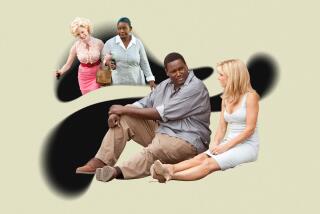

Opinion: Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben aren’t just racist symbols, they flatten culture for white consumption

It took decades, but Aunt Jemima is retiring, with Uncle Ben soon to follow. Mrs. Butterworth is also being rethought.

These characters have their origins in longtime racist stereotypes.

Black writers have long traced Aunt Jemima to minstrelsy and the “mammy” symbol, a caricature of Black women that casts them as happy in their domestic service to white families and loyal to the institution of slavery. As Riché Richardson pointed out in 2015, the white founders of the pancake mix brand drew “inspiration” from the minstrel song “Old Aunt Jemima,” a staple that was performed by men in blackface. “Uncle,” in a similar vein, was used by white Southerners as a pejorative for older Black men whom they refused to address with the more respectful “Mr.”

Let’s not kid ourselves — the renaming of commercial brands doesn’t solve racism, especially because corporations from Amazon to PepsiCo (which owns Quaker Oats, maker of Aunt Jemima) take a stance on social issues only when it helps their bottom line. But it’s also true that cultural symbols matter. Who we read about in textbooks, see honored in statues, and portrayed on television shapes how children and young people in particular see themselves and the possibilities that are open to them.

Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, Land O’ Lakes, Trader Ming, Miss Chiquita and the countless caricatures of Black, indigenous, and other people of color baked into American popular culture are part of a long history of white people flattening “ethnic” culture and peoples into digestible, safe symbols that they can, literally, digest.

A large part of this comes from the need to appeal to the white consumer — stripping yoga from its religious roots, for instance, and placing a white person at the front of the room to make it less “mystic” or “exotic,” also makes it easier to sell to white consumers. Throw in a few baby goats, and you’ve got a “safe” and utterly disrespectful way for white people to “experience Indian culture.”

Seeing a happy Native American woman on a Land O’ Lakes box (which has since been changed) or watching Disney’s Pocahontas helps one forget that indigenous people are modern communities, not long-vanished peoples, and that the Navajo Nation, the country’s largest reservation, had a higher coronavirus death rate than any state in America as of mid-May. It’s the same reason why white people open psuedo-Chinese restaurants like Lucky Lee’s to make “healthy” and “clean” versions of dishes that white consumers see as more “accessible” than “dirty” food prepared by actual Chinese chefs.

The persistence of racist caricatures such as Aunt Jemima are a reminder to people of color that they are rarely allowed to occupy positions of cultural prominence unless they are tokenized. As our society strives toward racial inclusion, diversity in representation should not mean “sanitized” versions of people of color or their histories. When Alex Lau, a former Bon Appétit photographer, questioned why the company didn’t want to shoot African food and recipes, he was told that they were “tricky,” and that “readers probably wouldn’t want to make the food.” Telling the stories of people of color in their full richness and complexity, rather than reducing them to a trope for a white audience, is crucial.

Getting rid of racist cultural symbols — from replacing Columbus Day with Indigenous People’s Day to finally rebranding Aunt Jemima — is a first step toward correcting a sanitized, Eurocentric view of history and culture. Whether we like it or not, these symbols are used to dictate who gets to “belong” to American culture, as well as the ways in which they are allowed to belong. For people of color, and Black and indigenous people in particular, acceptance in American society has, for too long, meant flattening oneself into white standards of acceptability and respectability, becoming the pleasant and placid Aunt Jemima or Miss Chiquita or Trader Ming. It’s long past time to retire these harmful stereotypes.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.