Gloria Molina, Chicana who blazed paths across L.A. politics, dies

Gloria Molina, the daughter of working-class parents and an unapologetic Chicana who transformed the political landscape of Los Angeles, died Sunday night after a three-year battle with cancer.

Her death at her home in Mount Washington, surrounded by her family, was confirmed in a Facebook post on Molina’s official account. She was 74.

Molina’s political life had been a series of firsts that inspired generations of women and Latinos to seek public office — the first Latina Assembly member in California, the first Latina on the Los Angeles City Council, the first Latina on the L.A. County Board of Supervisors.

Through her rise, Molina strode through L.A.’s corridors of power with an outsider’s skepticism and an insider’s know-how. A populist equally informed by the Chicano and feminist movements and the immigrant ethos of her parents, Molina’s battlegrounds were many.

In Sacramento, she confronted politicians who sought to dump prisons and polluters in her Eastside district. On the City Council, she spearheaded efforts to build affordable housing and have street sweepers clean neighborhoods neglected for decades by local officials. As a supervisor, she successfully pushed back against public employee pension spikes and work perks, like a private chef and personal driver for the supervisors.

Fernando Guerra, director for Loyola Marymount’s Center for the Study of Los Angeles, described her as a “perfect convergence” of communities — women, Mexican Americans, the Eastside — long ignored by L.A.’s power brokers, often both white and male.

“Even though she was part of the system,” he said, “she never gave up on the fact that you should never take its word for granted.”

Molina relished any opportunity to antagonize critics — and there were many over a 32-year political career.

After announcing she has terminal cancer, Gloria Molina reflects on her career as a trailblazing Latina politician.

Bigots wrote nasty letters that Molina insisted staffers tack onto pin boards in her office. Department heads and their employees snickered that hot flashes provoked her pointed queries during board meetings. She consistently defied Eastside politicos who tapped into her organizing smarts for their earliest electoral victories but wouldn’t support Molina once she decided to run for their seats.

“At some point, the train is going to stop and people are going to say, ‘Gloria, what have you done?’” one of them told The Times in 1993. “‘What’s the agenda? What are the solutions? What’s the program? Are we better off as a result of you being in office?’”

Former Supervisor Mike Antonovich, a frequent target of Molina’s sharp stares and sharper tongue, once described her style as “governance by tantrum.” He was one of dozens of L.A. political and cultural heavyweights — past colleagues, former foes, longtime admirers and lifelong friends — who reached out to Molina in person, via phone calls, or through passed-along messages to pay their respect after she announced her cancer diagnosis in mid-March.

“It’s not like there was a red carpet laid out for her,” said Supervisor Kathryn Barger, who got to know Molina while she worked for Antonovich. “There was a lot of challenges. It seemed like every time there was an issue, it was a constant fight, but no one did it better than Gloria.”

“Sometimes she was wrong, but most of the time she was right,” said Zev Yaroslavsky, who served alongside Molina on the City Council for four years in the 1980s and 20 years on the Board of Supervisors. He still bundles up in a quilt she knitted for him when the two were termed out in 2014. “And the reason why so many were annoyed by her was because she held up a mirror to ourselves.”

That style made her a living legend to the voters and volunteers who helped her win elections again and again.

Once, Yaroslavsky drove around his native Boyle Heights with a staffer and stopped at a former synagogue that had turned into a Latino evangelical church. The pastor approached the two, and wasn’t impressed when Yaroslavsky introduced himself as a supervisor. Then he mentioned that one of his colleagues was Molina.

“And his face lit up,” Yaroslavsky said. “County supervisor meant nothing to him, but Gloria Molina? That was everything.”

In the last weeks of her life, public and private entities that reflected the breadth of her career publicly honored the política.

