Robert Evans, producer of ‘Chinatown’ who saved Paramount Pictures, dies at 89

As the chief of Paramount Pictures, Robert Evans presided over a remarkable run of film classics including “Chinatown” and “The Godfather.” And his flamboyantly over-the-top lifestyle was nearly as cinematic as any of them.

He had a natural eye for powerful hit movies, an ability so fine-tuned he was credited with saving Paramount. But away from the studio his life was so calamitous and excessive that he nearly lost it all and was ultimately ousted from his perch atop the studio.

Described by former Times film columnist Patrick Goldstein as “one of the great self-invented characters of our age,” Evans reached meteoric heights during his reign as production chief of Paramount in the late 1960s and early `’70s, presiding over blockbuster hits that revived the ailing studio’s fortunes. Along the way, he transformed from a sportswear mogul into a noted independent producer.

But he fell from grace in the 1980s when he was involved in a drug scandal and later linked to a high-profile murder case — unexpected true-life plot twists that, as Evans put it, turned him from “legend to leper.”

Evans, who died in Los Angeles on Saturday at age 89, has been characterized as vain and self-destructive, warm and loyal, a romantic rather than a businessman, a legendary ladies’ man, a glamorous gambler, the last of a dying breed and a survivor.

“If Evans were a racehorse,” “Chinatown” screenwriter Robert Towne once said, “they’d have to call him Caution to the Winds.”

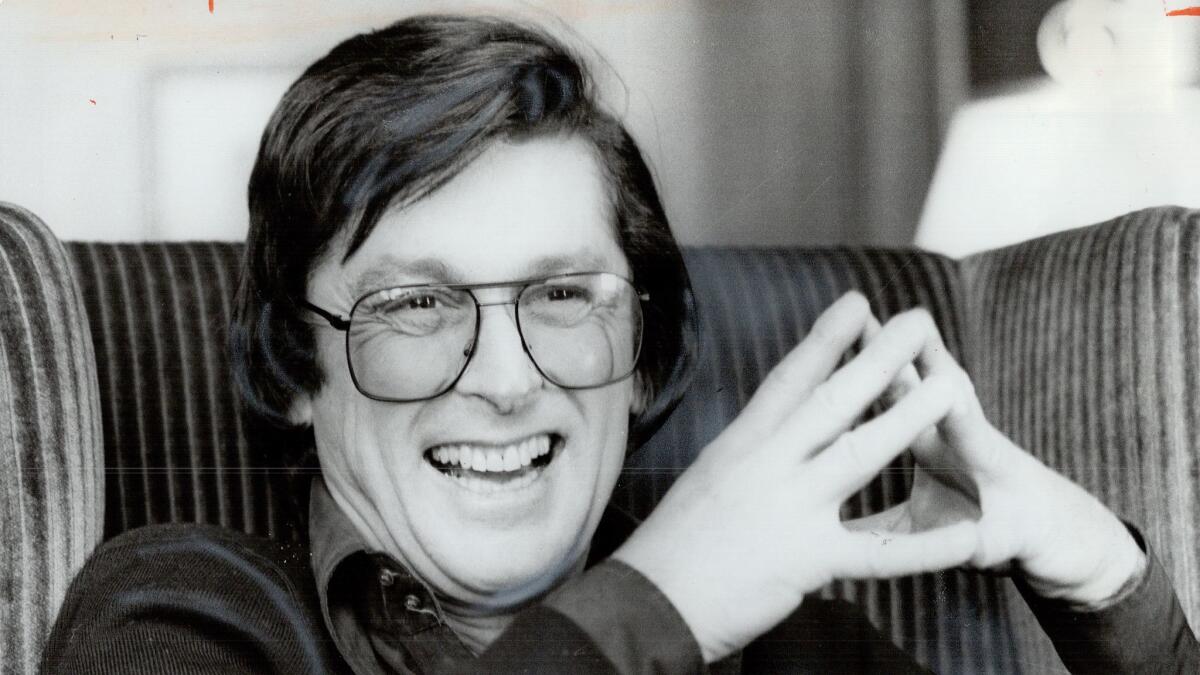

Producer Robert Evans, whose death was revealed Monday, was remembered for his achievements but also his notorious lifestyle.

Evans’ flamboyant life and style (the perpetually tanned skin, the oversized glasses, the turtlenecks) became fodder for parody — Dustin Hoffman played a big-glasses-wearing, tanning-bed-using, Evans-like movie producer in the 1997 dark comedy “Wag the Dog” — and self-parody: Evans voiced his own title character in “Kid Notorious,” a 2003 Comedy Central cartoon series that was inspired by his storied life in Hollywood.

