Op-Ed: One fix could change U.S. politics, government and elections for the better: Make voting mandatory

The United States should require every eligible American to vote — or at least participate — in general elections.

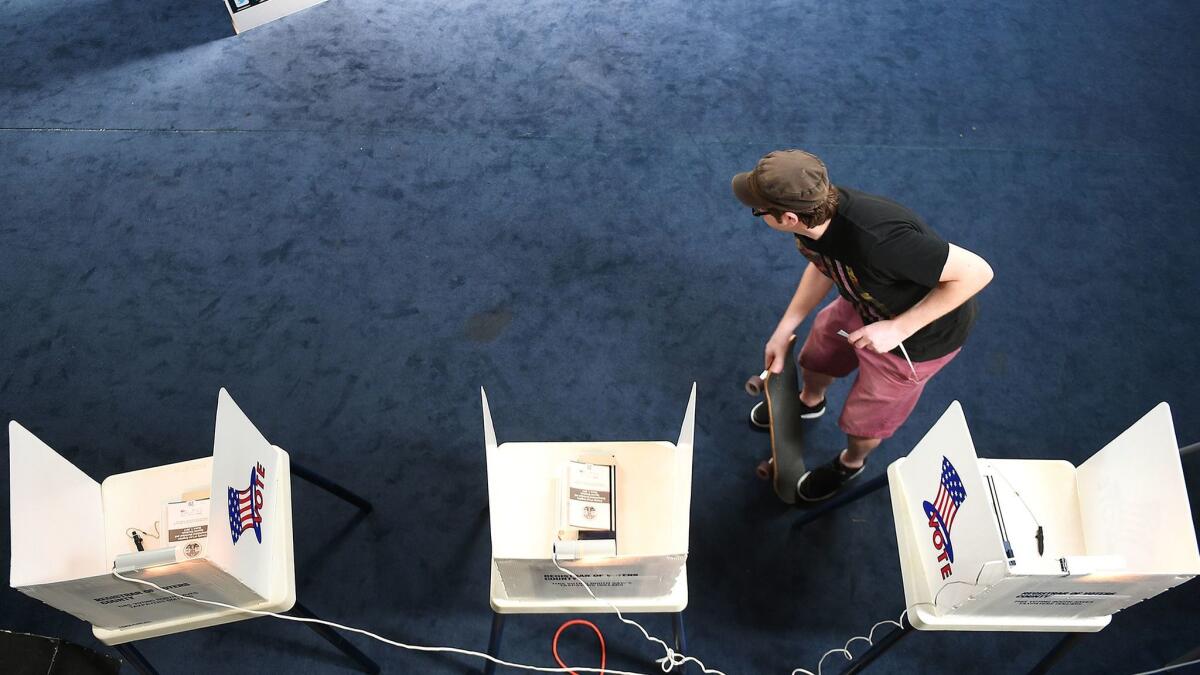

As states and municipalities strive to make the 2020 elections full and fair amid political controversy and the limitations imposed by the pandemic, it should be remembered that even in normal times, our elections have two crucial shortcomings: low voter participation and an electorate that does not reflect the nation’s increasingly diverse population.

The solution to both problems is straightforward: Make voting a universal civic duty. Mandatory voting is already in place in 26 countries, including Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Ecuador, Greece, Singapore, Switzerland and Uruguay.

In Australia, participation in elections has been mandatory since 1924. The government, political parties and civic groups all work to educate citizens about their responsibilities and to make voting fully accessible to all. Election day, which falls on a weekend, is treated like a community celebration. Although participation is mandatory, choosing a candidate is not: Voters can cast a blank ballot or provide a “valid and sufficient reason” to abstain. After each national and state election, those who did not participate are sent a letter asking why. If no reason is supplied after two attempts, the nonparticipants are fined the equivalent of about $15.

The system is widely popular in Australia and functions well in other countries too. Yet there has been virtually no discussion of this potentially game-changing policy in the United States. We are now seeking to change that.

For two years, 27 scholars and advocates, including the two of us, have studied mandatory voting. Our conclusion is that adopting universal civic-duty voting in the U.S. would have major benefits for American democracy.

It would dramatically increase participation in elections. In Australia, Belgium and Uruguay, participation rates have remained near 90% for the last two decades. In the 2018 midterms, the U.S. achieved a much-touted record turnout, but still only an anemic 53.4% of eligible voters cast their ballots; in 2014, the figure was 42%.

Mandatory participation would also diminish the demographic skew at the ballot box. Voting rates now vary dramatically by income, education, age and race. Although African Americans vote in higher proportions than whites when income is factored in, communities of color, especially African Americans, have faced a variety of voter suppression policies and tactics.

One reason jury service is mandatory is to assure that jurors will reflect the population as a whole, and that, as a result, they will render fairer judgments. The same logic applies to voting. Near universal participation among America’s racially and ethnically diverse voting-eligible population will yield more equitable and responsive representation.

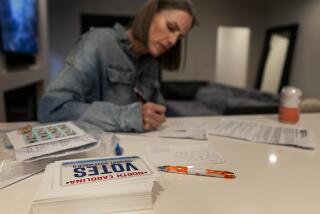

The adoption of universal civic-duty voting could also help shift our election laws away from policies that, intentionally or not, keep some groups from the polls. It would encourage same-day registration, ending felony disenfranchisement, pre-registering 16- and 17-year-olds, paid leave to vote, and expanded early and mail-in voting. Schools would have a strong incentive for robust civic education to prepare 18-year-olds to vote. Civic organizations could invest more in public education about voting, and spend less on driving voter turnout.

It’s even possible that political campaigns would change for the better. If everyone is voting, then everyone is listening, and candidates and parties will need to make efforts to attract broad support, rather than focusing solely on rallying their base supporters and discouraging turnout on the part of their opponents.

There will be resistance to the idea of civic-duty voting. Libertarians will object to another government mandate, and challenge the idea’s constitutionality. Among advocates for low- income and historically marginalized communities, imposing even a small fine may raise alarms. And some may worry that a voting requirement would encourage ineligible voters to participate.

We took all these objections very seriously.

We believe the proposal is constitutional, since a blank ballot, a vote for “none of the above” or acceptance of a conscientious objection to voting will assure all voters of their ability to “speak” as they wish. Our current system has effective safeguards in place that, coupled with public education, can ensure against inadvertent violations by ineligible voters.

As for enforcement, states and municipalities can offer community service as an alternative to paying a fine, or they could employ incentives as opposed to penalties to minimize potential adverse effects of whatever enforcement mechanism, however slight, is in place.

This election year, the United States finds itself questioning old assumptions and seeking new ideas to further its goals of justice and equality. For those of us who have fought for decades against voting restrictions and for the right of communities of color to have their voices fully heard, universal voting is a powerful innovation. In this moment of reckoning and change, it could be a giant step toward a truly inclusive democracy.

Miles Rapoport, formerly Connecticut’s secretary of the state, is a fellow at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the Harvard Kennedy School. Janai S. Nelson is associate director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.