Metro’s board of directors voted to name a Gold Line station in East L.A. after Molina, who fought for years to ensure that the region’s light-rail system extended to the Eastside. The all-female Board of Supervisors — each sporting a clipped-on lock of purple hair in honor of the women’s predecessor’s signature fashion flair — announced they would rename downtown’s Grand Park to reflect Molina’s crucial role in its creation. Casa 0101 in Boyle Heights christened its performance space the Gloria Molina Auditorium in honor of the frequent patron and donor to Latino arts across the Southland.

And the L.A. County Fair announced that starting this year, the winning quilt in its annual Home Arts contests would receive the Gloria Molina Quilting Award, to commemorate a lifelong enthusiast who applied the craft’s skills to her public service: a smart use of color, a methodical approach, an expansive outlook and a thick skin able to weather the pricks that came with the job because she could dole them out even better.

***

Gloria Molina was born in 1948 to Concepción and Leonardo Molina, a homemaker and construction worker with roots in the town of Casa Grandes in Chihuahua, Mexico. The family lived in a small house behind a mercadito that her godmother owned in Barrio Simons, a neighborhood in what’s now Montebello that stood next to one of the biggest brickyards in the world.

“Even though we were poor, I was never at home ever felt to be poor,” Molina said in a 2017 interview for Cal State Fullerton’s Center for Oral and Public History. “And never told I was poor. Never told that I was not going to be able to do what I wanted to do.”

As the oldest of 10 children, Molina found herself negotiating from a young age. She translated for her Spanish-speaking father, helped her mother raise her siblings and argued on behalf of them to her parents once they came of age. One incident in particular hinted at the person Gloria would become.

One day, Concepción took her children to a Lerner department store in downtown to buy clothes for the school year. The family stood at the checkout counter for 15 minutes before a pre-teen Gloria asked the store manager why they weren’t being helped. The man made a crack about her Mexican mother having so many children when he finally attended to them. Concepción told Gloria not to tell her father, but Gloria did. An enraged Leonardo went back to Lerner to square up the bill, and the family never shopped there again.

“The prejudice we saw was in small ways,” said Gracie Molina, Gloria’s sister, “but she would keep that in her mind and backbone.”

The family moved to Pico Rivera when Gloria was in third grade, joining the thousands of Mexican Americans who left the Eastside for L.A.’s middle-class suburbs. But in 1967, Leonardo suffered a work injury that put him on disability for two years. Molina effectively became the family breadwinner, working as a legal secretary for a downtown firm while studying fashion design at Rio Hondo College, then East L.A. College. At the latter school, she participated in the Chicano activism that was sweeping the American Southwest.

Molina volunteered at the nearby Maravilla housing projects, where the squalor that young women and their children lived in shocked her. She skipped a history final exam to show solidarity with the thousands of high schoolers across Eastside schools who walked out for better conditions during the 1968 “blowouts.” She was also there at the 1970 Chicano Moratorium, a protest against the Vietnam War in East L.A. that ended with sheriff’s deputies brutally beating up attendees and the deaths of three people, including L.A. Times columnist Ruben Salazar.

But it was a movie Molina saw at East L.A. College that forever changed her political outlook: “Salt of the Earth,” a 1954 film about a real-life New Mexico zinc strike in which Latinas replaced their jailed husbands on the picket lines. Their bravery resonated with Molina, who was already chafing at the sexism in a Chicano movement that claimed to be progressive.

“The guys would just kind of roll all over us,” she said in an interview with The Times shortly before her death. “And as Chicanas, we didn’t think that was appropriate.”