He was a master of self-promotion and reinvention, resurfacing in the 1990s after a decade of professional and legal troubles with a candid bestselling autobiography, “The Kid Stays in the Picture,” and a revived career as an independent producer, albeit with far less success than during his heyday.

Evans was a Hollywood first: a onetime actor who became the production head of a major movie studio.

“He wasn’t a star as an actor, but he was a star as a producer-studio head,” veteran producer Lawrence Turman, chair of the Peter Stark Producing Program at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, told The Times in 2008.

One of three children, he was born Robert J. Shapera on June 29, 1930, in New York City.

A former teenage radio actor in New York City in the 1940s whose late-’50s fling in the movies included playing Ava Gardner’s bullfighter love-interest in “The Sun Also Rises,” Evans also was a partner in the pants division of Evan-Picone, the successful New York women’s sportswear company co-founded by his brother Charles in 1949.

The company, Evans said, made him a millionaire before he was 25. But his heart was in show business, and a couple of years after the company was sold to Revlon, he reinvented himself as an independent Hollywood movie producer.

But before he had amassed even a single screen credit as a producer, the 36-year-old Evans was handpicked in 1966 to head production at Paramount Pictures. The appointment of a former women’s clothing manufacturer and a one-time actor with no track record as either a producer or a studio executive was greeted with ridicule by many in Hollywood.

As he went about overseeing an expanded production schedule and attempting to make “Paramount paramount in the film industry again,” Evans began generating as much “ink” as the latest Hollywood starlet.

“The playboy peacock of Paramount,” Life magazine called him in a lengthy 1969 story that included a two-page Alfred Eisenstaedt photo of the young mogul at home in bed conducting business on the phone and surrounded by scripts and a breakfast tray.

Home was a 16-room, art-filled French Regency mansion in Beverly Hills — a nearly 2-acre tree- and rosebush-filled estate with an egg-shaped swimming pool, a tennis court and a movie theater, where a black-tied butler served guests brandy before a picture was screened.

“He is entirely too good-looking, too rich, too young, lucky and too damned charming,” said the magazine. “Who the hell does he think he is? If there’s anything Hollywood wants out of Robert Evans, it’s to see him fail.”

Evans struck out with films such as “Paint Your Wagon,” “Darling Lili,” “Catch-22” and “Tropic of Cancer.”

But over time, he oversaw a growing number of memorable movies produced and/or distributed by Paramount that included “Rosemary’s Baby,” “The Odd Couple,” “Goodbye, Columbus,” “Romeo and Juliet,” “True Grit,” “Harold and Maude,” “Play It Again, Sam” and “Paper Moon.”

By the end of 1971, Paramount had gone from last place to No. 1 among the major studios.

In a statement to The Times on Monday, the studio described him as “one of its most influential and iconic figures.”

“He was a valued and beloved partner to Paramount Pictures for over half a century, and his contributions to our organization and the entertainment industry are innumerable and far-reaching. As an actor, a producer and a leader, he has left an indelible mark on our studio and the world of film. His influence will be felt for generations to come.”

Evans credited “Love Story,” starring Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal, with saving Paramount from bankruptcy: The 1970 romantic tear-jerker became the year’s No. 1 box-office hit.

MacGraw, New Hollywood’s “It Girl,” had become Evans’ third wife in 1969. The marriage produced Evans’ only child, Joshua, and ended in just a few years.

Evans blamed himself for the breakup of their marriage, saying he had neglected his wife and had not visited her on location in Texas so that he could focus on what became the studio’s landmark masterpiece: “The Godfather.”

He later said he had optioned author Mario Puzo’s work-in-progress — a fictional tale of an Italian American organized-crime family — for $12,500. Three years after the 1969 publication of Puzo’s international bestselling novel, director Francis Ford Coppola’s film version of “The Godfather” became the No. 1 box office hit of 1972 and went on to win three Academy Awards, including the Oscar for best picture.

For Evans and Coppola, “The Godfather” was marked by intense creative battles and Coppola’s anger over Evans’ claims of playing a crucial role in the final edit of the film — so much anger that Coppola stipulated that Evans not have anything to do with “The Godfather: Part II,” which won the best picture Oscar for 1974.

In death, however, Coppola was much kinder to his one-time rival.

