Paul Crouch dies at 79; founded Trinity Broadcasting Network

In the mid-1970s a vision came to Paul Crouch, but it wasn’t what a man of the cloth might have expected.

A map of North America had appeared on his ceiling, glowing with pencil-thin beams of light that shot in every direction. “Lord,” asked Crouch, a Pentecostal minister, “what does this mean?”

God, according to Crouch, had just one word for him: “Satellite.”

Crouch, who belonged to the Assemblies of God, had been trying to spread the Gospel through a small television station in Tustin, but the vision changed his business plan. He bought more television stations, then piled on cable channels and eventually satellites, filling the airwaves with evangelical programming until he had built the world’s largest Christian television system — the Trinity Broadcasting Network, or TBN.

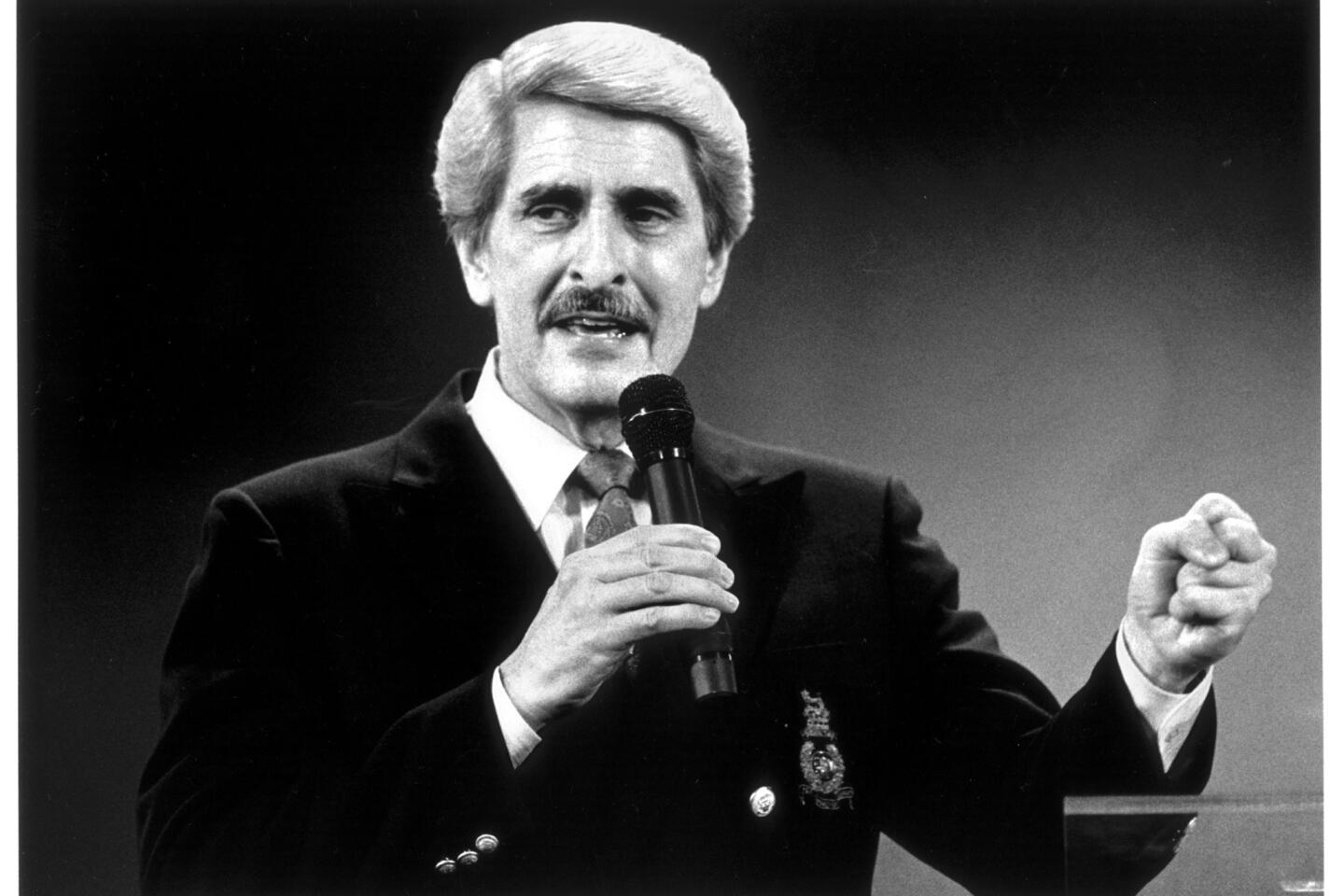

The controversial pioneer of televangelism, whose broadcast empire was called “one of evangelicalism’s most successful and far-reaching media enterprises” by the Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism, died Saturday, said his grandson, Brandon Crouch. He was 79.

