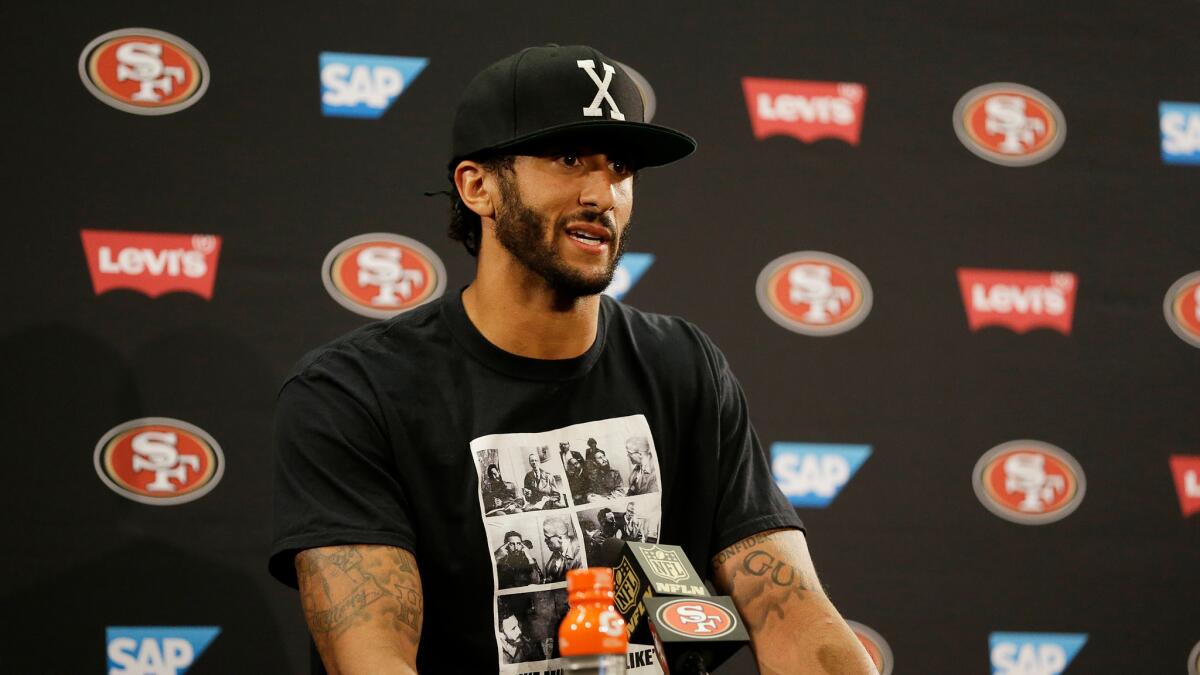

Op-Ed: Colin Kaepernick’s problem: Angry responses always drown out the reason for a protest

In the annals of athlete protests against the policies of the U.S. government, Colin Kaepernick’s decision to remain seated during the national anthem at a preseason football game ranks below Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising their fists at the 1968 Olympic Games, or Muhammad Ali’s repudiation of the Armed Forces.

Nevertheless, when Kaepernick refused to “show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,” the interconnected worlds of social and sports media threw a patriotic fit, lambasting the mixed-race Kaepernick for not supporting the troops and failing to appreciate the opportunities given him by his country. He became, for a few days at least, a pariah. All of which obscured the central issue that he stood up, or sat down, for: police disproportionately targeting and killing African Americans.

As I discovered as a boy — in circumstances far less exalted than Kaepernick’s — when you protest a symbol, the reasons for the protest will be overwhelmed, and quickly forgotten, by the angry responses to the action, or inaction, itself. Attention shifts inexorably from the issue compelling the act of dissent to the actor himself.

How many of us stand because it’s easier than staying seated, easier than offering a small protest, than publicly questioning state power?

In the 1970s, I attended Paul Revere Junior High School in Brentwood, where we were required to recite the Pledge of Allegiance to the Stars and Stripes during homeroom. One morning, in the eighth grade, I convinced my classmates not to say the pledge. It was, I pointed out, our constitutional right.

This small act of teen rebellion resulted in a very subdued pledge, which infuriated our teacher, Mrs. Maddox. She demanded to know the cause of this treason, and I was quickly singled out as the instigator. Mrs. Maddox spent the rest of that homeroom period lecturing us about the importance of patriotism and reduced our choices to saluting the flag or becoming communists. This was during the Cold War, and the latter prospect chastened my classmates, who, the next morning, dutifully stood and began, “I pledge allegiance to the flag … .”

I still refused to stand. I was only 13, but I had a notion that my staying seated was protected by the ideals supposedly embodied in the flag. This, I decided, was the very American ground on which I would fight Mrs. Maddox. (OK, I was also being a smartass.) She eagerly took up the battle, and after one more day of recusing myself, I was sent to the principal’s office, where I repeated my position. The principal listened wearily as I attempted to explain my actions. For good measure, I threw in the fact that I was Japanese American, and that Japanese Americans had been interned by the U.S. government during World War II.

I didn’t have to say anything, he told me, but I had to stand up.

The next day, I again refused to stand and was sent back to the principal’s office. At this point, the whole affair had become a spectacle for my classmates, some of whom were calling me “the flag salute guy.” My parents were summoned, and when my father, an Army veteran, arrived to meet with the principal, they had to convene in a temporary office, as the principal’s office had been gutted by arsonists. My father pointed out that perhaps my unpatriotic fervor was not that crucial an issue, considering students were setting fire to the school. In fact, the principal suggested, my silent protest was somehow connected by a continuum of malfeasance to acts of vandalism.

A temporary compromise was reached: I would leave my homeroom every morning and stand outside the classroom during the flag salute. But even that ceremonial exile was not satisfying to Mrs. Maddox, who insisted that I be transferred from her homeroom.

That effectively ended my first, and so far only act of political agitation on behalf of free speech. Miss Williams, my new homeroom teacher, was indifferent to the flag salute, occasionally even forgetting to lead us in the pledge.

It felt like a great weight had been lifted; I no longer would be publicly known for what started essentially as a prank. Because when you are the protagonist of one of these protests, as Kaepernick has been for a week now, it begins to define you in a manner that you never intended.

You stand or place your hand over your heart almost out of reflex, but then one morning, for whatever reason, you don’t want to do it. It may be a sense that this is wrong, or boring, or ridiculous or simply has nothing to do with your feelings, positive or negative, about your country. And how many of us stand because it’s easier than staying seated, easier than offering a small protest, than publicly questioning state power?

While an exhibition game is not the Olympic medal podium, Kaepernick did make a courageous decision in choosing to stay seated. That is the freedom the “Star Spangled Banner” supposedly celebrates, and that our constitution supposedly protects, for a quarterback — or an eighth-grader — for reasons as noble as protesting police brutality, or as trivial as a kid experimenting with the 1st Amendment.

Karl Taro Greenfeld is the author of eight books, including the novel “The Subprimes.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.