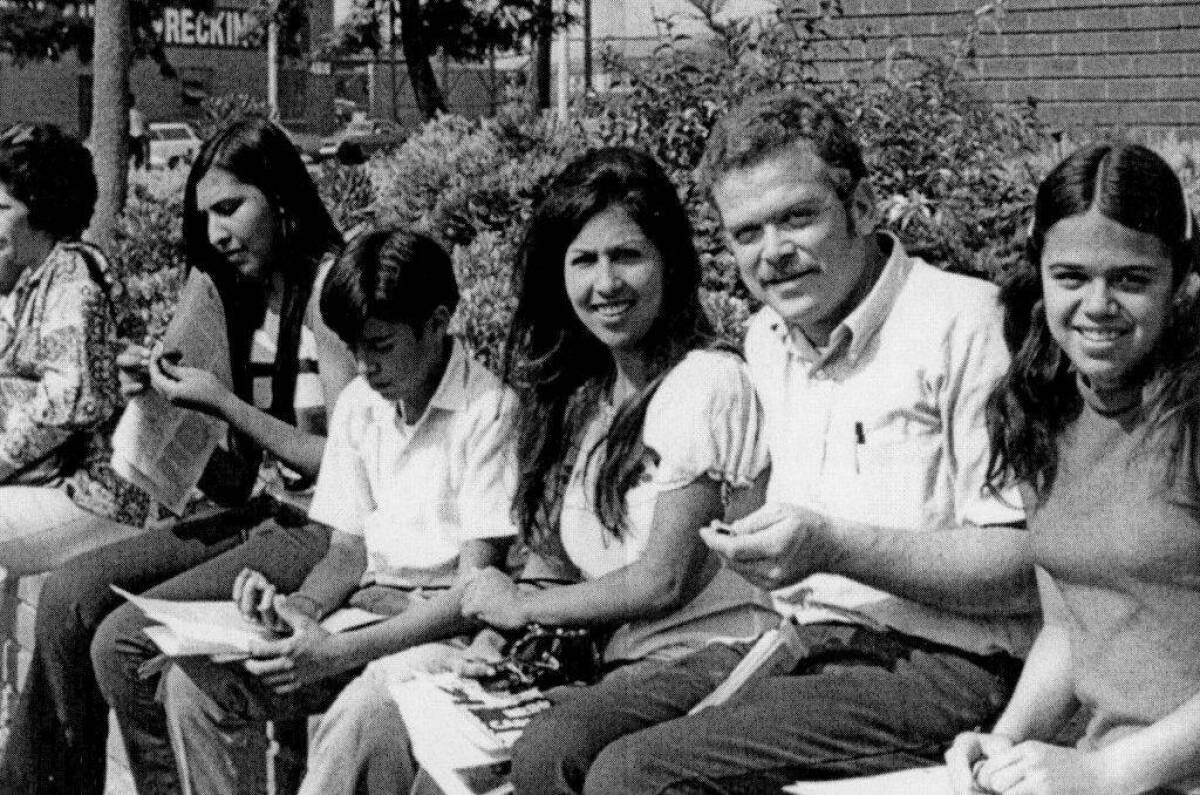

Molina nevertheless assisted on the campaigns of Richard Alatorre and Art Torres, two Eastsiders who became Assembly members in 1972 and 1973, respectively, and became the architects of a political machine that ruled the region for decades. Torres hired her as his administrative assistant — the first Latina to hold such a position in the California Legislature.

Shortly after, she became the chair of the Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional, a statewide grassroots network. It was in that role that Molina found herself sitting next to a tearful Dolores Madrigal at a news conference in 1975 announcing a class-action lawsuit alleging that L.A. County-USC Medical Center had coerced Mexican American women into sterilizations.

Antonia Hernandez, who had just graduated from UCLA’s law school, had asked Comisión Femenil just weeks before if it could be the lead plaintiff.

“I had to explain to them that if we lost the case, we could be liable to pay the defendant’s case. so the victims wouldn’t have to incur any legal costs in case they lost,” said Hernandez, who recently announced her retirement as president of the California Community Foundation. “My first impression of [Molina], then and now, is just a gutsy person, with a real sense of community obligation, and she rallied those folks” to sign on.

As the sterilization case went through the courts — a federal judge ultimately ruled against the plaintiffs — Molina served as a campaign manager or a fundraiser for Chicana candidates across California. In Los Angeles, Molina became a bridge between the separated sisterhoods of the Westside, South L.A. and the Eastside.

