Column: Through fiction, veterans present a clearer truth on U.S. wars

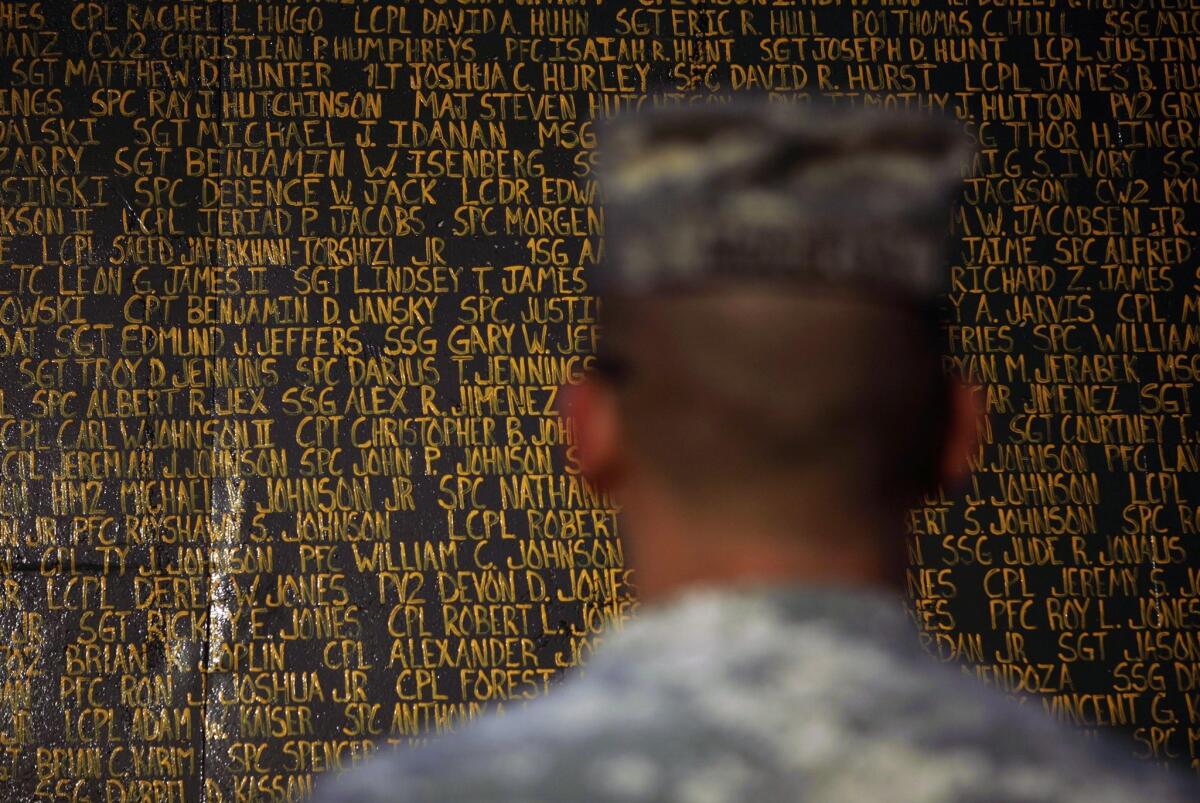

A soldier stands in front of a monument bearing the names of U.S. service members killed in Iraq since the 2003 U.S. invasion, at Forward Operating Base Warrior in Kirkuk in 2010.

Here’s a summer reading suggestion you probably didn’t see coming: Try some of the excellent recent fiction produced about America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, much of it by veterans.

Almost 14 years of combat haven’t pacified the Middle East, but at least they have produced a substantial contribution to American literature: impressive memoirs, fine novels and stories, even some significant poetry.

Our never-ending conflicts are in danger of becoming an abstraction to many civilians — even though we still have almost 10,000 troops in Afghanistan and more than 3,500 in Iraq (and that last number may climb in the months ahead). Well-made fiction, however, can sometimes make war more concrete than even the best

journalism.

