Walter Mondale, former vice president and presidential nominee, dies at 93

When Walter Mondale — the pioneering vice president under President Carter — ended up on the losing end of Ronald Reagan’s landmark 49-state landslide in 1984, he fretted that it would dominate, even warp, his legacy.

But in reality Mondale, who as a senator was a spokesman for racial justice and an opponent of the Vietnam War, was a fiery reformer who selected the first female member of a national political ticket; an introspective populist who tried to rally Americans to care for the poor during the Reagan-era ascendancy of industrialists and bankers; and, in retirement, a beloved senior statesman of the Democratic Party and sober-minded prairie practitioner of common sense.

“Many politicians look for personal advantage,” said Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, who counts herself among the many Mondale proteges in his native state, “but he always wanted to do the right thing.”

Known simply as Fritz to both friends and foes, Mondale died Monday at age 93, his family said in a statement. No cause was given.

Despite an election defeat that put him in the same unlucky ranks as Alf Landon, Barry Goldwater and George McGovern — he liked to say that he always wanted to run for president in the worst way — Mondale never became the butt of late-night television or cabaret comedians, though his Scandinavian stoicism sometimes came in for gentle ribbing.

He was respected as much for his dignity in defeat as for his sense of triumph in victory.

“He was the definition of decency in American politics,’’ said Peter D. Hart, who served as Mondale’s pollster in the 1984 presidential race. “Everything that he did was based on appealing to the better angels in our society. He looked out for the underdog, but he also understood what fairness and justice meant. Even the many who opposed him felt that way about him.”

Indeed, when a liberal Minnesota incumbent senator, Paul Wellstone, died in a 2002 plane crash, Democrats naturally turned to Mondale as a stand-in. He did not prevail, but at 74 ran a spirited campaign, a reminder to a new generation of Minnesotans of his quiet, ironic sense of humor and a natural homespun way that lingered with him despite years in a white-shoe Minneapolis law firm and a home in an exclusive suburban enclave.

For all his metropolitan success, Mondale’s voice and vision never ranged far from what he liked to call the “dinky towns’’ where his father served as a Methodist minister in the dark years between the Great Depression and World War II. The foreign trips as vice president and the Tokyo posting in his autumn years didn’t affect him nearly as deeply as the lessons he learned in the southern Minnesota towns of Ceylon and Elmore, hard by the Iowa border.

“The values I learned from my parents stayed with me,” Mondale said in 2013. “It was the idea of service, of doing justice, loving mercy and walking humbly. I heard those words — doing justice, loving mercy, walking humbly with your God — all the time in my youth, and I realized a few years ago that that was what kept me going in my life. It was what I was expected to do.”

In his youth he was known as “Crazy Legs,” a reference to his prowess as a football running back. He worked his way through Macalester College in St. Paul (later finishing at the University of Minnesota) and as a young man he was marked by speeches he heard from two midwestern firebrands, former Vice President Henry A. Wallace of nearby Iowa and Mayor Hubert Humphrey of Minneapolis.

So taken was he with Humphrey (and not with the more radical Wallace, who broke from the Democrats in 1948 and ran for president as the candidate of the Progressive Party) that he approached another figure who would loom large in his life and that of the nation, future Agriculture Secretary Orville Freeman, to work on the Humphrey reelection campaign.

Thus began a fateful connection with Humphrey, who would become a senator and later precede Mondale as vice president and Democratic presidential nominee, and with Freeman, who would win three terms as governor — and with their efforts to keep the Democratic-Farmer-Labor coalition free from the Communists whose activism threatened the liberal but mainstream profile the three sought to nurture.

Mondale would manage Freeman’s gubernatorial campaigns in 1956 and 1958, and Freeman in turn would appoint him, at age 32, as state attorney general. Mondale later would be appointed to the Senate to replace Humphrey, who in 1964 was elected vice president on the Lyndon B. Johnson ticket.

The tie with Humphrey would last with Mondale to his last days.

“He was an enormous influence on me,” Mondale said in the interview for this obituary. “We came from different towns but had the same backgrounds. He helped me shape myself for what I was for. He showed what energy and persuasiveness and a willingness to touch people and stay connected would do. He showed me what you could do with a life.”