“We considered her the leader,” said Rep. Maxine Waters, who met Molina when she was chief deputy to L.A. Councilmember David Cunningham Jr. and leaned on her support during Waters’ successful 1976 Assembly race. “She was settled, she was cool. Without the men, she organized the women.”

While Molina campaigned for Waters, she also headed Latino outreach in California for former President Carter. She joined his administration’s Office of Presidential Personnel, tasked with diversifying the ranks of thousands of commission seats. But the lack of Latinos in Washington, D.C., made Molina yearn for home, so she took a job with the Department of Health and Human Services’ office in San Francisco, then became the L.A.-based deputy for Assembly Speaker Willie Brown.

In 1982, her former boss Torres suggested she take his Assembly district seat since he wanted to run for the state Senate. She went to seek the blessing of Alatorre, who told her to stand down: He and other Eastside leaders had decided that the seat should go to his childhood friend Richard Polanco, whom Molina remembered as a teenage boxer hanging with the wrong crowd back in the Maravilla housing projects.

Feeling betrayed, Molina nevertheless announced her candidacy.

The first-time candidate enlisted the network of women she had helped over the years as “lickers and stickers” — volunteers who phone-banked, walked precincts, sent out mailers and counted for an estimated 70% of the contributions she received, including a $5,000 check by Waters that was Molina’s first big donation.

She beat Polanco in the primary by a 52%-48% margin, then easily won the general election against a Republican opponent. Molina’s election night party was held at Stevens Steakhouse in Commerce, the restaurant where the Eastside machine had met months earlier to settle on Polanco as their candidate.

“They were accustomed to the role they played: Big chingones [badasses], they’re in charge,” Molina told The Times in 1993. “They didn’t want some pipsqueak like me coming in.”

It was a template for victory she would repeat.

In Sacramento, Molina immediately clashed with a macho world where decorum and deal-making ruled. During a budget debate between Waters and a Republican assemblywoman, Assemblymember Lou Papan cracked, “Mr. Speaker, could we keep the girls from fighting on the floor?” Molina cut in and demanded he apologize to all women. A recess was immediately called, and colleagues told Molina she should apologize to her senior colleague. She refused.

“He had to take the consequences of what he said,” Molina said in her Cal State Fullerton oral history. “You don’t just blurt out these statements without any responsibility to them.”

Soon, she would find herself pitted against state leaders on a far bigger issue back home.

The Legislature had passed a bill that required the state to build a prison in L.A. County before any other prison could open. Gov. George Deukmejian’s office chose a location across the L.A. River from Boyle Heights and secured the backing of Mayor Tom Bradley.

The Eastside exploded in opposition. Father John Moretta, pastor at Resurrection Church in Boyle Heights, first met her at a meeting at the prison’s proposed location.

“She was short, but that didn’t stop her from being tall in the eyes of the people,” said Moretta. “She was like a commander of the troops down below, and the people followed her.”

Molina politicked in Sacramento and marched in Los Angeles. She and Torres worked to have the Assembly kill the plan at the end of the legislative session in 1985. But Speaker Brown revived the plans a few months later after Molina defied him by supporting an Assembly candidate.

Soon after, Deukmejian’s office called her with a deal: Let the prison go through, and the governor would sign Molina-authored bills that sought to prevent high school dropouts. She declined, despite pleas from staff members that the benefit of those bills outweighed any harm the prison might create.

Deukmejian vetoed them all. But the Eastside prison was never built.

After announcing she has terminal cancer, Gloria Molina reflects on her career as a trailblazing Latina politician.

