.”

Some 53 years later, that destination remains elusive. There was no promised land for George Floyd as he lay begging for his life under the knee of the police officer who killed him. Nor was it there for Breonna Taylor, shot to death by police officers who burst into her home.

Yet, if police brutality against Black people like Floyd and Taylor still exists, it was countered by the new reality of tens of thousands pouring into the streets in this country and elsewhere saying they would no longer tolerate it. Black, white, brown and Asian people left their locked-down pandemic lives at home to march through downtown and suburban streets, in Black and Latino neighborhoods and in wealthy white enclaves to support the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s as if those protesters, risking COVID, had unknowingly channeled the words of King that night in Memphis when he urged his audience to join a march for striking sanitation workers, even if it meant leaving their job or school and practicing “dangerous unselfishness.”

Those marches led to nothing less than a social upheaval, a reckoning, a calling out of racism embedded not just in police departments but throughout society, in businesses, schools, the film and TV industry and the news media. (The Los Angeles Times is having its own reckoning, which has led the company to pledge to hire more journalists of color, reexamine how we report on people of color, and make a public apology for racist coverage in the past.)

“Martin King would not be surprised that the violence of the police has not changed yet,” said James Lawson, who worked side by side with King and taught nonviolence workshops in the South. Added Lawson in an interview: “This is really the first time that the U.S. has been challenged with the question — what kind of law enforcement do you need in a democratic society? Now BLM has asked, why do traffic cops have to have guns?”

At 92 — the age King would be had he lived — Lawson, a pastor emeritus at Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles, is one of the diminishing number of King’s compatriots still alive to see how the movement King led has evolved and how it hasn’t. Just last year brought the death of another King confidant, John Lewis, the revered civil rights activist and Democratic congressman from Georgia.

Lawson, too, drew a parallel between King’s work at last summer’s protests. “Black Lives Matter,” he said, “is the 21st century emulation of the Martin Luther King-Rosa Parks nonviolent civil rights movement of the 20th century.”

In the last year, statues of Confederate generals have been pulled off public display at schools, in town squares and in government building courtyards. However, the steps forward often came with steps in reverse. Only 12 days ago, in one of the most unnerving scenes from the insurrection at the Capitol, a white rioter strode through its hallways carrying a Confederate battle flag.

The idea of people clinging to the Confederacy in 2021 is alarming, but it must be offset by the extraordinary rise of Black voting power in battleground states in the South and elsewhere. Black voters turned out in record numbers — largely due to the herculean organizing efforts of Black women activists — to help elect Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, the first Black and South Asian woman to become vice president. Then, in a pair of stunning upsets fueled in part by Black voters, Georgians elected the Rev. Raphael Warnock — the first Black Democrat voted into the U.S. Senate from the South — along with fellow Democrat Jon Ossoff, the first Jewish senator from the state.

Warnock is also the pastor of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King was famously a co-pastor. It would have been unfathomable half a century ago that the Georgia pulpit of a civil rights leader would successfully launch a Black preacher into the Senate.

If he were alive today, King might find it hard to discern much good in the past year, with so much death from COVID-19 (disproportionately for Black and Latino Americans), so much unrest and so much violence. But he would find solace in the fact that enormous, multiethnic throngs took to the streets after Floyd’s death, forcing communities across the country to confront the stain they’ve failed to erase. That work — his work — goes on.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.