Op-Ed: Patt Morrison asks: Pomona College economics professor and celebrity death mythbuster Gary Smith

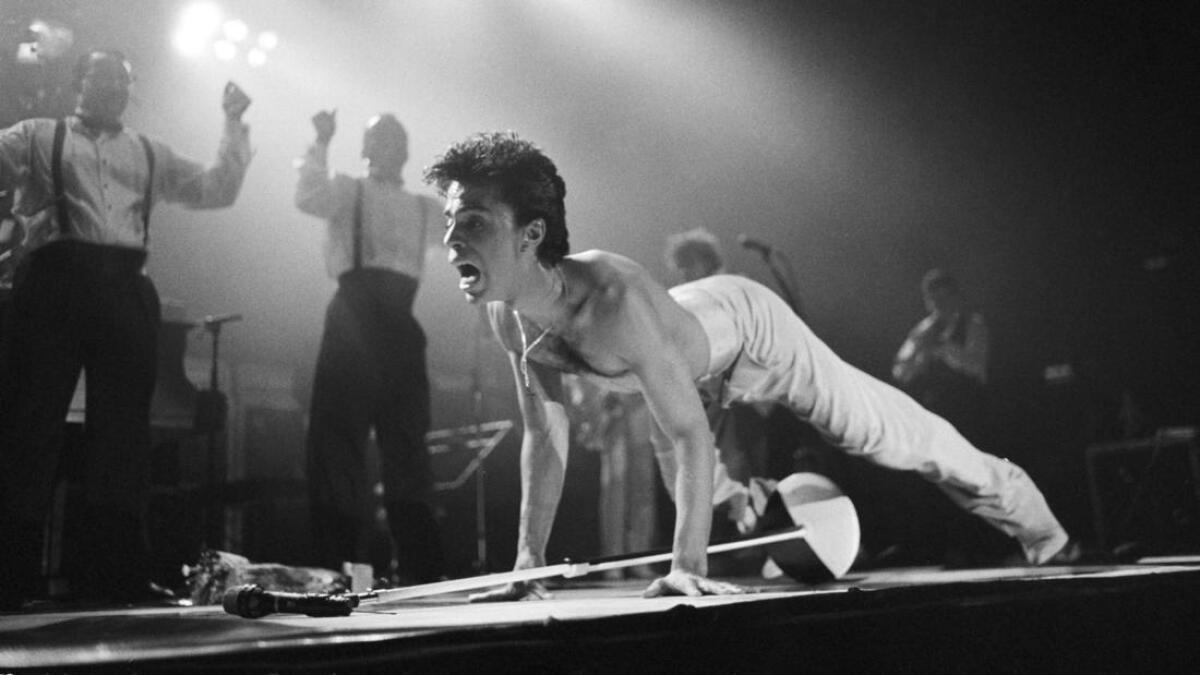

Prince performs on stage on the Hit N Run-Parade Tour at Wembley Arena in London in August 1986.

Prince was a man who not only made music but made music history, just like David Bowie, who died a few months earlier. In the absence of real information about deaths like these – and sometimes when we have real information – we humans long to see patterns even when there are none. And so sometimes we, well, just make things up. With its masses of data, the Internet should make people less credulous. But paradoxically it’s made it easier to cook the numbers to endorse just about any notion. Here’s where Gary Smith steps in. The Pomona College economics professor runs the numbers to bust the myths and debunk the mythologizers.

CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO THIS INTERVIEW ON THE ‘PATT MORRISON ASKS’ PODCAST>>

There are so many entrenched beliefs about death, especially deaths of the famous.

The thing that struck me was it started up with people talking about wow there have been a lot of celebrities who died lately, and some people even said that celebrities die in threes, which goes back to an old adage there used to be that Jesuits die in threes. Jesuits would go along and somebody died and nothing, and somebody died and nothing, and then three in a row would die, and they would say, Isn’t it remarkable that Jesuits die in threes?

When things cluster, we think something special’s going on.

And so the statistical study that went back, they got data over 40 years of Jesuit death, but it was almost exactly what you’d expect if deaths were random. It’s the same thing with people making a lot of shots in basketball, or people finding a cluster of cancer victims. Or people saying that, Isn’t it weird we had Prince die, and just a few weeks ago, wasn’t it Doris Roberts and Patty Duke, Frank Sinatra Jr.? Deaths seem to be clustering here. And there’s nothing more to it than that except it exposes the fact that our minds are not conditioned to interpret clustering as random.

A BBC story in the wake of Prince’s death began, “It now seems rare for a week to pass without a significant celebrity death being reported.” Ominous – true?

I was looking up celeb deaths of the past few weeks or so and there are a lot of people there who are called celebrities that I never heard of. There’s this female wrestler who’s also I think a porn star; I don’t even know her name but she’s counted as some kind of celebrity. I think as you expand the universe through social media, there are so many people who are so famous worldwide and famous for different things. You expand the number of celebrities of course and you are going to expand the number of celebrity deaths.

I wouldn’t put any significance to that other than the fact that the number of celebrities has been growing through the Internet, and 70,000 television channels.

The Internet is full of data; anyone can find just about anythingthere, and make it look true.