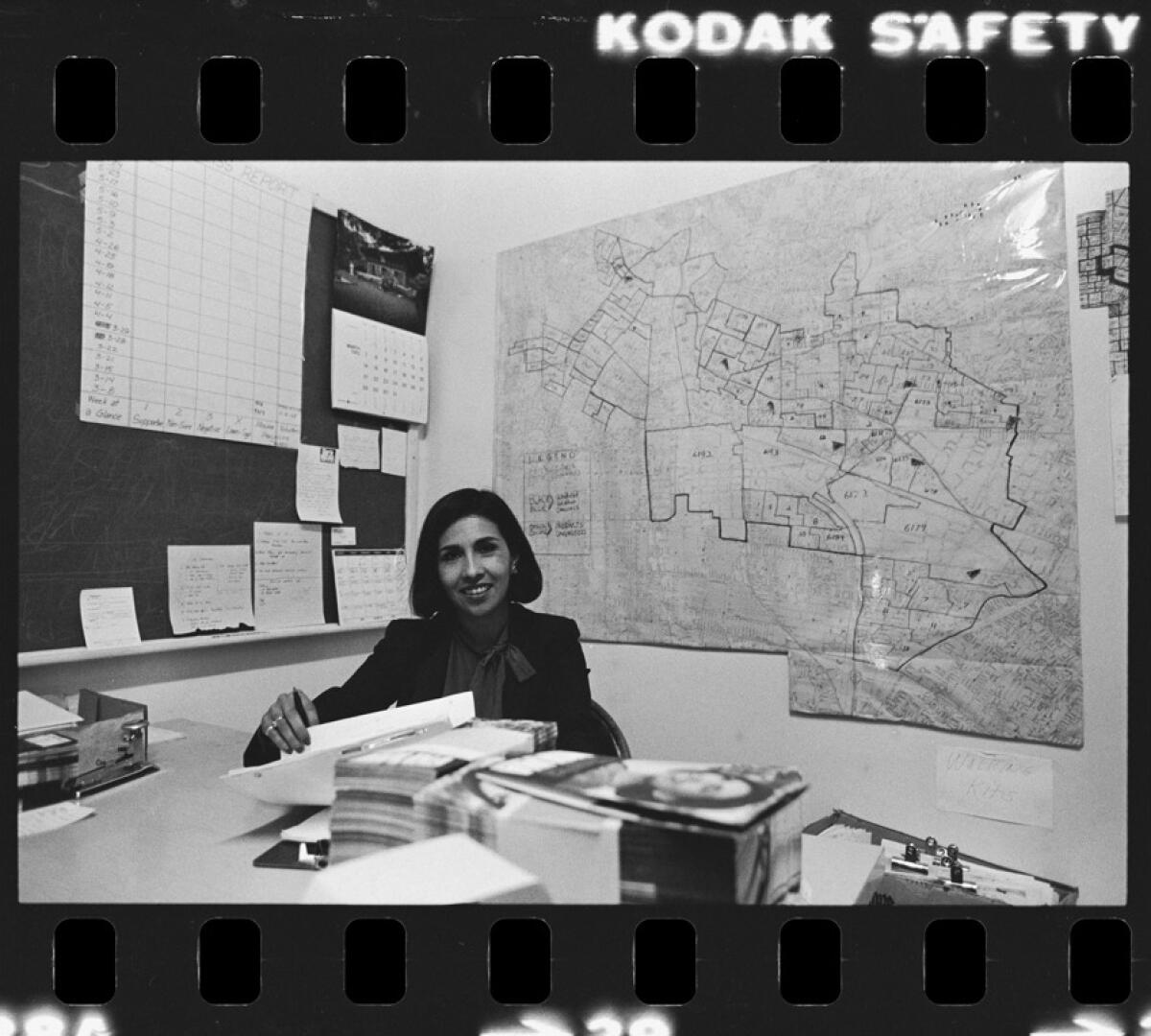

While the standoff continued, a U.S. Justice Department civil rights lawsuit forced L.A. to redraw its council districts to make it easier for another Latino candidate to win on the Eastside. Molina returned to Alatorre and Torres, and asked if she could join the former on the City Council.

Once again, Torres and Alatorre already had a candidate: L.A. Unified School District trustee Larry Gonzalez.

