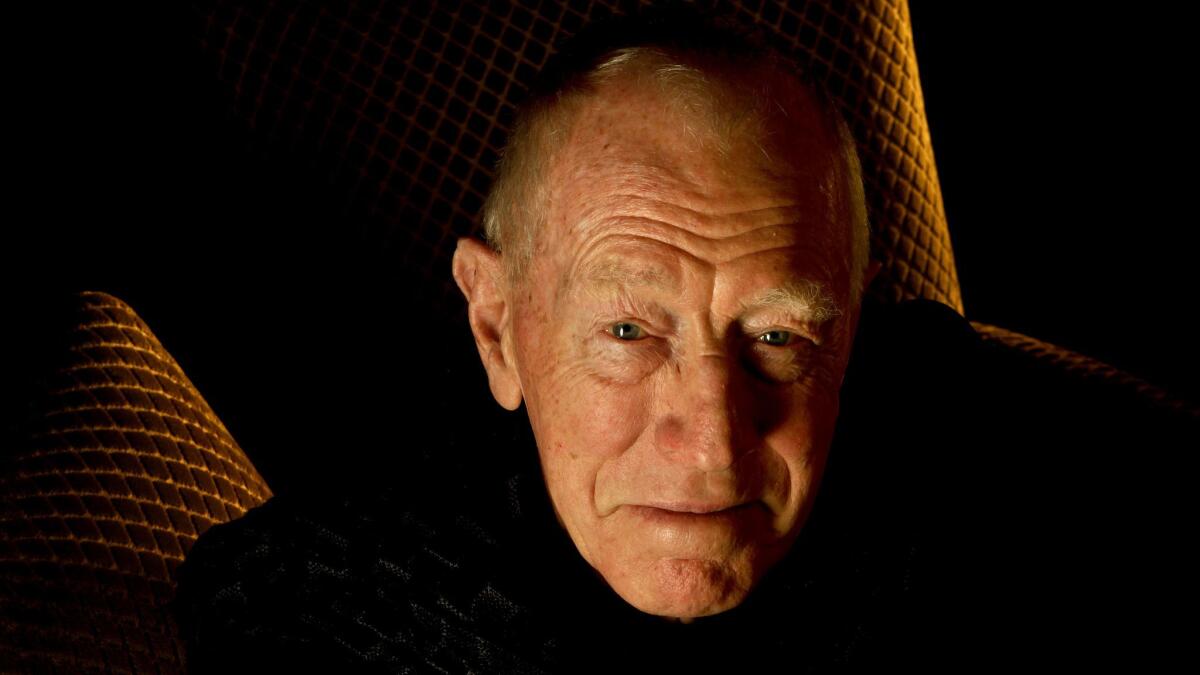

Max von Sydow, Swedish star of Bergman films, ‘The Exorcist,’ dies at 90

For the record:

7:02 p.m. March 17, 2020In a previous version of this story, the first reference to Max Von Sydow’s chess game in Ingmar Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal” stated that he played the game with the devil. As stated in the second reference to the game, he actually played chess with Death.

Swedish actor Max von Sydow, the stately import whose theater roots laid the groundwork for a vast onscreen career in nearly a dozen Ingmar Bergman productions as well as defining roles in “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” “The Exorcist” and “Game of Thrones,” has died.

The two-time Oscar nominee died Sunday, his agency confirmed Monday morning. He was 90.

The veteran actor’s rich repertory included Jesus Christ, clergymen, pontiffs, knights, conquerors, attorneys, sinister doctors, stateside villains and the devil incarnate — and that was just on film. Von Sydow continued to work in theater and smaller Swedish projects in his later years.

In a career that stretches from 1949 onward, there was rarely a year when he didn’t have a project in movie houses.

Many of his films — and there are more than 100 of them — are considered classics, beginning with his early work with Swedish icon and former mentor Bergman. Von Sydow hit the global stage playing chess with Death in Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal” in 1957. It was the first of 11 memorable films with Bergman as part of the filmmaker’s repertory company of actors.