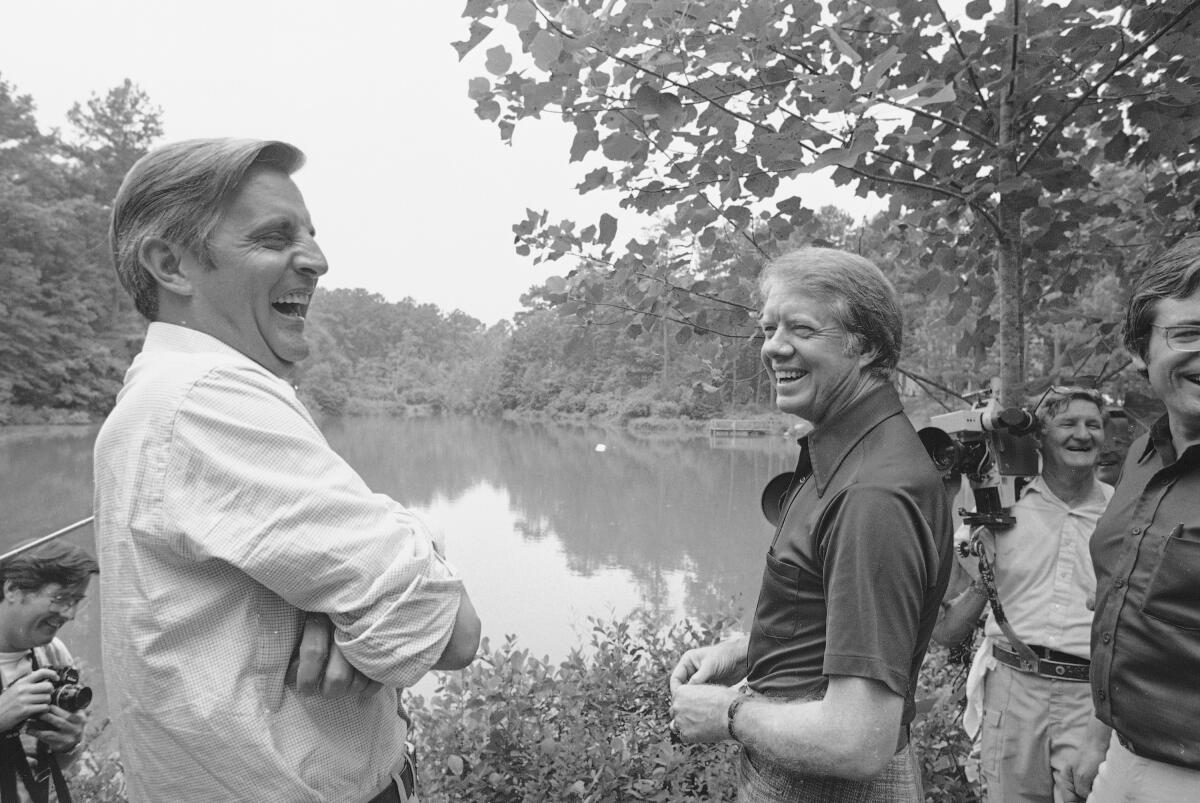

Though Mondale won election as attorney general on his own (later in 1960) and to the Senate (in 1966) he would be labeled by critics as a serial appointee, catapulting into ever higher office by virtue of favors from his mentors. That claim appeared again after he was selected by Jimmy Carter in 1976 to be his vice-presidential running mate.

The Capitol chamber Mondale joined in Washington would be described by author Ira Shapiro as “The Last Great Senate” in a book of that name, and Mondale mingled easily with figures such as Mike Mansfield of Montana, Edmund S. Muskie of Maine, Warren G. Magnuson and Henry ‘’Scoop’’ Jackson of Washington, all Democrats; and with Howard H. Baker Jr. of Tennessee and Jacob K. Javits of New York, both Republicans.

In that milieu, Mondale had a halting, cautious start and then flourished, championing consumer legislation, co-sponsoring the War Powers Act, and opposing two controversial Nixon-era programs, the anti-ballistic missile (ABM) and the supersonic transport (SST).

He was co-chairman of Humphrey’s unsuccessful 1968 presidential campaign and then, eight years later, stood down from a White House campaign of his own, adding two colorful phrases to the American lexicon. He said he did not possess the “fire in the belly” required to run for president, and he said he didn’t want to spend two years in Holiday Inns campaigning for the nomination.

But Mondale eagerly accepted Carter’s invitation to join the 1976 ticket to battle with Gerald R. Ford and his vice-presidential nominee, Sen. Robert J. Dole of Kansas. It was in Mondale’s debate with Dole that the Kansan made his notorious remark about how many Americans had died in what he described as “Democrat wars.”

Mondale was an unusually active vice president, the most active in American history until that point, and unlike so many of his predecessors in the office, including Richard Nixon, Johnson, and Humphrey, he was a full partner with the president, with an office in the West Wing, a weekly meeting with the president, and the ability to walk into the Oval Office when he deemed necessary. This set a precedent that would enable Albert Gore Jr., Dick Cheney and Joseph R. Biden Jr. to play important roles beyond presiding over the Senate, the only vice-presidential role set forth in the Constitution.