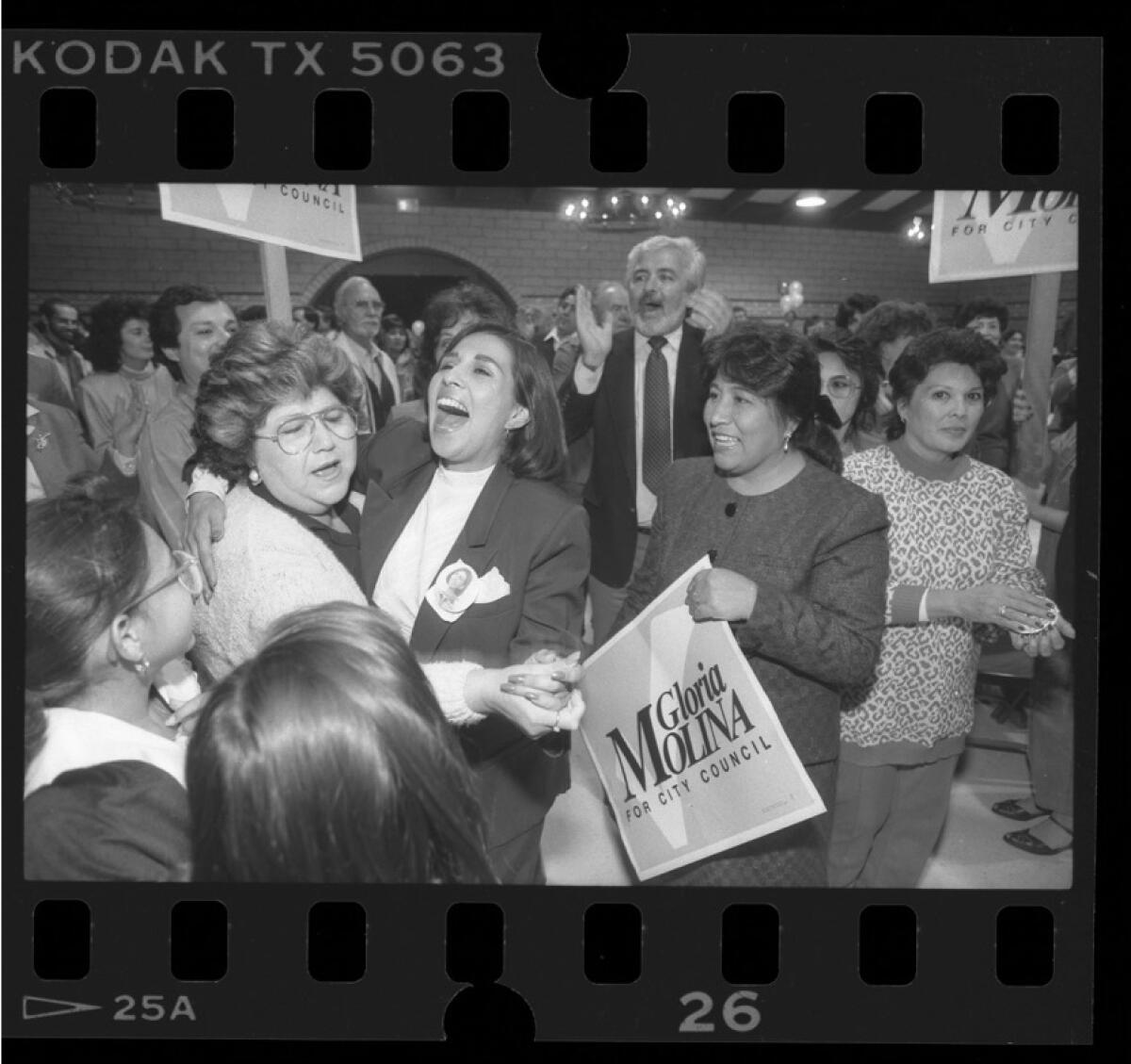

Once again, Molina went against them.

She got married during the campaign, took a two-day honeymoon, then got back to canvassing. Molina easily beat Gonzalez and two other candidates, becoming the first Latina on L.A.’s City Council in 1987.