He starred in several of his landmark movies, including 1958’s “The Magician,” 1960’s “The Virgin Spring,” 1961’s “Through a Glass Darkly” and 1963’s “Winter Light.” He played the lead in only six of the 11 features he and Bergman made together between 1957 and 1971. He last worked with the filmmaker on the TV movie “Private Confessions” (1998), written by Bergman and directed by Liv Ullman, a frequent co-star of Von Sydow’s, playing his mother’s Uncle Jacob. He also played his grandfather in 1992’s “The Best Intentions.”

“Whatever good I have done on screen I owe to” Bergman, Von Sydow said in a 2013 Times interview. “I have learned discipline. I have learned concentration and the joy of acting.”

After making his U.S. debut as Jesus Christ in George Stevens’ final film, 1965’s “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” Von Sydow built up an impressively varied body of work that included William Friedkin’s 1973 horror blockbuster “The Exorcist,” Sydney Pollack’s 1975 thriller “Three Days of the Condor” and Martin Scorsese’s 2010 psychological thriller “Shutter Island.”

Von Sydow was only 43 when he played Father Merrin, “The Exorcist’s” titular Jesuit priest, though his devout alter ego was well into his 80s. Makeup artist Dick Miller added years to his visage and the actor earned his second Golden Globe nomination for the role (his first was for 1966’s “Hawaii” with Julie Andrews and Richard Harris) and the horror classic was among his biggest box-office successes.

His portrayal of an impoverished farm worker in 1988’s “Pelle the Conqueror” by Danish filmmaker Bille August, is often considered one of his greatest roles and it brought him worldwide acclaim as well as his first lead actor Oscar nomination, despite it being a foreign language film. The film was Denmark’s official Oscar entry and won in the foreign language category. That role went against the grain of Von Sydow’s usual authority figures, casting him as the weathered Swedish widower Lasse whose remarkably tender father-son relationship is at the heart of the film.

Von Sydow also made his fair share of popcorn vehicles too — out of “curiosity” and a need for “change.” The art house regular was generally cast as the international villain, appearing in campy fare such as “Flash Gordon” or David Lynch’s “Dune” or “Judge Dredd” with Sylvester Stallone. He played the sodden King Osric in “Conan the Barbarian,” the dapper assassin in the fedora in “Three Days of the Condor,” and the shifty-eyed bureaucrat of “Minority Report.” Von Sydow’s late-in-life roles capitalized on his advanced age and he appeared in high-profile genre parts such as a career art forger in “The Simpsons,” the clairvoyant Three-Eyed Raven in HBO’s “Game of Thrones” and spiritual elder Lor San Tekka in “Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens.” His fantasy work in “Thrones” clinched him a second Primetime Emmy Award nomination in 2016. (He earned his first nod for 1989’s “Red King, White Night.”)

“My problem is that too often casting directors or producers ask me to do roles I’ve done before, and that is boring,” he told The Times in 2012. “I can’t imagine how many priests and saints and popes I’ve played; not only that, Jewish refugees and Nazi officers, etc. And now at my age, what parts are there in the scripts? They’re all grandfather roles. Old roles. They die, usually.”

And such was the case in his 2012 turn in “Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close,” which he was attracted to because it was a fresh role and earned him his second Oscar nomination. The octogenarian actor had no spoken lines in the post-9/11 drama but was unforgettable nonetheless, delivering a warm, quirky performance as his Renter character communicated through writing.

At 6-foot-4, Von Sydow was a commanding presence wherever he appeared and paid meticulous attention to tiny details in his work, explaining why many film experts consider the veteran Swedish actor to be one of the giants of international cinema. His peers often remarked on his mastery and how decent, generous and courteous he seemed. Director Jan Troell said that he witnessed Von Sydow losing his temper only once and then “for only 27 seconds,” after a day of shooting in a snowstorm for his 1971 historical drama “The Emigrants.”

“He has such tremendous technique, but it’s all invisible,” noted director Scott Hicks, who worked with Von Sydow on “Shine” and “Snow Falling on Cedars” in the 1990s.

Retirement was usually a fleeting idea that Von Sydow quickly dismissed: “As long as you are in command of your physical and mental abilities, why not continue? My wife has promised to tell me when to stop.”