“If you want to date the modern vice presidency, you look to the Carter administration,” said Martin Kaplan, who was chief speechwriter to Mondale in the vice presidency and later became the Norman Lear Professor of Entertainment, Media and Society at USC. “Mondale insisted on these changes as conditions for him to go on the ticket, and Carter kept his word.’’

Unusually active, too, was Mondale’s wife, Joan, who was drawn to the visual arts the way her husband was drawn to the political arts.

Before long she was known as “Joan of Arts,” mounting exhibits in the vice presidential mansion on Massachusetts Avenue — the Mondales were the first vice-presidential couple to occupy the house on the site of the Naval Observatory — and traveling the country as an advocate for the arts in public places. Joan Mondale died in February 2014.

With the Carter-Mondale ticket’s defeat at the hands of Ronald Reagan in 1980, Mondale swiftly emerged as the natural Democratic standard-bearer for 1984. He retreated to the turn-of-the-century gray stone home the couple owned in Washington’s Cleveland Park — neighbors included the Washington bureau chief of Newsweek, then an exalted position — and rejoined their old lives of tennis and pottery groups and their membership in the Lowell Street Fruit and Vegetable Cooperative, where Mondale was known as a ``founding eater.

Mondale spent those few wilderness years practicing law but in truth boning up for a presidential run. One afternoon he bounded into an associate’s office to declare that he finally understood the Federal Reserve Bank. He announced his presidential campaign with events in Minneapolis and Hibbing, Minn., an Iron Range town famous as the hometown of Bob Dylan.

From the start, Mondale ran an “inevitability campaign,” seeking to sow the idea that he would be the eventual Democratic nominee and attracting enormous amounts of political-action committee contributions, much of it from labor groups. The commentators thought his principal rival would be Sen. John H. Glenn Jr. of Ohio, the former Friendship Seven astronaut who positioned himself as the candidate of what he called the “sensible center.”

Glenn never took off as a candidate.

The Mondale staff and much of the national press, which all but coronated Mondale, did not foresee the emergence of an insurgent campaign by Sen. Gary W. Hart of Colorado, who artfully portrayed himself as an outsider and pilloried Mondale as the captive of “special interests,” which swiftly became the catchphrase of the year.

While Glenn softened up Mondale by describing him as the candidate of “the bosses and barons” of the Democratic Party, Hart, with the inspired organizational work of Jeanne Shaheen, later governor of New Hampshire and now the senior senator of the state, pulled off one of the great political upsets of the post-war era. The Coloradan won the Granite State primary and gained a shimmery appeal that threatened Mondale, suddenly thrust on the defensive.

“This swiftly became a campaign of one generation versus another and of the future against the past,” Hart said in an interview. “Fritz was a representative of the best of the New Deal, and he ran with the assumption that the tax-paying middle class would continue to pay for all the good things we did in the 1930s and 1960s.”

The Hart-Mondale struggle soon entered a phase of trench warfare, with the outcome uncertain until the last weekend of the primary season. Mondale finally prevailed, with some deft delegate counting the morning after the California primary, which Hart won, and with assistance from the most powerful television ad of the season, a take off of a Wendy’s hamburger ad in which the phrase “Where’s the beef?” was directed at Hart’s “new ideas” campaign.

Weeks later, Mondale stunned the political world by selecting as his running mate Rep. Geraldine A. Ferraro of New York, the first woman on a national political ticket. At the announcement, in the state capitol in St. Paul, Mondale beamed with pride. A Secret Serviceman wept. A generation of girls was inspired.

“This is probably the thing he was proudest of politically,” said Maxine Isaacs, the 1984 campaign press secretary and later a lecturer at Harvard. “He really believed that he changed America forever by doing that. People think he did it as a ‘hail Mary’ because he had nothing to lose, but it wasn’t that. He wanted to use the power of being the nominee to transform the country — and for me it was electric to watch.”