Molina had served in her new role just a year and a half before the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund filed a lawsuit that alleged L.A. County supervisors had gerrymandered districts in 1981 to ensure a Latino couldn’t join their board. The lead lawyer was Hernandez, who befriended Molina since the unsuccessful sterilization lawsuit they pursued together a decade earlier.

This time, they would win. The 1st Supervisorial District’s boundaries were redrawn, and longtime Supervisor Peter F. Schabarum decided not to seek reelection. Molina once again went to her Eastside elders. This time, she came armed with the endorsements of Reps. Ed Roybal and Esteban Torres. But Alatorre and Torres once again refused to support her; Torres wanted the seat as well.

The two placed first and second in the primary, then moved on to a bitter general election. She became the first Latina on the board in 1991, and the first Latino since Francisco Machado and Francisco Palomares served in the 1870s.

No matter who wins today’s special election in Los Angeles County, voters in the 1st District will make history.

So many people attended her swearing-in ceremony that the crowd spilled onto the sidewalk and heard via speakers Molina declare, “We must look forward to a time when a person’s ethnic background or gender is no longer a historical footnote.”

The new supervisor joined during a fiscal crisis. She quickly earned a reputation as someone who demanded answers from all levels of the county’s departments and didn’t care for niceties.

Alma Martinez, Molina’s longtime chief of staff who met her future boss as a high school volunteer for the Carter presidential campaign, remembered how Molina had staffers shadow fancy cars that drove into the Westlake neighborhood to buy drugs. When they traced the license plates back to the parents of USC students, Molina sent them a letter letting them know what their children were up to. Another time, she printed out a list of probation officers who hadn’t worked in a while and called each of them at home, demanding they show up.

“We told her, ‘You gotta stop doing that,’” Martinez said. “She wouldn’t listen, especially when she felt something was wrong.”

The Times described her style of questioning at board meetings as “direct, abrasive, rude and unrelenting.” She offered stern words in a ringing voice as she glared at whoever was at the dais with her glasses either on the bridge of her nose or on her head. One department head fainted after a Molina interrogation. Another one began referring to her as “sir.”

Her acolytes — who called themselves “Molinistas” — began to populate L.A. politics. Mike Hernandez won a seat on the L.A. City Council in 1991. Xavier Becerra finished first in the 1992 race to replace Roybal, the longtime Eastside representative, in a campaign that saw Molina and Torres fight yet another proxy war. The following year, Antonio Villaraigosa — Molina’s representative on the Metro board and the best man at her wedding — went to the Assembly.

“I was like her little brother,” said Villaraigosa, who Molina shunned shortly after his win after she found out he had cheated on his wife but they patched things up in time for his historic 2005 L.A. mayoral victory. “She beat me up like no one else, but I knew it came with the territory. She was tough on all of us, but we all loved her and were loyal to her, and stayed with her.”

Though Molina was an admitted taskmaster, staffers stayed with her for years. She took lunch in the break room with them, and she invited her team to her house every Christmas for gifts and homemade pork tamales.

Speculation about higher positions — mayor, congresswoman, governor, even U.S. senator — swirled as Molina began to assume a national profile. She became close with Bill and Hillary Clinton and served as one of the vice chairs for Democratic National Conventions from 1996 through 2004. But the Board of Supervisors proved Molina’s final stop on her political journey.

Even a Democrat-majority board couldn’t help Molina achieve all of her goals. Repeated bids to increase the number of supervisorial seats went nowhere. Her push for a rebuilt L.A. County-USC facility with 750 beds resulted in only 600. The Gold Line expansion to the Eastside went mostly above ground despite her wishes that it be a subway, and she decried it as “substandard” once it opened. A resolution in 2008 to severely limit street vending failed after a public outcry.

Victories were more common, on issues big and small.

