Op-Ed: Confederates, Columbus and everyone else: Let’s just tear down all the public memorials to ‘great’ men

Columbus Day will be more than just a holiday this year. It will be a confrontation with history. In August, the Los Angeles City Council voted to erase the event from its calendar, replacing it with Indigenous Peoples Day. In September, the statue of Christopher Columbus in Manhattan’s Central Park had its hands painted blood red by vandals. Earlier this year, New York Mayor Bill De Blasio announced plans to consider removing all statues of Columbus from city property, classifying them as “monuments to hate.”

This isn’t just about Columbus — or Confederate generals or any other villain, perceived or real. By now, it has become clear: Public memorials to great men have outlived their purpose. It’s time for them all to come down.

Iconoclasm is not just an American phenomenon. It’s global. In Canada, a statue of John A MacDonald, the “father of Confederation,” struggled to find a home at his bicentenary in 2015, and this year, the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario called for removing his name from public schools, given his role in the cultural genocide against indigenous groups. In Accra, in 2016, the University of Ghana removed a statue of Mahatma Gandhi from campus, remembering his statement, made during his residency in South Africa, that Indians were “infinitely superior” to native Africans. Removing Cecil Rhodes from the campus of the University of Capetown in 2015 was less controversial.

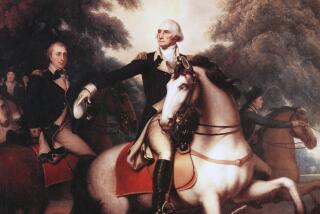

What distinguishes American iconoclasm is its chaos: statues pulled down by angry mobs or removed by officials in the middle of the night. And the chaos leads to incoherence — unobtrusive Confederates decapitated here and there, while massive tributes such as Stone Mountain remain. When President Trump and his lawyer asked whether monuments to George Washington would be targeted following those to Robert E. Lee, liberals were outraged. Lee was in no way like Washington, they claimed, and the American Revolution was in no way like the Civil War. Except that the Revolutionary War was waged by white supremacists and the Constitution entrenched their power. It was Americans, not their British overlords, who hammered out the three-fifths compromise, and black slaves were not their only victims. Washington earned the name Hanodagonyes or “Town Destroyer” among the Iroquois in New York.

When the people of the future look back on us, it is best that they have no statues to remember us. They would tear down every one.

Thomas Carlyle in “Heroes and Hero Worship” articulated the spirit that built the statues that fill our parks and our cities: “The history of what man has accomplished in this world is at bottom the History of the Great Men who have worked here,” he wrote in 1841. “All things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realization and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world: the soul of the whole world’s history.”

Carlyle’s vision has expired. The notion that an individual, any individual, can embody human ideals is null and void.

Who deserves a statue or national holiday in 2017? President Obama? A man whom Human Rights Watch described as a leader who “never really warmed to human rights as a genuine priority and so leaves office with many opportunities wasted”? Saint Hugh’s College in Oxford had to remove a portrait of Aung San Suu Kyi because the Nobel Peace Prize winner, like so many other winners, has turned out to be comfortable with mass death. Perhaps only Malala Yousafzai fits the level of innocence we now require from our political icons; she was a child when she won the Peace Prize.

When the people of the future look back on us, it is best that they have no statues to remember us. They would tear down every one. We imagine that history has progressed to the point at which we may sit in judgment over the past, but the number of slaves in the global supply chain is growing, not shrinking. Anyone who has eaten shrimp in the last five years has participated in a slave economy. Anyone who has purchased a smartphone has contributed to enslavement.

Statues to the Confederacy were consciously created to impose white supremacy as a dominant ideology. But the intention behind statues is often more muddying than clarifying of their function. Statues to Columbus were often raised to celebrate the contributions of Catholic and Italian American immigrants. The Ku Klux Klan explicitly resisted monuments to Columbus, seeing them as “part of a conspiracy to establish Roman Catholicism,” as one Klan lecturer put it.

Statues never represent the people on the monuments: They represent the interests of those who build them.

It is in our interest to take the worst thing a historical figure has ever said or done, establish it as their whole being and then make the destruction of their memory a collective benefit. This process will leave no statue standing. As Hamlet said, “Use every man after his desert, and who shall ‘scape whipping?” If Gandhi can’t survive, Columbus certainly won’t.

The reality of people in history — the mixture of good and evil, making individual choices within imposed systems, in a specific context — has no interest either for those who raise statues or for those who tear them down.

A blank at the heart of Columbus Circle where a person once stood would suit our moment perfectly.

Stephen Marche is the author, most recently, of “The Unmade Bed: The Truth About Men and Women in the Twenty-First Century.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.