Editorial: Campaign 2016: GOP plans to repeal Obamacare won’t bring the change you’re hoping for

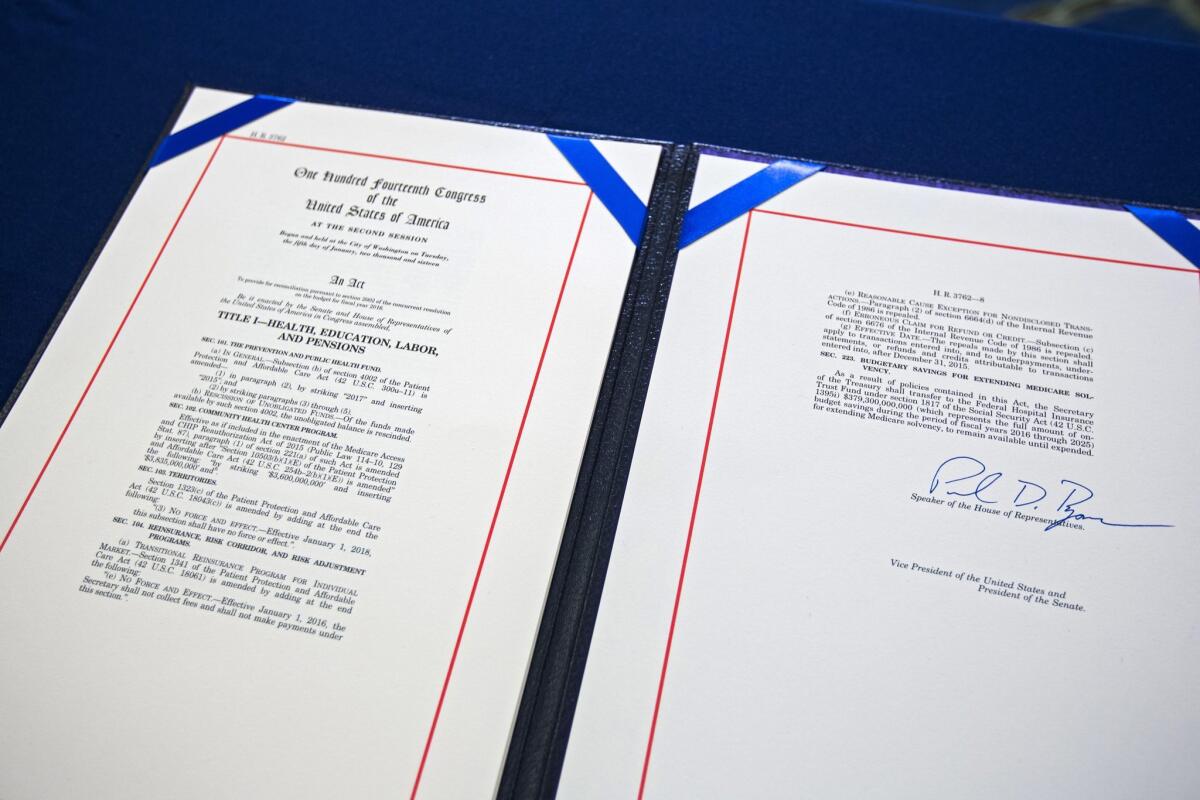

A bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act, signed by Republican Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, is seen in Washington on Jan. 7.

For the third time in eight years, the presidential campaign is doubling as a referendum on the U.S. healthcare system. And once again, the debate will revolve around the rising cost of health insurance and the number of people struggling to obtain or maintain coverage. The obvious difference this time, though, is that the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare, is now fully in effect.

Although the 2010 law has helped slow some cost increases, the continuing rise in premiums and prescription drug costs and the uptick in healthcare spending growth show that there’s much work left to do. The question for voters this year is whether that work would be easier if the Affordable Care Act were repealed, and the answer is no.

It’s important to remember that healthcare costs were rising rapidly from 2000 to 2008, when double-digit premium increases were common in both individual and group plans. Nevertheless, all the major GOP candidates in 2012 and 2016 have suggested that we roll back the clock to the pre-Affordable Care Act days, when insurers were free to reject or gouge enrollees with preexisting conditions, and to exclude coverage for less common, more costly ailments.

To protect consumers and slow healthcare cost growth, Republicans Donald Trump, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio have united behind two proposals.

The first is to let insurers offer policies across state lines. That’s a solution in search of a problem, however, because health insurance is by its very nature a local product, not a national one. To serve consumers in Los Angeles, insurers have to line up a network of doctors in Los Angeles; it does them no good to offer Angelenos access to a network in Sioux City, no matter how low the cost.

Meanwhile, hospital and physician groups are consolidating, giving them more power to dictate prices to whatever insurers happen to serve their region. That’s a problem no candidate is discussing.

The second GOP idea is to lower the cost of high-deductible plans, which encourage consumers to become smarter shoppers for healthcare services. That may be a good idea, but it’s no panacea. Not only do consumers often need healthcare on an urgent basis — one doesn’t shop around for an ambulance service — but they lack the sort of comparison-shopping tools they rely on for most every other good they buy. Medical professionals are slowly developing ways to measure the quality of a doctor, hospital or treatment, but those efforts are in their infancy.

On the other side of the political spectrum, socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders wants to eliminate private insurers and extend Medicare to all Americans — an idea with great appeal among liberal Democrats. Sanders argues that the government’s lower overhead would result in huge savings. But simply cutting administrative expenses wouldn’t address the incentives within the industry that are raising costs relentlessly. His plan is like a proposal to hit the brakes on a runaway train without trying to unstick the accelerator.

The inevitable result would be the government having to choose whether to pay for less care — a.k.a. rationing — or spend ever more on healthcare.

What we really need is to fundamentally change the way healthcare is delivered and paid for. A system built to profit from sickness and injury has to be reoriented to profit from wellness and prevention. We also need far better ways to measure the value we’re getting from the money we spend, so that we can shift dollars away from less effective and efficient providers, drugs and devices.

The industry has been exploring those sorts of changes for a while, but the Affordable Care Act accelerated the efforts. Its insurance reforms and subsidies also have helped cut the percentage of uninsured Americans from 16% in 2010 to 9.1% through the first nine months of 2015.

Yes, the increase in coverage has come at a considerable cost — $85 billion a year and climbing. But having more people insured is key to shifting care to better managed and more efficient means. In other words, it’s an essential part of the broader effort to rein in healthcare costs — and eliminating it would be a step backward, not forward.

This is one in a series of editorials on issues in the 2016 presidential election.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.