Rudy Giuliani has tried to subvert the will of the voters before. He did it after 9/11

The problem with Rudy Giuliani isn’t that his mascara runs or that he held a post-election event next to an adult book shop. Nor is it his behavior toward the young woman in the Borat movie or his pinkie ring or the fact that he told his second wife he was divorcing her by announcing it at a news conference.

The problem with the former New York City mayor is that he doesn’t respect elections.

Not only has Giuliani been President Trump’s chief accomplice in his outrageous and deceptive efforts to subvert the will of the American people, a role he is continuing to play even as the transition gets underway, but he also fought hard in the aftermath of 9/11 to keep himself in office after his term as mayor ran out.

Let me remind you what happened then.

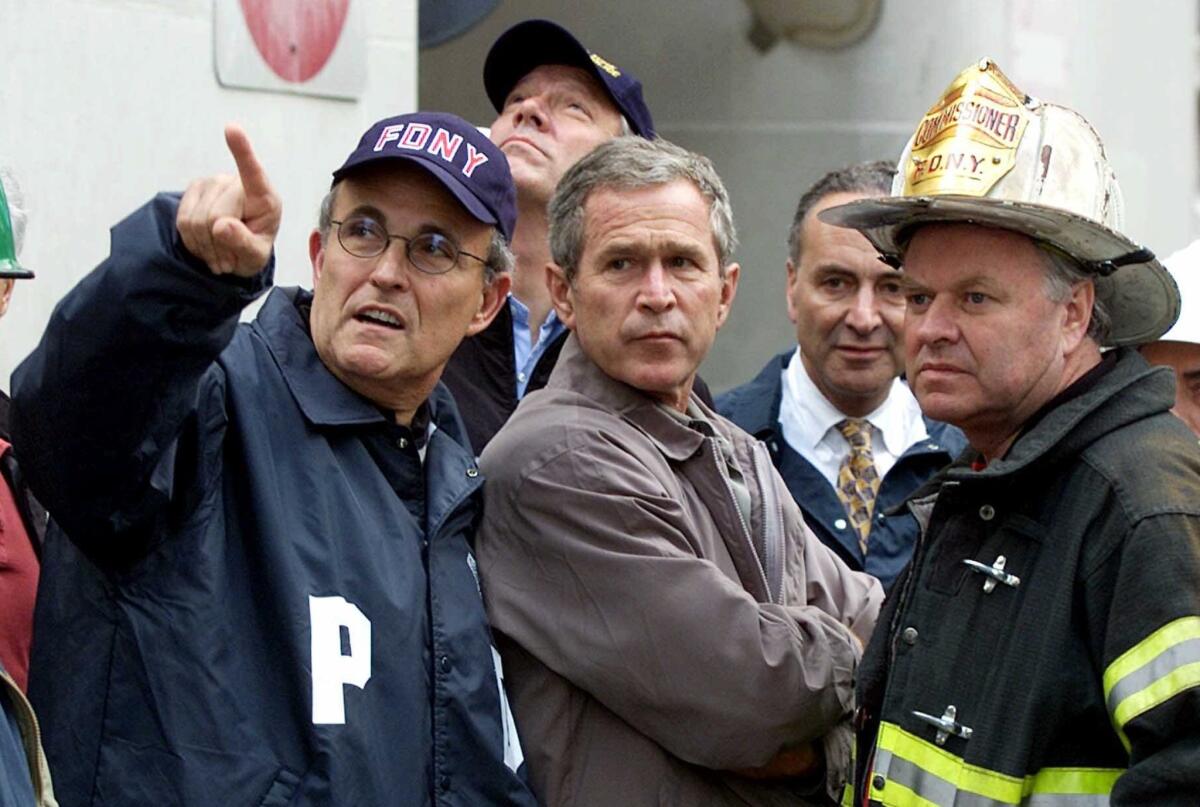

Sept. 11, 2001, in New York City was a crisp, shockingly clear fall day. When the two World Trade Center towers were attacked, and then collapsed in a cloud of dust, steel and concrete, then-Mayor Giuliani rose to the occasion, emerging from an office two blocks away covered in ash but ready to defend the city. He was calm and commanding in the days that followed, supporting first responders and comforting survivors and speaking effectively for an anxious city. He revived his battered political image, reinventing himself as “America’s mayor.”

Sept. 11 was also primary day in New York City. A mayoral election was underway. Giuliani was termed out — it was the end of his second term and his time in City Hall was up at the end of the year. More than half a dozen candidates — including Mark Green and Michael Bloomberg, who eventually became the nominees in the general election — were fighting for their parties’ support. Because of the World Trade Center attacks, that day’s primary was put off for two weeks.

Delaying the primary was entirely reasonable. People weren’t going to turn out to vote on a day when the city had been violently terrorized.

But Giuliani saw an opportunity for something else. In the days that followed — as he watched his poll numbers rise — Giuliani and his aides and supporters began hinting that the mayor shouldn’t be required to leave office when his term was up. What the city really needed was an extraordinary three-month extension of his term to help deal with the fallout of the attack and ease the transition for the next mayor. This was a catastrophe after all. Steady leadership was needed. The November election should be canceled.

Or maybe that wasn’t enough. In fact, according to Giuliani and his aides, the 1993 law barring him from serving a third consecutive term should be overturned entirely if his bid for an extension was rejected and he should be allowed to run again. Giuliani even considered trying to get himself on the ballot despite the term limits law. He lobbied the governor and the Legislature to keep him in office.

Trump-like, Giuliani insisted that supporters were “begging me to stay in the run for another term.”

He got some support in the heat of the crisis, but a lot of pushback too. The New York Civil Rights Coalition accused Giuliani of bullying the mayoral candidates and being “disruptive to electoral democracy.” The Democrats in the state Assembly (whose support was necessary for any extension) refused to back his proposal. Frederick A.O. Schwarz, who had served as the city’s top lawyer, said Giuliani had “created the very dangerous idea that we couldn’t survive without him.”

Republican Gov. George Pataki wrote later that Giuliani’s team “pushed the issue” with the governor’s staff for weeks. Pataki finally told Giuliani he would neither support an extension nor cancel the upcoming election.

“Regardless of Rudy’s motivation, regardless of his raw emotions in the situation, he abandoned some of the most basic conservative principles — to follow the law and relinquish power when your term is over, even in times of crisis,” Pataki wrote later.

Sound familiar?

Another opponent of Giuliani’s attempted power grab was his friend Arizona Republican Sen. John McCain, who advised the mayor to back down. According to ABC News at the time, McCain cautioned Giuliani to “listen to people you trust, not people who have a stake in your decision.”

When it became clear that state leaders would not authorize his continuing on as an unelected mayor, Giuliani gave in. But he appears to have learned nothing from the experience.

Even as he approved starting the transition, Trump refused to concede and may well never do so. His tactics — and Giuliani’s — have undermined the integrity of a legitimate election in the eyes of Americans and deepened the fissures in an already deeply divided country.

It is precisely in times of crisis — whether a terrorist attack or a pandemic — that democracy must show its resilience. Rules, laws and norms, including elections, obviously shouldn’t be tossed aside at the first signs of strain.

That’s a lesson Giuliani should have learned two decades ago when the towers came down.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.