Op-Ed: To persuade Georgians to vote, I learned to slow down and engage. It works

“This is ridiculous,” I say to my husband.

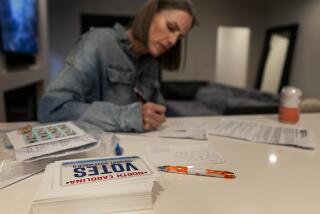

It’s August, and I’ve just muted myself during a Zoom meeting. Along with a hundred or so volunteers, I’m about to call Southern voters with a group called Showing Up for Racial Justice, or SURJ. Two organizers are role-playing our script for phone banking. But the hypothetical call is going on and on. After 15 minutes, the New Yorker in me is growing impatient.

Getting red-state voters to support a Democrat — the mission of SURJ’s Swing Georgia Left initiative — is already a herculean task. At this rate, we’re not going to reach many people.

I was wrong.

By election night, more than 3,800 volunteers had spoken to 36,000 voters and secured 21,200 commitments to back Joe Biden for president. He would beat Donald Trump in the state by 12,000 votes. SURJ, working with partners such as the New Georgia Project, achieved its remarkable goal.

And we’re still at it. Democratic control of the Senate rests on twin runoffs in Georgia, and volunteers for SURJ are back on the phones until Tuesday, the final day of voting.

There is a method to their madness, and it begins with those unhurried conversations.

::

Southern women founded SURJ during the Obama years. Republicans were driving a wedge between working-class whites and progressive, multiracial activists — even though the latter’s agenda (a minimum wage, job protection, healthcare) had much to offer low-income whites.

Liberal campaigns had written off the South for decades, creating a dangerous void. “If neutral or conflicted white voters only hear from those who are using racism strategically to maintain power, the message sticks,” Erin Heaney, SURJ’s national director, wrote in April.

Four years of Trump’s scapegoating and racist rhetoric led to Swing Georgia Left. In everything it does, SURJ answers the call of visionary Black leaders , who have historically called for white people to organize their own.

Still, I have my doubts: Will these voters answer the phone? Will they engage in long conversations? And will they really share the personal information we need to register them to vote, or track an absentee ballot?

The answer is an emphatic yes.

The result is some of the shrewdest, most effective activism I’ve seen. And it’s all grounded in empathy.

If someone says, “I’m not planning to vote,” we don’t hang up and move on. Instead, we say, “ I hear you. There’s so much going on these days. A lot of people are tempted to skip voting.” We take our time. We hear them out. And then we might ask: “How are you doing during the coronavirus?”

That query often leads to a heart-wrenching list of hardships.

“My partner is sick.” “I lost my job.” “I haven’t seen my parents in months.” Listening leads to conversations about the current administration and the need for change — specifically, the need to vote.

Religion has taken on new meaning in this heated political season amid the Georgia Senate runoff races, where a Black pastor from Martin Luther King Jr.’s church is on the ballot.

However long it takes, we find out how people are feeling, really feeling, about the election this year. During the general election, for the nonvoter who’s losing sleep over healthcare, I can talk about Biden’s plan to protect people with preexisting conditions.

As the conversations deepen, my skepticism melts away. In the course of one call, I ask a woman if she’s planning to vote. She tells me, “I’m gonna vote this year if I have to crawl over broken glass.”

Given Georgia’s history of voter suppression, she nearly does.

She describes a long ordeal. After moving and applying for a new driver’s license, she’s told her address will be changed automatically on voter rolls. Nine weeks later, it’s finally done.

Another woman, a lifelong Democrat, says that her husband, a hard-core Republican, is voting for Biden. “This is the first time in 54 years that we’re voting for the same candidate,” she adds.

Swinging Georgia blue is beginning to seem possible.

Meanwhile, our script keeps changing to reflect new realities. By October we can say, “Joe Biden and Donald Trump are tied in Georgia. Your vote can make all the difference.”

As the election draws nearer, our questions are more precise. “Do you know where to go to vote early?” “Will you drive to the polling station?” “Will you go before work or after?” Short of asking what they plan to wear, we help people visualize a voting plan. The more concrete that plan, the more likely they’ll follow through.

::

A few weeks before the election, I have a conversation that changes everything for me.

A voter tells me that she supports Biden, but — surrounded by Trump voters — she needs to stay quiet about it. “I was in a store wearing a mask,” she says, “and a woman punched me in the arm.” Living in Manhattan, in a bubble of Democrats, I’m horrified. We talk for another 10 minutes about our different experiences.

I don’t think of myself as a cynical New Yorker, but yes, I’m always in a hurry. And in my rush for results, I was wary of this long-winded approach. In slowing down, I discovered the power of one-on-one connection.

Listening, which takes time, is active. And as a strategy, it is powerful and pragmatic.

SURJ is a well-oiled machine, but never slick. And yet — why do I feel the need to write that last sentence, as if something so highly efficient can’t also be full of compassion and humanity?

We have certain assumptions about what it means to get things done, about what constitutes action. SURJ challenges all of them.

Deep listening is a powerful force against cynicism. For four years, we’ve seen shameless and relentless bullying at the national level, a politics of intimidation and fear. Republicans went low, and then they went lower. But for us to lose faith in thoughtful engagement would be their ultimate victory.

SURJ reminds us that, in the next four years, great things can come of goodness and decency, combined with a bit of shrewdness and skill.

And that’s exactly what SURJ is banking on every time we call a voter.

Cathy Tempelsman is adapting her play based on the life of George Eliot into a screenplay, “Dangerous Woman.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.