Yes. It goes back to decades ago. People did calculations by hand, it was hard to do calculations, so they thought hard before they started calculating. Nowadays the calculations are so easy; with the big computers the data are so plentiful that people go out and they massage, mangle and manipulate data to come up with all sorts of crazy theories. They make the headlines specifically because they’re provocative and they’re interesting and people say, Wow, that’s really wild. Then I look at it and it turns out what they’ve done is, they’ve tortured the data.

There’s a famous saying in economics that if you torture the data long enough, it will confess. With lots of data and powerful computers, you can just torture the data and torture the data until you find something that is provocative, statistically significant and publishable. And then maybe you get tenure, you get funding, you get on the radio, on television or in the newspapers.

And then somebody like me comes along and looks at it and finds out in fact there’s nothing there but a chance, a coincidental correlation that was uncovered by the data.

David Bowie died just a few days after his latest album was released, which for some people reinforced the notion that dying people choose to postpone their deaths until after some major milestone in their lives.

I have a friend who works in a cancer center in Cleveland and people who have terminal cancer and die the day after their wedding [anniversaries], the day after their birthdays, the day after their wives’ birthdays, the day after their kids’ birthdays -- people remember it and say, Wow, they postponed death. He went and looked at all the cancer deaths over some 20-year period, and absolutely no relationship between when people died and birthdays, anniversaries, other kind of celebrations.

It’s the same with David Bowie. There’s lots of celebrities who died on days that were not after an album, before an album was released, or after their birthday, or after their anniversary, or after Christmas or after Thanksgiving. And of course those don’t get reported.

I still remember that John Adams, the second president and one of the founders, died on the same day as Thomas Jefferson, the third president and one of the founders – and that day was the Fourth of July, 1826. Wooooh!

But then you’ve got James Madison, who died I think it was six days before the Fourth of July, so why couldn’t he postpone his death until the Fourth of July?

Does your work as a numbers mythbuster make you unpopular?

Certainly with some of the people whose myths I’ve busted! When somebody comes along and says, That’s a bunch of bull, of course that doesn’t go over well. I haven’t had any death threats about it!

I get these emails from people telling me why I’m wrong, because they know for a fact that Uncle Louie died the day after his birthday or something, one person who got a heart attack on the fourth day of the month or one person who died after their birthday. So you turn that into evidence. So I get these emails from people telling me that I’m the one who’s making the mistake.

Have people actually gotten grants and tenure and chairs as a result of this?

Oh sure. Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. It happens all the time. I was in a conference at Googleplex a few months ago. They invited in these people from all sorts of sciences, astrophysics, biology, chemistry, economics. And one of the hot topics was what they called the replication crisis.

In all these fields, somebody makes some breakthrough study and then they publish the results and they get some fame or tenure or funding or whatever. Then somebody goes out and tries to replicate it and there’s nothing there.

Carl Sagan talked about humans as pattern-seeking creatures. We see a man in the moon when there is no man in the moon. Is that what you’re up against, too, that our human instinct is to look for repetition, for things we recognize in the masses of unrecognizable stuff?

That’s definitely the case. And so with our distant ancestors, seeing patterns had some kind of survival value: if a noise in the bush often meant that there was some tiger hiding there, then you get the pattern: noise in the bush means danger.

So I think we’re genetically programmed to look for patterns, and it gives us comfort to be able to make sense of the world and not think about things as being so random.

Is it frustrating, then, to think you’re up against something we’re hardwired to do?

It is frustrating, and part of the frustration is that we can’t really do serious science without data. And these wacky theories that get published, they cast a shadow on all scientific research. That was part of the replication crisis that people talked about. It was undermining the credibility of science that so many things get published: chocolate’s bad for you – no, chocolate’s good for you; coffee’s bad for you, no, coffee’s good for you. Margarine’s better than butter; no, butter’s better than margarine. It just undermines the whole scientific endeavor.

Once you show that that kind of conclusion is bogus, how hard is it to un-ring that bell? Because Mark Twain said a lie gets halfway around the world before the truth can put its shoes on. Still true?

Still true. The idea that celebrities can postpone death, that has been refuted over and over, and yet it’s still there.

So you’re playing statistical whack-a-mole.

Pretty much.

Let’s talk about some of those specifically that you have looked at in your work. First of all, a shout-out to baseball fans, because baseball players are very superstitious. What are some of the superstitions and the beliefs of baseball players that you have found to be not true?

My son is actually a pretty good baseball player so I know a lot of these crazy theories, things like, when you leave the field, you jump over the baseline, or when you leave the field, you step on the baseline. I don’t know how you would test that kind of stuff.

And the theory that if you get into the Hall of Fame, you might as well make out your will?

There’s this great database out there that has dates of birth, dates of death and a lot of other statistics about all major league baseball players. However, for a lot of the baseball players who were not so famous, who just played a couple of years and disappeared, nobody knows exactly what happened to them or when they died. So they’re entered in this database with no date of death.

When this person did the study, that somebody was born in 1850 and now we were in the year 2000, they assumed the person was 150 years old! The baseball players in the Hall of Fame, of course, we know when they died, they’re famous, so we kept track of them.

So relative to the overall mass of baseball players, they had relatively short lives -- mainly because you had all these obscure players that were recorded with death dates that they lived to 150, 140, 120.

Methuselah Jones, who played for the Yankees, right?

Yep, 180 and still going strong!

Maybe be you should change your title to professor of gullibility science.

Sounds good to me.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.