Crouch, who had heart problems and other ailments, was hospitalized in October when he became ill during a visit to a TBN station in Colleyville, Texas. In early November the network announced that he had improved enough to return to California. His family did not immediately disclose where he died or the cause of death.

TBN was not the first Christian network — televangelist Pat Robertson had launched the Christian Broadcast Network a decade earlier — but TBN surpassed its rivals in scope and ambition, bringing the word of God to a global audience of millions.

“He has created an enormous platform for many ministries to do what he says is very important to him — that is, to spread the Gospel not only in this country but around the world,” said Steve Strang, founder and chief executive of Charisma Media, a leading publisher of books and magazines for charismatic and Pentecostal Christians.

The son of a poor missionary, Crouch was known for preaching a gospel of prosperity. His twice-yearly Praise-a-Thons on TBN generated as much as $90 million a year in donations, mostly in small amounts from lower-income Americans. “When you give to God,” Crouch said in a typical appeal, “you’re simply loaning to the Lord and he gives it right on back.”

Crouch channeled much of the revenue into charity, funding soup kitchens, homeless shelters and an international humanitarian organization, Smile of a Child, founded by his wife, Jan. In 2011 he donated more than 150 low-power TV stations to Minority Media and Telecommunications Council, which helps minorities, women and other underrepresented communities own and operate TV and radio stations.

But Crouch’s main mission was to build an alternative to secular media, a dream he achieved with single-minded devotion and creativity. TBN, which celebrated its 40th anniversary this year, is a 24-hour family of networks with something for nearly every evangelical Christian demographic. Offerings have included Biblical cartoons and soap operas, game shows, programs on fitness and faith healing, religious movies and late-night Christian rock videos. Prominent independent ministers such as Robertson, Jimmy Swaggart and Robert Schuller bought airtime on TBN, which also broadcast Billy Graham’s crusades.

