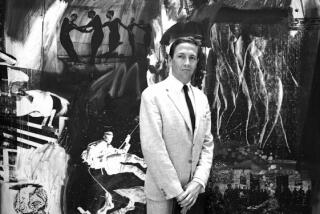

Fred Dewey, former executive director of Venice’s Beyond Baroque, dies

Fred Dewey, the former executive director of Venice’s venerable literary arts center Beyond Baroque, founder of its imprint Beyond Baroque Books, and curator of the Venice Beach Poet’s Monument, has died at a Los Angeles hospital.

Dewey died June 2 from complications of prostate cancer, his brother, John Dewey, said. He was 63.

Dewey, who helmed Beyond Baroque from 1996 to 2010 and secured a long-term lease for it, considered the organization “the nonprofit version” of San Francisco’s famed City Lights Books, he told Publishers Weekly in 2007.

“Fred’s idea was that Beyond Baroque could become a kind of public, active, vibrant countermodel to Hollywood and the art world,” which he considered a “colonization of the imagination,” said artist Jeremiah Day. Dewey believed Beyond Baroque could be the heart of “an active, poetic engagement with our real human condition. And indeed it was.”

Ferlinghetti was the co-founder of the legendary City Lights bookstore and a champion of Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac.

Founded in 1968 as an experimental literary magazine, Beyond Baroque cemented itself as an incubator for writers and seduced scholars, punk rockers and Venice Beat writers into Venice’s original City Hall, the center’s home.

Musician Tom Waits, writer Dennis Cooper, X singer Exene Cervenka, and poets Amy Gerstler and Wanda Coleman were among the alumni of the weekly poetry workshops held Wednesday nights. Gerstler, whose book “Bitter Angel” won the National Book Critics Circle Award in poetry, honed her craft at Beyond Baroque before gaining literary recognition. Amanda Gorman, who captured the world with her poem “The Hill We Climb” during President Biden’s inauguration, took the center’s youth poetry classes as a teenager.

Patti Smith, Michael McClure and Viggo Mortensen, who served on the board, also performed at Beyond Baroque.

Dedicated to expanding public awareness of and participation in the literary arts, the center holds hundreds of readings a year, hosts free writing workshops, exhibits art and offers concerts, film screenings and more.

Dewey took that goal to heart. “He believed in art and poetry and painting,” said artist Lucas Reiner. “He believed that artists and people could really make a difference in the world. Part of his mission was to help empower people.”

During his tenure, Dewey founded the literary press Beyond Baroque Books, which has published nearly 30 books and expanded the organization’s reach in the city. The World Beyond Poetry Festival, launched in 2000 and which ran for several years, was a long-held dream of Dewey’s. For five days, nearly 100 poets read in neighborhoods not their own in an effort to connect with the city’s diverse communities. Beyond Baroque laid the groundwork for it two years prior with a poetic exchange program between Venice and Leimert Park. Latino writers from Self-Help Graphics joined soon after.

“People are more willing to talk ... when they’re sharing something deeply meaningful with each other,” Dewey said at the time. “That’s why poetry becomes the foundation of a new kind of dialogue.”

With support from city politicians Mike Bonin and the late Bill Rosendahl, Dewey curated the Venice Beach Poet’s Monument — four concrete walls along the boardwalk engraved with the words of Jim Morrison, Charles Bukowski, Manazar Gamboa and other well-known poets from the neighborhood.

Several years later, Beyond Baroque’s lease expired, and suddenly it faced an uncertain future. But Dewey secured a 25-year lease from the city for the organization in 2009 for $1 a year. “It was not an easy task,” said Quentin Ring, the nonprofit’s current executive director. “It was a very complicated set of negotiations and there was some political struggle.”

Yet Dewey’s brother felt that running a nonprofit was never his brother’s strength. “He wasn’t a gifted organizational leader but he was a gifted cultural-organization, conceptual, intellectual leader,” he said.

For Allan M. Jalon, a former Times writer, among his favorite of Dewey’s contributions to the center were chairs.

“Beyond Baroque had the worst, most uncomfortable metal chairs,” said Jalon. “I loved the poetry readings but God, I hated sitting in those chairs.”

Many years ago, Dewey found dozens of filthy, thrown-out chairs outside of the Santa Monica Courthouse, which was undergoing renovations. Dewey had a plane to catch that day, so he called a friend to retrieve them.

“It’s posed a crisis for me, getting these chairs,” Dewey told Jalon in 2001. “I think people should sit on hard, uncomfortable chairs when they listen to poems and short stories. This is not the movies. This is art. Movies are there to enable you to sit on over-comfortable chairs, to sink into a morass of sleep. Writing is supposed to wake you up. We live in a time of too many comfortable distractions. Art is about the truth.”

Before his time with Beyond Baroque, Dewey helped establish neighborhood councils for L.A. in the aftermath of the 1992 L.A. uprising. He considered a future in politics, his brother said, but realized it wasn’t for him.

Frederick Rogers Dewey, the eldest of three children, was born July 11, 1957, in New York to great privilege. His father, Gordon Chipman Dewey, was a nuclear physicist and consultant to the Department of Defense after World War II, and his mother, Frances Brook Dear, a Foreign Operations Administration aide. Dewey and his siblings, his brother said, “grew up in a house where you have to be doing good in your life.”

Dewey’s great-grandfathers were John Dewey, the American philosopher and educational reformer, and “JW Dear,” a member of the Confederate Army’s 43rd Virginia Cavalry Battalion, better known as the Mosby’s Raiders.

To their mother’s great dismay, neither Dewey brother joined the military, thus ending a long history of family military veterans.

Dewey graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy, a highly selective, independent high school in New Hampshire, and received a degree in semiotics from Brown University.

In 1985, he moved to L.A. to pursue a career in the film industry. He became a production assistant to director Roger Corman but realized the Hollywood industry wasn’t for him.

After retiring from Beyond Baroque, he split his time between Santa Monica, North Carolina and Germany.

Dewey also served on the graduate faculty of Pasadena’s ArtCenter College of Design and had his writing published in the New Statesman, The Los Angeles Times and elsewhere. He also published “The School of Public Life,” inspired by his profound engagement with the work of Hannah Arendt, the German-American political theorist.

“All the poets and writers in Los Angeles owe him a great, great debt for his work to support the role of poetry in particular and literature in general in people’s lives,” said Ring. “I myself do this and it’s really difficult, challenging work because there’s not a lot of money in it and not a lot of support for writers and artists — but Fred really gave his life to that work.”

He is survived by his sister, Frances Dede Dewey, and brother.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.