Torture in the court

Today, Carter and Korb address the legal questions surrounding the use of torture against Guantanamo detainees. Previously, they the extent to which Congress should intervene in military matters and the actions of Adm. William J. Fallon and other officers who publicly disagreed with their civilian commanders. Tomorrow and Friday, they’ll discuss the Air Force tanker contract and the kind of wars for which the military should prepare itself.

America should not torture, period

By Phillip Carter

Larry,

To ask whether we should allow evidence produced by torture to be used against suspected terrorists is to put the cart about 10 miles before the horse. America should not torture, nor should it employ any coercive interrogation means tantamount to torture, period. Our flirtation with this rule over the last seven years has done us incalculable strategic harm -- and has produced little or no intelligence of value in return.

I’m sure your officer training contained a block of instruction on the law of war, just as mine did. The rules were fixed and immutable: Don’t target civilians, don’t use unnecessary force and don’t commit war crimes, including torture. These rules partly reflected a cold calculation of self-interest. Military leaders knew that any crimes committed by American troops would be revisited on American troops if they were captured. Further, breaching these norms would undermine American strategic interests, regardless of any short-term gains. But there was more to it than that. At the very core of the American military professional identity is a strong sense of honor. We’re the good guys, and we do the right thing because we’re inherently good. We expiate the sins of warfare by acting in a just, humane and lawful manner whenever possible.

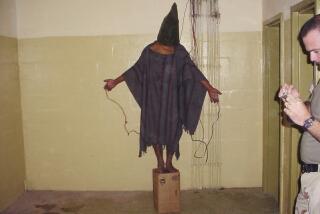

Unfortunately, our recent history is littered with grave breaches of these norms -- the My Lai massacre in Vietnam and the Abu Ghraib prison scandal in Iraq are perhaps the most famous and damaging. If Al Qaeda had hired a Madison Avenue public relations firm to build a propaganda campaign, it’s hard to imagine that it could have done a better job than we did with Abu Ghraib. These breaches prove the importance of fighting justly and honorably; we cannot afford to surrender the moral high ground to our enemies so stupidly. This is especially true for this war, often characterized as a global struggle for the hearts and minds of moderates around the world. We need to show through our words and deeds that we are the good guys.

Which brings us to Guantanamo and our country’s detention, interrogation and trial regime there. There are colorable legal arguments for the policies we have adopted; many U.S. courts have found a basis to uphold these policies. However, we should not confuse creative lawyering with smart strategy, nor should we define our nation’s interests based simply on what is legal. There are larger equities here. Simply put, we cannot afford the legal and moral cost of Guantanamo any longer. Regardless of the actual facts, the perception around the world is that America is unlawfully holding detainees there, torturing them to get information and then using that information to prosecute them before military tribunals resembling kangaroo courts.

So of course it stands to reason that we shouldn’t allow the fruits of torture into these courts. We shouldn’t be torturing in the first place. Our abdication of American moral leadership in this area ranks as one of the great strategic failures of the last seven years. It has hurt our alliances with Europe and international institutions and undermined our efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan to promote the rule of law. When will we learn?

Phillip Carter practices government contracts law with McKenna Long & Aldridge in New York. He previously served as an Army officer for nine years, deploying to Iraq in 2005-06 as an embedded advisor with the Iraqi police in Baqubah.

An easy answer muddled by this administration

By Lawrence J. Korb

Phil is correct to say that torture in any way, shape or form by any agent of the U.S. government -- including private contractors -- is not only wrong but counterproductive and should not be admissible as evidence against a defendant. In theory, every political, military and diplomatic agent of the U.S. government would agree with that. The real issue is agreeing on what constitutes torture.

This situation is illustrated by two issues -- first, whether the entire federal government should follow the Army Field Manual, which outlines, for military personnel, what constitutes torture. The manual says that waterboarding does in fact constitute torture. When Congress passed a bill that would have completely outlawed waterboarding, President Bush vetoed it. Even Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), the presumptive Republican presidential nominee who had been a leader in getting the U.S. to renounce torture, supported the president.

The second issue involves defining what actually constitutes torture. According to a memo drafted by then-White House Counsel Alberto R. Gonzales, who went on to become attorney general, almost anything short of murder is not torture. When Gonzales resigned as attorney general, his replacement, Michael B. Mukasey, also refused to say whether waterboarding constitutes torture. Therefore, if the person lives through the interrogation, he or she by definition has not been tortured, so anything gleaned from the interrogation can be used.

Phil mentions Abu Ghraib and My Lai and the harm those two episodes have done. These were certainly horrible events that hurt our reputation around the globe. But these incidents resulted not just from negligence on the part of these soldiers’ commanders; they also resulted from placing soldiers in situations for which they were not prepared. The soldiers at Abu Ghraib were Reservists with little or no background in interrogation, and Army Lt. William Calley, the soldier court-martialed for My Lai, was an Officer Candidate School graduate sent to Vietnam without adequate training.

Guantanamo is another case entirely. When former Secretary of State Colin Powell was asked last year when the detention center at the base should be closed, Powell answered, “This afternoon.” Guantanamo is a textbook case of the end not justifying the means. It is a result of the climate created by an administration that has overreacted to 9/11 so much that it has tarnished nearly 250 years of American tradition.

Phil concludes with the lament from the Vietnam era, “When will we ever learn?” I am afraid that we will have to wait until a new administration.

Lawrence J. Korb, assistant secretary of Defense in the Reagan administration, is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and a senior advisor to the Center for Defense Information.

| | Day 3 | |

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.