Editorial: What makes a good school?

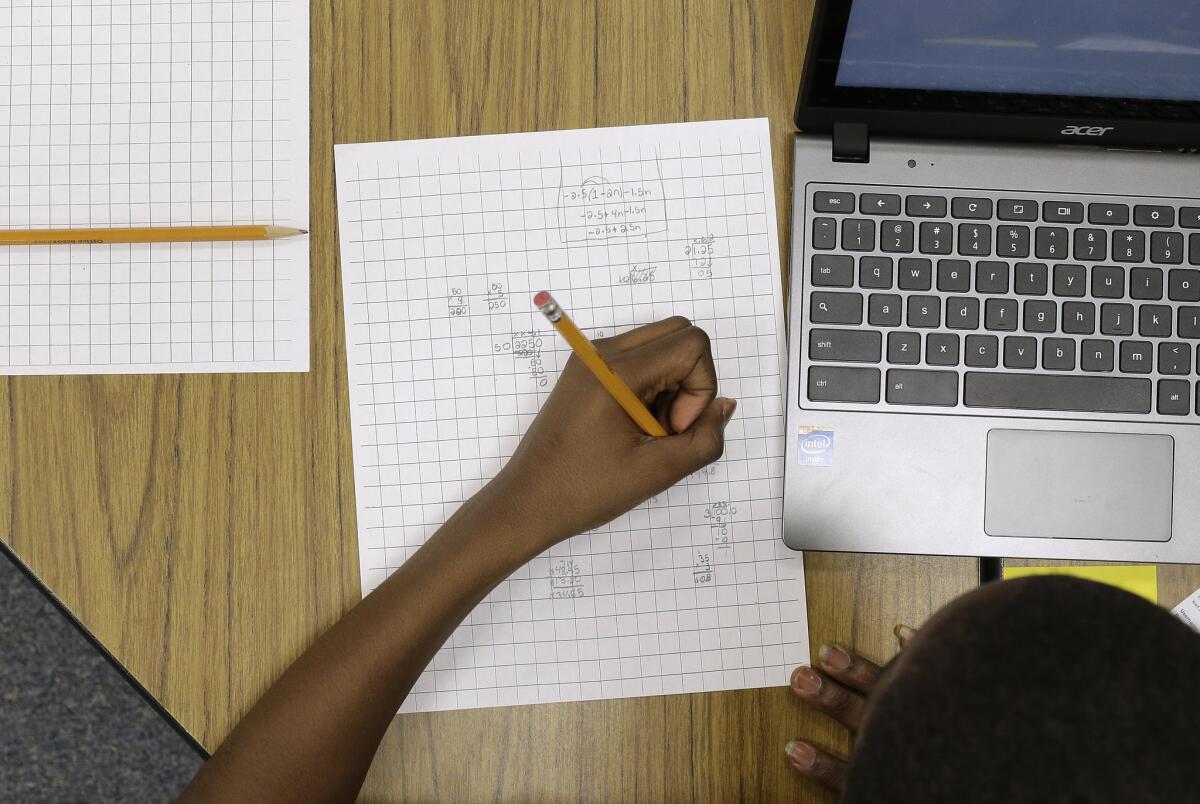

Yamarko Brown, age 12, works on math problems as part of a trial run of a new state assessment test at Annapolis Middle School in Annapolis, Md.

California was way ahead of President Obama in asserting that it takes more to measure the quality of a school than merely looking at its standardized test scores. In fact, in March, the state suspended what is known as the Academic Performance Index, the measure by which schools are judged in the state, saying it was time for a “re-set” and an overhaul. But now the question is: What exactly should the new measurements take into account?

The state Board of Education is scheduled to discuss what a new school accountability system might look like at its meetings Wednesday and Thursday. Under a 2012 state law, at least 40% of any new rating must consist of factors other than the scores of the school’s students on standardized tests (in this case, the new Common Core-aligned tests). Some possibilities: graduation rates, the number of students who leave high school having met the requirements for entry to a four-year college and the speed with which children who don’t speak English become fluent. Other ideas involve more subjective factors: a school’s “climate,” the social and emotional education it offers or its efforts to involve parents.

The test-based scores were simple and clear to parents, the public and to schools themselves.

The board doesn’t have much time to pull all of this together. The new standards are supposed to be in place in the spring, and schools still don’t know what their primary measures of quality and improvement should be. But there are troubling indications that the board might adopt a system that would do a poor job of holding schools accountable. There’s talk of having no overall score at all but rather providing data on a variety of disparate measures, and leaving it to local school districts to do the policing.

The state was wise to call for a broader view of what makes a good school, but it also should remember what was good about the old API scores and strive to keep that.

The test-based scores were simple and clear to parents, the public and to schools themselves. They allowed people to see how much a school improved — or didn’t — year to year, and how close it came to overall proficiency, as defined by the state. They allowed parents to see how their school was doing compared with others. The API included clear goals: 800 was considered the marker of proficiency, with interim improvement targets along the way.

And it measured outcomes based on the data. The scores didn’t reflect how hard schools tried, whether parents were involved or whether students’ emotional intelligence was being cared for, but how well they were learning, at least as measured by the tests.

Obviously, some of that simplicity will be lost in a system that takes a more rounded look at school achievement. But the school board should keep this as clear and performance-based as possible. Parents and the public have the right to know whether students are mastering their schoolwork at each school, and when and how the state will intervene when a school fails to improve year after year.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.