“I remember Bob Evans‘ charm, good looks, enthusiasm, style and sense of humor,” the Oscar winner said in a statement to The Times. “He had strong instincts, as evidenced by the long list of great films in his career. When I worked with Bob, some of his helpful ideas included suggesting John Marley as Woltz and Sterling Hayden as the Police Captain, and his ultimate realization that ‘The Godfather’ could be 2 hours and 45 minutes in length. ... May the kid always stay in the picture.”

While still head of production at Paramount, Evans was given a five-year deal to make one picture a year under his own production banner at the studio.

His first was “Chinatown,” director Roman Polanski’s 1974 detective mystery set in 1937 Los Angeles; it starred Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway and won an Oscar for screenwriter Robert Towne. A film involving corruption, murder and incest, “Chinatown” is considered one of the greatest films ever made.

The 1980s, however, marked a dramatic slide in Evans’ professional and personal fortunes, one coming on the heels of a cocaine habit he developed in the mid-’70s.

In 1980, he was implicated in the New York undercover cocaine-buying bust of his brother Charles and brother-in-law Michael Shure. In the end, all three pleaded guilty to misdemeanor drug charges.

Evans could have spent a year in jail, but a federal judge gave him a year’s probation and offered to expunge the charges and dismiss the case if he used his “extraordinary creative talents” in a national anti-drug education program.

The ensuing Evans-produced weeklong series of anti-drug messages, “Get High on Yourself,” featured scores of movie, TV and sports celebrities and was kicked off with an hourlong NBC special in 1981.

The high-profile drug case, he later wrote in his book, turned his life “from one of pride to one of disgrace.”

But things only grew worse when his name was linked to the 1983 murder of Roy Radin, a 33-year-old theatrical promoter from New York, who had entered into an agreement with Evans to finance a motion picture company at a time when Evans was seeking funding for his next film, “The Cotton Club.”

Evans had been introduced to Radin by Karen DeLayne Greenberger, a woman Evans admitted to having an affair with and whom authorities later described as a major West Coast cocaine trafficker.

Radin’s bullet-riddled body was found in a dry wash near Gorman, Calif., a month after he disappeared in 1983.

Five years later, Greenberger and three men were arrested in connection with what was dubbed the “Cotton Club” murder.

A witness at the 1989 preliminary hearing testified that one of the defendants in the case had told him that Evans and Greenberger were responsible for ordering Radin’s murder. But Evans was never charged and Greenberger testified that Evans had nothing to do with Radin’s death. In 1991, she and the three men were found guilty of the murder.

Evans’ reputation, however, was in tatters.

To make matters worse, “The Cotton Club,” the over-budget, Coppola-directed film that Evans had hoped would restore him to prominence, flopped at the box office in 1984.

“Doors closed on me quietly,” he later wrote of this period. “Calls made were not returned.” In time, he was told he had to vacate his longtime office at Paramount.

In a “subliminally masochistic” move, Evans sold his beloved estate, Woodland, to a neighbor on the condition that he be allowed to continue living there as a renter. Without telling Evans, his pal Nicholson flew to Monte Carlo and successfully pleaded to the owner to sell the house back to Evans.

Buying back Woodland symbolized a new beginning for Evans.

In 1991, he launched his professional comeback when he was reinstated as a producer on the Paramount lot. He spent the remainder of the decade producing the films “Sliver,” “Jade,” “The Phantom,” “The Saint” and “The Out-of-Towners.”

As Evans, then 67, told The Times in 1998: “A guy my age doesn’t get a second chance. But I did.”

Years later, the aging Hollywood icon continued to get mileage out of his colorful life story.

He narrated the 2002 documentary adaptation of “The Kid Stays in the Picture.” And in providing the voice for the animated “Kid Notorious” a year later, he scored another Hollywood first.

As Evans liked to say: “I stand alone in the history of Hollywood as someone who started his career as the head of a studio and ends up as an animated cartoon.”

Evans, whose memoir “The Fat Lady Sang” was published in 2013, suffered a series of strokes late in life and was forced to walk with a cane.

Evans was married seven times — to Sharon Hugueny, Camilla Sparv, Ali MacGraw, Phyllis George, Catherine Oxenberg, Leslie Ann Woodward and Lady Victoria White. With the exception of his brief marriage to Oxenberg, which was annulled, all of his marriages ended in divorce. He is survived by his son.

Staff writer Nardine Saad contributed to this story.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.