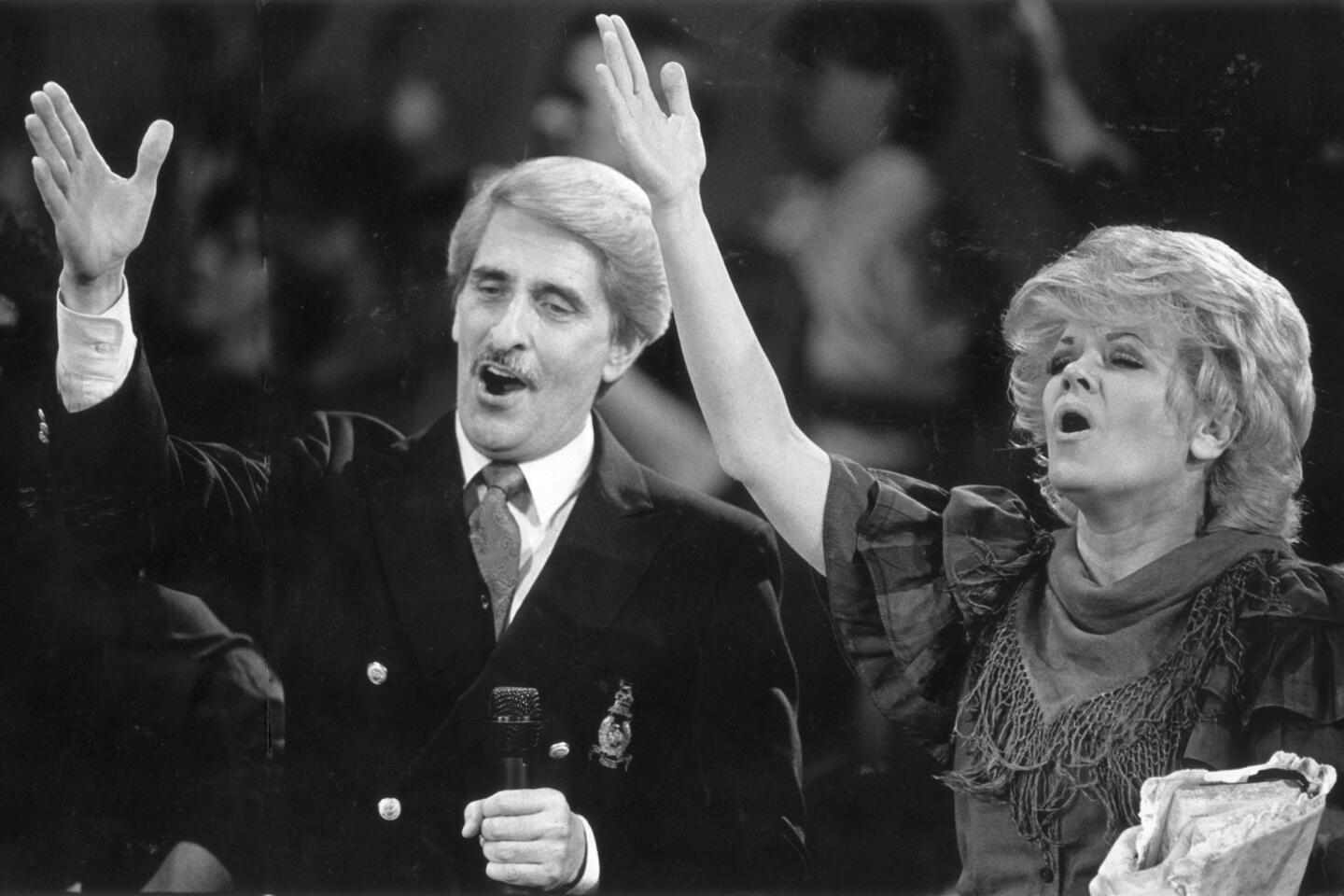

The center of Trinity’s lineup has long been the nightly talk show “Praise the Lord.” Hosted by the silver-haired Crouch and his flamboyantly coiffed wife, it emanates from an Orange County studio decorated with stained-glass windows, gilded imitation antiques and plush pews for the audience.

The extravagance carried over to Crouch’s personal life, provoking criticism from watchdog groups as well as members of his family. He and his wife had access to TBN’s multimillion-dollar private jets and more than two dozen ministry-owned homes, including his-and-her mansions in Newport Beach, a mountain retreat near Lake Arrowhead and a ranch in Texas.

In 2012, granddaughter Brittany Koper, who had been the network’s finance director, went public with detailed allegations of fiscal improprieties, including excessive salaries, four-figure expense-account meals and a $100,000 mobile home for Jan Crouch’s dogs paid with tax-exempt donations.

Koper’s accusations were widely covered by the mainstream press, as was a charge by her sister, Carra Crouch, who said she was raped by a TBN employee and forced by her family to cover up the crime.

Amid the flurry of negative headlines, their father, Paul Jr., quit TBN, where he had held staff and board positions, leaving his younger brother, Matthew, as heir apparent.

The family disputes were the latest in a series of embarrassing events over recent years, including news reports in 2004 that Crouch had paid a former employee $425,000 to keep quiet about claims of a homosexual tryst. Crouch denied having sexual contact with the employee.

Crouch “has a mixed legacy,” said Kurt Fredrickson, associate dean of the doctor of ministry program at Fuller Theological Seminary, the evangelical graduate school in Pasadena.

“He has had a wonderful and profound influence on people’s lives individually. His pioneering work with a new technology has been extremely influential. But that gets tarnished by some of the negative issues that damaged his reputation and hurt what I would call the cause of Christ,” Fredrickson said. “I know too many people who turn on TBN because it’s as good as ‘Saturday Night Live’ sometimes. They say, ‘Wow, this is just so outlandish’ or ‘I wish I had a gold throne.’ They’re intrigued by the side-showness of it.”

At the same time, the television ministry molded the spiritual habits of masses of people, leading to “the conversion, healing, and baptism of thousands who have reported their experiences in letters to the Crouches,” J. Gordon Melton and Jon R. Stone wrote in “Prime-Time Religion: An Encyclopedia of Religious Broadcasting.”