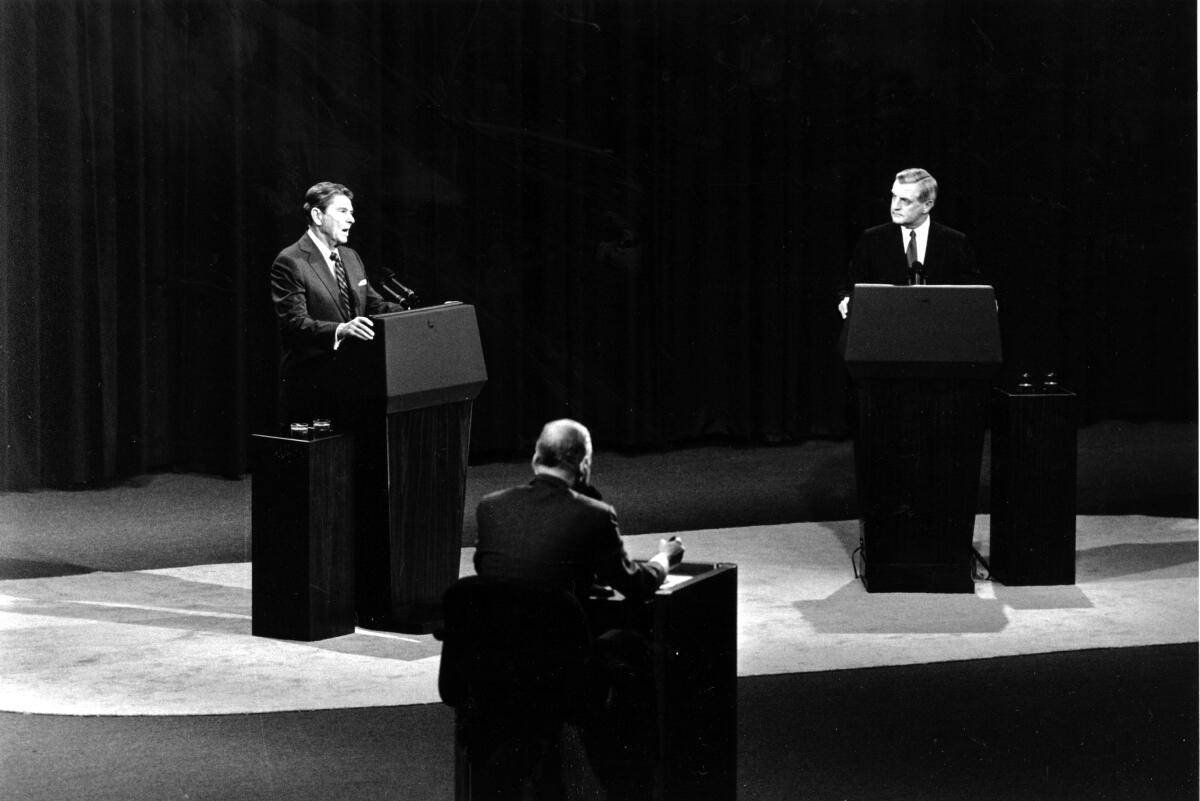

Mondale also attracted attention with his vow to raise taxes — a maneuver at the San Francisco national convention that many analysts believe signaled an early but ineffable death knell of his campaign, which in any case was struggling against a Reagan offensive fueled by a television advertisement that began, “It’s morning again in America.”

The former vice president soundly defeated Reagan in the first televised debate, raising questions about the president’s age and mental competence. But campaign insiders knew by mid autumn that Mondale had little chance. One indication: He was booed by students in Duluth, in his home state. The episode troubled him deeply. “I always had the kids,” he said plaintively in a conversation on his campaign plane after the event. No one who heard that remark from Mondale could ever forget it.

Mondale was gracious in a defeat that was devastating; he lost all but his home state. He began to practice law and, in 1993, was nominated by Bill Clinton to be ambassador to Japan. Once back in the United States, he reported to his Minneapolis law office almost every day until he was well past 90, and when a reporter who had covered his 1984 campaign telephoned him in 2013 and asked him what was new, he said with a laugh, “I’m not doing much.’”

Two years later, in another conversation with that reporter, Mondale thought aloud about that 1984 race. “I’d like to have another go at Reagan,’’ he said, only half joking.

He enjoyed the leisure but remained involved in Democratic politics, cherishing his role as a mentor.

One of his proteges was Thomas E. Donilon, President Obama’s national security adviser. Another was Susan Estrich, the first woman to manage a presidential campaign; she did so for Gov. Michael S. Dukakis in 1988. A third was Ann Stock, who was White House social secretary under Clinton and then assistant secretary of state in the Obama administration.

One of those he mentored was the young Amy Klobuchar, a Yale student from Plymouth, Minn., who learned firsthand of Mondale’s mania for honesty.

As a young woman Klobuchar, who as a Minnesota senator became a 2020 presidential aspirant, won a coveted spot as an intern in the vice president’s office and turned up there, as she remembered, “ready to take on the world.” Not so fast, Mondale seemed to indicate. He gave her an important assignment as her first task in his office. He asked her to climb under each desk and chair and to record the serial number on the bottom. He wanted to be sure that no piece of furniture assigned to his office would go missing.

Mondale was predeceased by his wife and a daughter Eleanor, who died of brain cancer in 2011.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.