Opinion: SoCal’s new housing plan is going to make traffic and air pollution worse for everyone

In August, Gov. Gavin Newsom directed the Southern California Assn. of Governments to develop a plan to build more than 1.3 million new units of housing. It’s no secret that Southern California is suffering from soaring housing costs, homelessness, traffic congestion and greenhouse gas emissions caused by a historic failure to plan for housing. NIMBY stonewalling has prevented serious action on any of these fronts.

Newsom’s mandate was intended to force Southern California’s hand to take meaningful action to confront its various crises.

For the record:

8:50 a.m. Oct. 25, 2019An earlier version of this story stated that Santa Monica’s proposed housing target was less than 2,000 units. It is 5,000.

SCAG recently published this plan. The results were disappointing, to say the least.

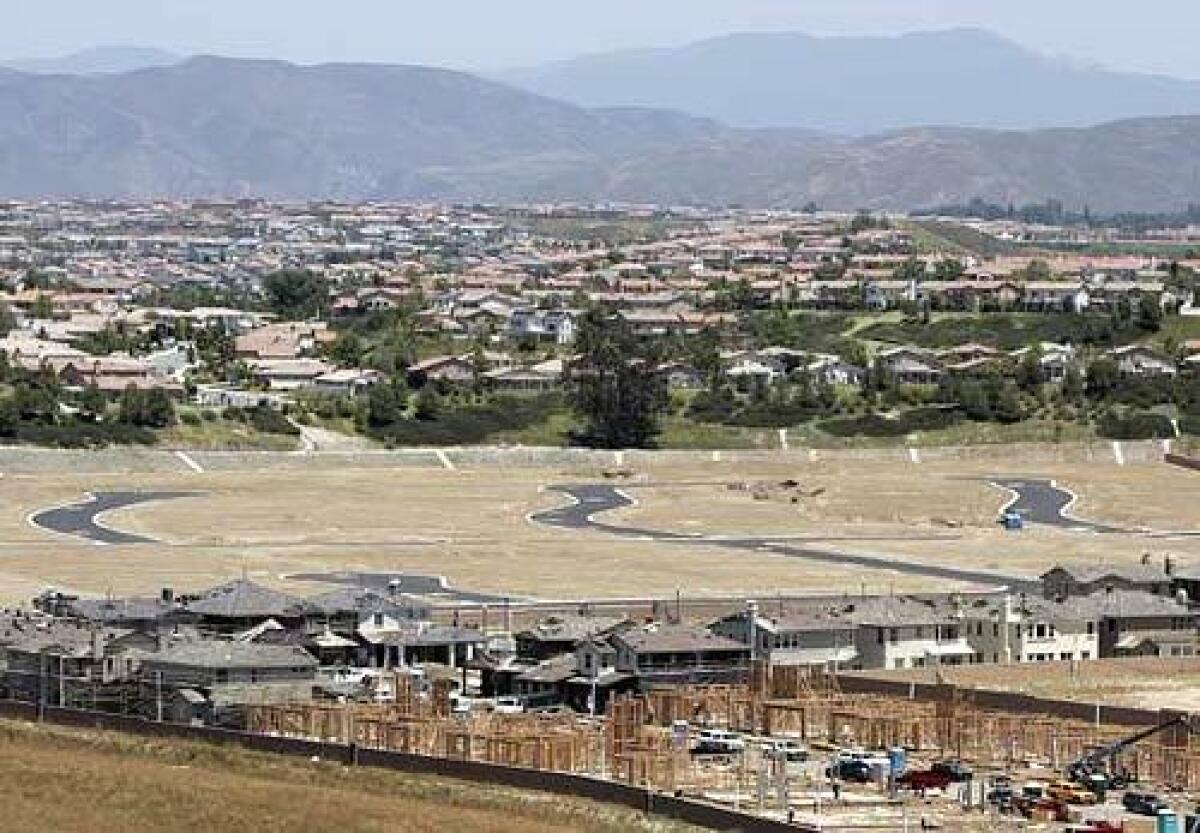

Instead of making the radical changes Newsom was looking for to fight the housing crisis, SCAG’s approach is more of the same: It leaves wealthy, exclusionary cities with massive jobs pools alone in lieu of disproportionately dumping housing into the sprawling exurbs.