Born in 1929 as Carl Adolf von Sydow in Lund, Skåne, Sweden, Von Sydow grew up in an aristocratic middle-class family as the son of Baroness Maria Margareta, who was a teacher, and Carl Wilhelm von Sydow, an ethnologist and folklore professor at the University of Lund.

There was no theater in his hometown and his parents were not much for going out. Von Sydow remembers being taken to the pictures by his father only twice, according to a 1988 Times story. Seeing a production of “Midsummer Night’s Dream” in the next town was life-changing and prompted him to start a drama group at his high school. After completing compulsory military service he applied to the Royal Academy in Stockholm and was accepted.

He made his debut in a small part as the Prince of Orange in Goethe’s “Egmont,” and it was “almost a disaster,” he told The Times. “I had to come on stage and give a terrible tongue-lashing to an older actor. Unfortunately, he was one of my idols, a man I worshiped. And I had a hellish time making myself do it.” But he did, and although the whole production indeed proved to be a disaster, Von Sydow got good reviews as a promising newcomer.

Years in provincial theater followed. The work trained him early on to appreciate the variety of roles: “Big parts, small parts, classical, modern, comedy, tragedy, anything. Always something new, which was a wonderful school for a young actor. I was, in a way, very spoiled.”

At the last of three repertory companies, the director was Bergman and Von Sydow made two films before Bergman cast him in “The Seventh Seal,” giving a mesmerizing performance as a 14th century knight who challenges Death to a game of chess, which catapulted the tall, imposing Swedish actor onto the international scene.

“Little did we know how important that film would be,” he said. “We knew it was important, because it was so different from everything else that was being done. But we had no idea it would find such audiences abroad. Now so many people tell me it was the first foreign film they ever saw.”

Of Bergman, who died in 2007, Von Sydow said the filmmaker was “courageous in choosing people to do things that they themselves might not expect to play. Life was exciting.”

Von Sydow first traveled to Hollywood to meet with “The Greatest Story Ever Told” director Stevens to play Jesus Christ in the biblical epic.

“I didn’t want to do it for various reasons, but he was after me, and my agent tried to convince me I should. George Stevens said, ‘Why don’t you come over and see what we are doing and we will show you that we are doing something important,’” he told The Times in 2013. “I was seduced, of course, by Hollywood and Mr. Stevens. He was a remarkable man. I admired him very much, but he was not easy. He probably postponed decisions as long as he could. Watching the film now, I must say I am disappointed he didn’t get closer to the characters. There are very few close-ups. It’s aesthetically a very beautiful film, but I think it’s a little cold. But he was a remarkable filmmaker.”

It was Von Sydow’s first English-language production. Decades later, he would play the devil in the 1993 film “Needful Things.” He took on a number of roles, leading and otherwise, in a variety of genres, always lending a levity to the work — whether playing Ming the Terrible in “Flash Gordon” or appearing in “Rush Hour 3” or a video game such as “The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim.”

“I don’t have a philosophy for choosing roles,” he told The Times. “Sometimes, it’s just, ‘This might be interesting, that might be fun to do.’ There might be interesting actors or directors in the project, even if the part is not important. And then sometimes, you need the money.”

In 1951, he married actress Christina Inga Britta Olin and together they had two sons, Clas and Henrik, who appeared with him in “Hawaii.” He and Olin divorced in 1979. Von Sydow later moved to Paris with his second wife, documentarian Catherine Brelet, whom he wed in 1997. He surrendered his Swedish citizenship to become a French national in 2002 and adopted her two children from a previous marriage. Although some Swedish-language projects continued to pepper his resume, he missed his home country, specifically the ability to express himself accurately.

“I could never learn to be totally fluent in any other language,” he said, “which means that the Swedish language is my best tool. I have desperately tried to get English and French, but I’m never happy with the results. I just feel I’m not free.”

He told The Times that he would like to be remembered “as a competent actor.”

“What will probably stick are the films, unfortunately; people who have been to the [live] theater have memories of things that are not visible, and only in the memories of the audience. I just hope they remember something I’ve done — whatever it is — that something I’ve done has meant something.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.