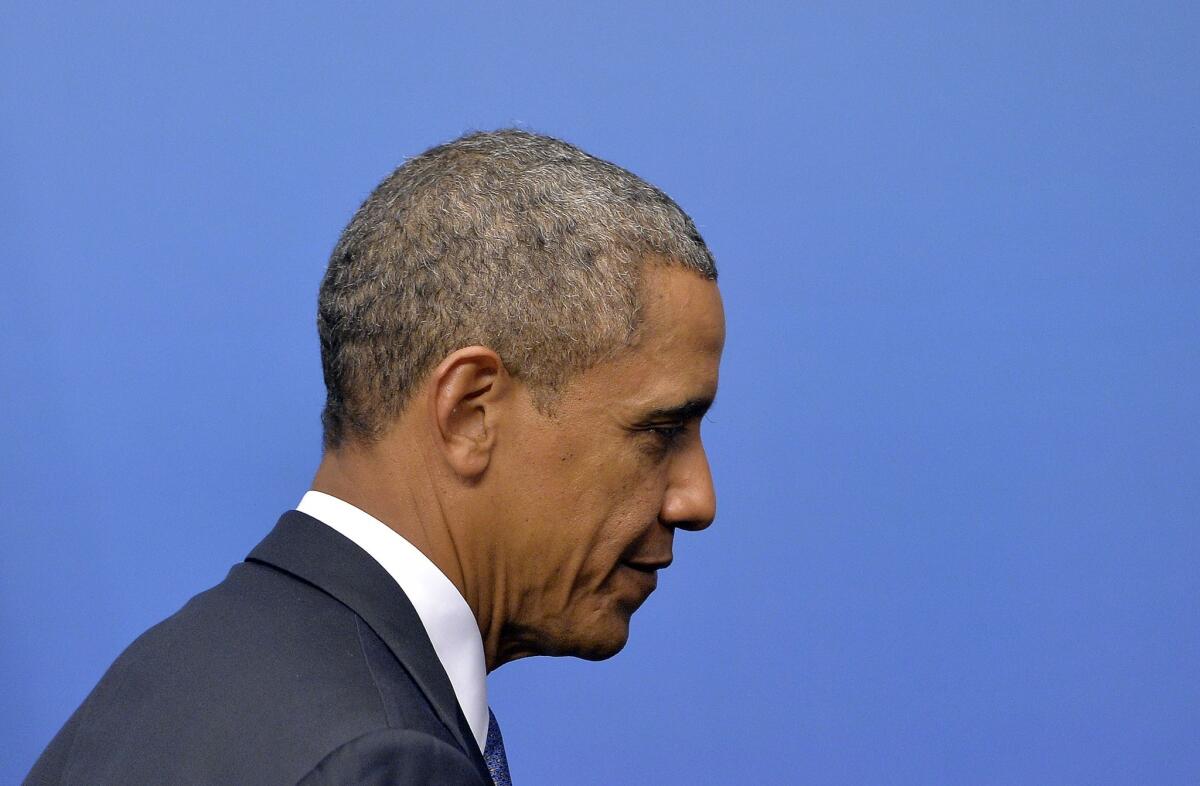

As Obama hesitates, Israel worries

President Obama has repeatedly and publicly declared that the United States will not allow Iran to acquire nuclear weapons; he has, apparently, promised Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as much. While he has not explicitly declared that the United States will employ military means if all else fails, a succession of senior American officials has stated that all options are “on the table.”

In part, these declarations were prompted by a fear that, once diplomacy and sanctions were perceived in Jerusalem to have failed, Israel would go it alone and launch military operations against the Iranian nuclear project, sucking in the U.S. and risking a wide Middle Eastern conflagration.The American assurances were designed to staunch Israeli fears and give diplomacy and sanctions more time.

But as Obama has waffled on Syria, he has convinced most Israelis that there is no depending on Washington to pull the Iranian nuclear chestnut out of the fire. Israel will have to take out the Iranian nuclear installations itself — or learn to live with a nuclear Iran led by a fanatical Islamist leadership that seeks Israel’s destruction.

Israeli officials have carefully avoided expressing these thoughts during the last few days; Israel continues to need Obama and American goodwill in a whole range of contexts. But most Israelis, to judge by comments in the media and by the man in the street, have despaired of Obama and the America he leads. Israel is alone (and, some might say, as the Jews of Europe were alone during the Holocaust).

Obama has enviable intellectual and moral qualities. But during the last weeks, he has displayed muddled thinking and a clear lack of leadership and resolution. A year or so ago, he drew a line over the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government. Since then, U.S. intelligence counts nine such attacks, according to news reports in Israel, culminating in the Aug. 21 attack that killed an estimated 1,400 Syrians, more than 400 of them children. And the United States has done nothing except talk.

Indeed, at first the talking appeared to be geared toward justifying an imminent military strike against Bashar Assad’s assets, to degrade the Syrian president’s ability to launch poison gas attacks and to deter him from resuming this form of warfare.

Then came Obama’s Saturday speech, providing for a delay — of a week, two weeks, more? — and calling for congressional endorsement of the prospective military strike. As the Constitution arguably allows a president, as commander in chief, to order limited strikes without such endorsement, many around the world have interpreted Obama’s move as a failure of will rather than keen democratic scruples.

Both Secretary of State John F. Kerry (explicitly) and Obama (implicitly) have mentioned Israel and Iran in arguing in favor of a strike: Kerry refers to America’s “credibility” with its allies and enemies; the president talked of the need to confront a “world of many dangers.”

But Obama’s Saturday announcement sent a contrary signal: Clearly, he and America are irresolute and hesitant about launching a short, limited strike against Assad’s government, and they can be expected to be much more irresolute and hesitant when it comes to tackling the far greater threat posed by Iran’s nuclear project. That could require a weeks- or months-long campaign against a more powerful enemy than Assad’s Syria and might involve the United States in extended challenges around the globe, given Iran’s allies in the Middle East and its terrorist proxy networks around the world.

The administration’s spokesmen have been careful to declare that the president could launch a strike against Assad even if Congress voted against taking action. But this is probably hogwash. Having called on Congress for endorsement, as Prime Minister David Cameron did with Britain’s Parliament, does anyone seriously expect Obama to strike Syria if Congress votes no (a vote that reflects current U.S. public opinion)?

No matter how Congress votes, Obama’s maneuver has clearly signaled Jerusalem that, at the very least, Obama can be expected to vacillate when it comes to the Iranian nuclear installations, and to turn to Congress then as well — and Congress, one may assume, will be even more chary to issue a green light, given the far greater challenges posed by the Iranian issue. Israel’s political and military leadership has surely come away from Obama’s Hamlet-like zigzagging with a sense of shock and, even more important, with a sense of isolation in the Iranian context — one that won’t disappear, even if the U.S. finally delivers a slap on the wrist against Assad.

By most counts, Iran, if not stopped, will have nuclear bombs in the course of 2014. Diplomacy and sanctions have failed over the last decade. In “negotiating” with the West, Iran has simply bought more time for its centrifuges to produce a growing stockpile of enriched uranium. In a few months’ time, Israel will face its hour of truth — and it will face it alone.

Sadly, we have seen Obama’s mettle; we will shortly see Netanyahu’s.

Israeli historian Benny Morris is the author, most recently, of “1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.