According to SCAG, Beverly Hills, which has nearly twice as many jobs (57,000) as people (34,400), needs only 1,373 new units of housing. Meanwhile, the desert city of Coachella, with a population of 42,400 and 8,500 jobs, will be expected to build a whopping 15,154 units.

Santa Monica, with its growing Silicon Beach tech hub, employs nearly 90,000. And yet SCAG’s housing requirement for the city is 5,000. Then there’s Expo Line-adjacent Culver City, which already hosts 44,000 workers and is undergoing an influx of thousands more jobs from companies like HBO, Amazon and Apple. SCAG seems to think 1,660 homes is sufficient there, while distant Inland Empire cities like Riverside and Fontana get 20,139 and 22,126, respectively.

SCAG has the gall to lump this plan under the banner of its so-called Sustainable Communities Strategy.

“But Coachella Valley’s a nice place,” Margaret Finlay, a Duarte City Council member and former SCAG president, said before voting in support of the plan. “You move where you can afford to live, and you get a job there.”

Ideas and commentary on building a livable, sustainable Los Angeles.

Unfortunately, that’s not how the real world works. We know exactly what the results of this housing/jobs imbalance will be: more mega-car commutes and the continued rise of greenhouse gas emissions.

Already, more than 150,000 people in L.A. County spend at least three hours commuting. And passenger vehicles are the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in California. On top of that, if SCAG’s plan goes forward, remote cities like Coachella will have to significantly grow their footprints, irreversibly destroying the natural environment to make way for sprawl.

And it gets worse. When cities with transit and jobs don’t build enough housing, it drives up costs in those areas, ensuring only the wealthy can afford to live there. Newsom’s 1.3-million-unit housing mandate was intended to relieve residents from the crushing pressure of high rents. But pushing housing into the exurbs will do little to nothing to ease the crisis.

For years, SCAG plans like this one were only marginally consequential. Under state law, every eight years California is required to create a housing needs assessment that sets targets for each region of the state. In response, regional government groups like SCAG work with cities to plan where that housing should be built and what kind of rezoning would be needed to hit the targets. But the mandate has never had teeth, until now.

Historically, there was no enforcement mechanism to make sure cities built their allotted housing. This time around new state initiatives have changed that. To avoid financial penalties, cities will have to rezone in accordance with their regional housing plans. And if they fail to meet housing production targets, new state laws streamline the housing development process, allowing builders who include affordable housing in their projects (and follow other state guidelines) to sidestep any additional NIMBY red tape.

Moreover, Newsom has made it clear he is taking compliance seriously. In January, his administration filed a lawsuit against the city of Huntington Beach for failing to allow enough new housing to be built as required under state law. He has stated that transportation funding may be withheld for cities that fail to sufficiently plan for his housing goals.

And yet there is still a major problem. While SCAG is required by law to distribute housing based on objective factors, including access to transit, jobs/housing balance, and housing costs, it has chosen to minimize these factors in its distribution plan. Instead, it relies mostly on “local input,” a non-objective method based on projections of household growth under current zoning. In other words, a method that incorporates NIMBY preferences to exclude housing.

So what should Southern California’s housing distribution look like?

Abundant Housing L.A. research director Anthony Dedousis, along with UCLA urban planning professor Paavo Monkkonen, recently developed a data-driven methodology to determine just that, using current population as a base and adjusted exclusively for statutory objectives like jobs/housing balance and transit accessibility. Under this approach, Coachella would receive 1,565 units of housing while Culver City would get 5,114. Riverside would get 16,103 units, while Beverly Hills would get 7,576. Santa Monica, with its massive job base and access to rail, would get 14,155.

On Nov. 7, the SCAG Regional Council, which includes L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti and every member of the Los Angeles City Council, has a chance to push us in this direction. They should reject SCAG’s plan, and instead shape Southern California’s future housing based on jobs, transit, traffic and affordability. They should demand that expensive cities with jobs accept more housing for low-income workers.

Transforming Southern California into a place where people can find affordable housing near where they work or where they want to live — without destroying the planet — requires smart, data-driven planning. Pushing the region’s housing out of sight and out of mind is the exact opposite of what we need.

Leonora Camner is managing director of Abundant Housing LA (@AbundantHousing)

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.