Here, for example, is a soldier in Kevin Powers’ novel “The Yellow Birds,” answering a reporter’s clumsy question — the one almost every civilian asks — What’s it like?

“It’s like a car accident. You know? That instant between knowing that it’s gonna happen and actually slamming into the other car,” the soldier says. “Except for here it can last for goddamn days.”

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

War fiction: Doyle McManus’ July 5 column referred to soldiers flown to Dallas for a Super Bowl game in the novel “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk.” It was for a Thanksgiving game. —

------------

Powers, who served as an Army machine gunner in Iraq, describes a firefight as a chaos of noise and adrenaline:

“We heard bullets, sounds like small rips in the air, reports of rifles from somewhere we couldn’t see. I was struck by a kind of lethargy, in awe of the decisiveness of every single attenuated moment.”

There’s not much heroism in this generation’s war stories. Soldiers fight, bravely or not, to defend their buddies and keep their sanity, as soldiers have always done. And once the shooting is over, they can’t help wondering why they’re there.

“What are we doing?” a soldier asks a chaplain in Phil Klay’s remarkable collection of short stories, “Redeployment.” “We go down a street, get I.E.D.’d, the next day go down the same street and they’ve I.E.D.’d it again. It’s like, just keep going till you all die.”

In one story, “Prayer in the Furnace,” Klay, a former Marine staff officer, deploys a chaplain to wrestle with the problem of good and evil.

“I see mostly normal men, trying to do good, beaten down by horror, by their inability to quell their own rages,” the chaplain-narrator reflects after a corporal named Rodriguez confesses that he might have killed a civilian. “And yet, I have a sense that this place is holier than back home. Gluttonous, fat, oversexed, overconsuming, materialist home, where we’re too lazy to see our own faults. At least here, Rodriguez has the decency to worry about hell.”

What good is faith in such a place? Rodriguez asks the chaplain, who has been wondering the same thing himself.

“We are part of a long tradition of suffering,” the chaplain offers. “Do not suffer alone. Offer suffering up to God, respect your fellow man, and perhaps the sheer awfulness of this place will become a little more tolerable.... In this world, He only promises we don’t suffer alone.”

Rodriguez turns and spits into the grass. “Great,” he says.

Other worthwhile novels on the Iraq war include “Fives and Twenty-Fives,” by Michael Pitre; the bestseller “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk,” by Ben Fountain (not a veteran, but many veterans say he got it right); and, on Afghanistan, “The Valley,” by John Renehan, and “Green on Blue,” by Elliott Ackerman (which focuses, unusually, on Afghan characters, not Americans).

There’s little explicit politics in these books; soldiers and Marines in war zones don’t spend much time debating foreign policy. Many focus instead on the jarring divide between daily life at home and the grueling experience of combat overseas.

The most painful passages in “The Yellow Birds,” for example, aren’t about warfare; they’re about the protagonist’s inability to reconnect to civilian life after a troubled tour of duty in Iraq. He stumbles into a group of his high school friends on a picnic and finds himself unable to speak; he has been robbed of his youth, they still have theirs.

“I don’t deserve anyone’s gratitude,” he frets. “Everyone wants to slap you on the back and you start to want to burn the whole goddamn country down, you want to burn every goddamn yellow ribbon in sight.”

Or, to quote Billy Lynn, the protagonist of Ben Fountain’s darkly comic story about a group of soldiers flown abruptly to Dallas to serve as props at the Super Bowl:

“Somewhere along the way America became a giant mall with a country attached.... Billy can’t help but regard his fellow Americans as children. They are bold and proud and certain in the way of clever children blessed with too much self-esteem, and no amount of lecturing will enlighten them as to the state of pure sin toward which war inclines.”

These stories won’t get you all the way to knowing What It’s Like, of course.

To borrow a joke from an earlier generation: “How many Vietnam vets does it take to screw in a light bulb? You wouldn’t know, you weren’t there.”

But they’re a first step toward feeling their sacrifices in your bones. And they might help you find something more meaningful to say to a veteran than “Thank you for your service.”

Twitter: @doylemcmanus

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.