Are humans hard-wired for racial prejudice?

Reaction to the acquittal of George Zimmerman was just the latest reminder: Race continues to divide us as a species.

But why? Are human brains hard-wired to notice and react to racial differences? At first glance, that’s precisely what research seems to demonstrate.

Some of the most compelling evidence for a hard-wired racial divide concerns a brain region called the amygdala, which plays a central role in processing fear and aggression. If you were put in a brain scanner that identifies levels of activity in different regions and shown a picture of something scary, your amygdala would leap into action, telling your heart to race and your skin to get clammy. It would also help you decide what to do next: Run like hell? Pull the trigger? Wet your pants?

Most regions of the brain are “told” what you are seeing only after that information has first been processed by specialized areas of the cortex — a glacially slow process (by neurobiological standards, that is; it takes about half a second). But the amygdala can get information far more quickly, through pathways that bypass those lumbering cortical regions. The amygdala can register information that appears for less than one-20th of a second, a time so short that you aren’t even aware of what you saw. And unfortunately, that information isn’t necessarily accurate.

So how does race enter into this picture? Numerous studies have found that if you put someone in a brain scanner and show him brief flashes (one-20th of a second) of emotionally neutral faces, the amygdala activates if the face is someone of a different race.

Now consider a brain region called the fusiform cortex, which specializes in detecting faces. Work by John Gabrieli at MIT shows that the fusiform isn’t as active when viewing the face of someone of another race. It’s not about novelty: Show a face with bright purple skin and there isn’t that blunting of the fusiform response. Other studies have shown that brain regions involved in empathy are more active when seeing a needle poking a finger with your own skin color than one of another race.

All this plays out behaviorally too. In work by Joshua Correll at the University of Colorado, volunteers played a video game in which they rapidly saw pictures of people holding either a gun or a cellphone, with the instruction to shoot only those with guns. When white participants (including police officers) were shown an African American, they tended to shoot faster and were more likely to mistake a cellphone for a gun.

All this is not only depressing, it’s puzzling, if you think about it.

For the majority of human history, people lived in hunter-gatherer bands where they never met anyone of another race. The nearest such person was likely to be hundreds or thousands of miles away. It’s only extremely recently, in evolutionary terms, that humans have become mobile enough to encounter other races. Why, then, should our brains have evolved to have such automatic, inevitable, aversive processing of people of other races when such encounters have played virtually no role in how humans evolved? The answer is, they haven’t. The aversive processing is neither automatic nor inevitable.

For starters, all the studies discussed found individual variation. Not everyone has an overactive amygdala, an underactive fusiform or an itchier trigger finger when seeing someone of another race. Who are the exceptions? Predictably, people brought up in more racially diverse settings, those with friends or romantic partners of another race.

And even for those who don’t live multi-culti lives, the xenophobia isn’t inevitable. It can be blunted by context. In Correll’s work, if the person with the gun or cellphone is pictured in a neutral background, whites show a shooting bias toward blacks. Use a scary background in the picture instead and the bias disappears; subjects now show equally rapid-fire judgment about whom to shoot. In the amygdala-activation studies, it matters who is pictured: White subjects don’t have amygdaloid activation when viewing a picture of, say, Bill Cosby. (When you read this literature, you realize that Bill Cosby is God’s gift to scientists doing this research.)

And here’s the most heartening news: These brain responses can be fairly easily overridden. Chad Forbes at the University of Delaware demonstrated that if whites viewed a black face while hearing loud rap music, the amygdaloid response got even bigger. But put that same face over death-metal music — associated with negative white stereotypes — and you don’t get the same amygdala reaction.

Moreover, the brain’s response to race can be overridden by re-categorizing people. As reported by Robert Kurzban at the University of Pennsylvania, subjects shown a film clip of a mixed-race crowd of people tended to unconsciously categorize people in the crowd by race. But if people in that crowd were wearing one of two different sports jerseys, subjects categorized them by team affiliation instead of by race. In other words, if the brain evolved to make automatic racial distinctions, it evolved even more strongly to differentiate between Dodgers fans and Giants fans.

Finally, work by Susan Fiske at Princeton found something else that can override the amygdala response to another race. Subjects were asked to decide whether people in the pictures they were shown would like a particular vegetable. In other words, they were asked to imagine the tastes of the people, to think about what they’d buy in a market, and to imagine them relishing a favorite vegetable over dinner. In that exercise, even if the face a subject saw was of another race, the amygdala wasn’t activated.

In other words, simply thinking about someone as a person rather than a category makes that supposedly brain-based automatic xenophobia toward other races evaporate in an instant. Maybe there’s hope for us as a species after all.

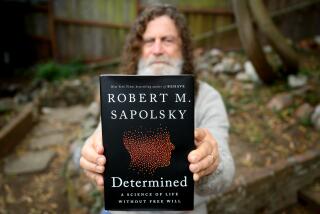

Robert M. Sapolsky is a professor of neuroscience at Stanford University and the author of “A Primate’s Memoir,” among other books. He is a contributing writer to Opinion.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.