Parks and community centers opened from downtown to the San Gabriel Valley. She set aside tens of millions of dollars in discretionary funds to help create LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, arguing the city needed a museum that told its Latino history. Then there was the time in 2002 when the Board of Supervisors passed an ordinance that forced businesses caught overcharging customers to publicly post notices of their violations. It came after Molina went to Kmart to buy discounted lipstick only to get rung up at the register for the regular price.

“We were trained to always think about [issues] from the context of our parents,” said Miguel Santana, a longtime Molina aide and former chief administrative officer for the City of Los Angeles who’s now the president of the Weingart Foundation. “If it doesn’t make sense to our parents, we need to fix it. And the other mantra was the government should treat our community in the way you want your parents to feel.”

Gloria Molina came to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors in 1991 after a federal court threw out the previous year’s election and ordered a new one for a new district, drawn with boundaries that gave Latinos something closer to a proportionate share of representation.

When she was termed out in 2014, only three other supervisors — Roger Jessup, Kenneth Hahn and Antonovich — had served longer.

“This seat was just a perfect fit,” she told The Times in 2009. “I love what I do and I wish I could stay here forever, but it’s just as well that I move on and find something else, hopefully not elective office.”

That’s exactly what she did just months before she was termed out in 2014, when Molina announced she was going to challenge Eastside Councilmember Jose Huizar the following year.

Followers loved the idea of Molina taking down yet another Eastside politico. She lambasted his focus on developing downtown at the expense of working-class neighborhoods, telling Huizar during a debate, “You’re so busy working with developers and talking about density that you forget about the basic issues.”

Her brawling style no longer drew the adulation of the past. On election night, Molina had about a dozen volunteers working the phones at her campaign office; Huizar had over 60. She pulled in only 24% of the vote, while Huizar easily sailed to a third term.

She never ran for public office again.

Molina spent her retirement easing into her role as the lioness of L.A. politics. She became a regular on panels or in documentaries that retold some of the struggles that she had participated in — the Chicano Moratorium, the L.A. County-USC sterilization scandal, the battle against Proposition 187, even Fernando Valenzuela’s historic 1981 rookie year — for a new generation.

Her lifelong love of quilting led Molina to co-found the East Los Angeles Stitchers, a group of Latinas who held monthly meetings and have vowed to complete the 100-plus quilts Molina couldn’t finish.

She also went on more outings and vacations with a group of friends Molina called “Las Girls,” women who had weathered their own professional battles and found solace among one another for decades.

Monica Lozano, former publisher of her family’s newspaper, La Opinión, first met Molina during the Comisión Mexicana Femenil Nacional days. “You walk into a room with these powerful women talking about issues, and you think, ‘I belong,’” said the former president of the College Futures Foundation. “And that’s what Gloria created even then.”

When Molina became the first Latina on the L.A. County Board of Supervisors in 1991, my mom proudly told me that she was a history maker we should root for, even though we lived in Anaheim.

Las Girls came from across the world to visit Molina near the end of her life. “When we got together, Gloria said, ‘¡Aquí vienen mis comadres!’ [Here come my girlfriends!],” Lozano said. They looked at photos of their lives together. “And Gloria smiled and looked at all of us and said, ‘Look at those powerful Chicanas.’”

Molina is survived by her husband, Ron Martinez; daughter, Valentina Martinez; grandson, Santiago; and siblings Gracie Molina, Irma Molina, Domingo Molina, Bertha Molina Mejia, Mario Molina, Sergio Molina, Danny Molina, Olga Molina Palacios, and Lisa Molina Banuelos. There will be a public celebration of her life at LA Plaza at a forthcoming date.

Even after leaving elected office, Molina insisted that Latino politicians had a special duty to the community that forged them.

“To dismiss it and think, ‘Oh, you know, I’m just here, I’ve just got elected and I can address it, go-along-to-get-along, and I don’t have to be that champion.’ You’re wrong!” she told Cal State Fullerton in 2017. “It’s your job, it’s your duty, it’s your responsibility.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.