Said Pastor Jack Hayford, whose services at the Church on the Way in Van Nuys were broadcast on TBN for more than 30 years: “It is no exaggeration of terms to describe Dr. Paul Crouch’s contribution to global Christianity as incalculably broad.”

Paul Franklin Crouch was born March 30, 1934, in St. Joseph, Mo. He spent part of his early childhood in Egypt, where his father, Andrew, was an Assemblies of God missionary. When Paul was 7, his father died, leaving his mother, Sarah, to support the family on her meager earnings as a seamstress.

“The difference between, you know, turning lights off and on in the house was the difference between whether we had adequate food to eat sometimes,” Crouch told The Times in 1989.

When he was 15, the husband of the woman who gave him free piano lessons taught him to use a ham radio. A few years later, as a student at Central Bible College and Seminary in Springfield, Mo., Crouch formed a ham radio club and built a small campus radio station. He said it soon dawned on him that “this electronic tool called radio and later television would really be the way to get the Gospel that we preach out in a mass way.”

After graduating in 1955, he married Janice Bethany, the daughter of a prominent Assemblies of God minister. They moved to Rapid City, S.D., where he became associate pastor of a tiny church. The job paid so little that he moonlighted as a deejay at a local radio station.

In 1962 he and Jan moved to Burbank for a job managing the Assemblies of God’s new motion picture and television division. In 1973, he struck out on his own, investing $20,000 from his savings in a struggling UHF station in Tustin that became KTBN Channel 40.

About two years later he was sitting in his den when his life changed. “It was as though the ceiling of my den completely turned into a giant TV screen,” he told The Times in 1989, “and I saw the outline of the entire North American continent as though I were out in outer space.” When he heard the word satellite, “I knew I had heard the voice of God,” he recalled, “and I absolutely obeyed it.”

The first years were difficult. The Crouches ran religious programming for a few hours every night, broadcasting from a spartan set consisting of a folding chair and a shower curtain from Sears as a backdrop. After two nights on the air, they were broke. So the following night they staged a telethon. As an incentive, they announced that an anonymous donor had promised $20,000 if viewers matched the amount. The Crouches raised $30,000 in pledges without revealing that they were the anonymous benefactor.

“Without really realizing it at the time, I had put into motion one of God’s most powerful laws — the law of giving and receiving, sowing and reaping,” Crouch later wrote.

One of Crouch’s early partners was Jim Bakker, a charismatic preacher he had worked with in Michigan. Bakker went on to form the rival PTL Network with wife Tammy but lost his TV pulpit in a scandal involving sex and money.

Crouch continued on his path to building the country’s most-watched religious network, but the road had bumps.

In 1989, in the wake of the Bakker scandal, the National Religious Broadcasters, a voluntary association, investigated complaints that TBN had violated ethical standards. One of the complaints came from Marvin L. Martin, a former producer of “Praise the Lord,” who said he had been fired after questioning the Crouches’ financial practices and moral fitness. He specifically complained that at a TBN staff prayer meeting Crouch asked God to kill a man who had petitioned the Federal Communications Commission to take over the network’s flagship station in Orange County.

Crouch responded that he “probably did pray that God would kill anyone or anything that was attempting to destroy the ministry.” He offered no apology and said his prayer “has not changed.”

The NRB dropped the investigation for lack of evidence.

In 1991, the FCC began to examine accusations that a minority-controlled company TBN had created to buy a Miami commercial station was a “sham front” that allowed the network to own more commercial stations than the 12 allowed by law. After a protracted legal battle, an appeals court ruled that the federal ownership rules were unclear and that the network could not be punished.

“I would rather be charged by men for trying to secure too many stations, than to be charged by God for trying to secure too few,” Crouch said before the FCC was forced to drop its challenge.

Crouch’s empire eventually included several networks, including one with Spanish-language programs, a Christian entertainment center outside Nashville, a Biblical theme park in Orlando, and a gleaming headquarters in Costa Mesa called Trinity Christian City International, which includes among its attractions a simulation of the ancient route along which Jesus was said to have dragged his cross to Calvary. Crouch recently opened a state-of-the-art studio in Jerusalem.

His survivors include his wife, sons and grandchildren.

Times staff writer David Zahniser contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.