Surveillance cameras and the Boston Marathon bombing

Investigators in the Boston Marathon bombing closed in on suspects with surprising alacrity, shifting from “few leads” to “possible arrests” in a matter of hours. That’s due in part to the ample resources and expertise that city, state and federal authorities threw at the crime scene. But it also reflects how much investigators had to work with. We should celebrate the former but think carefully about the latter.

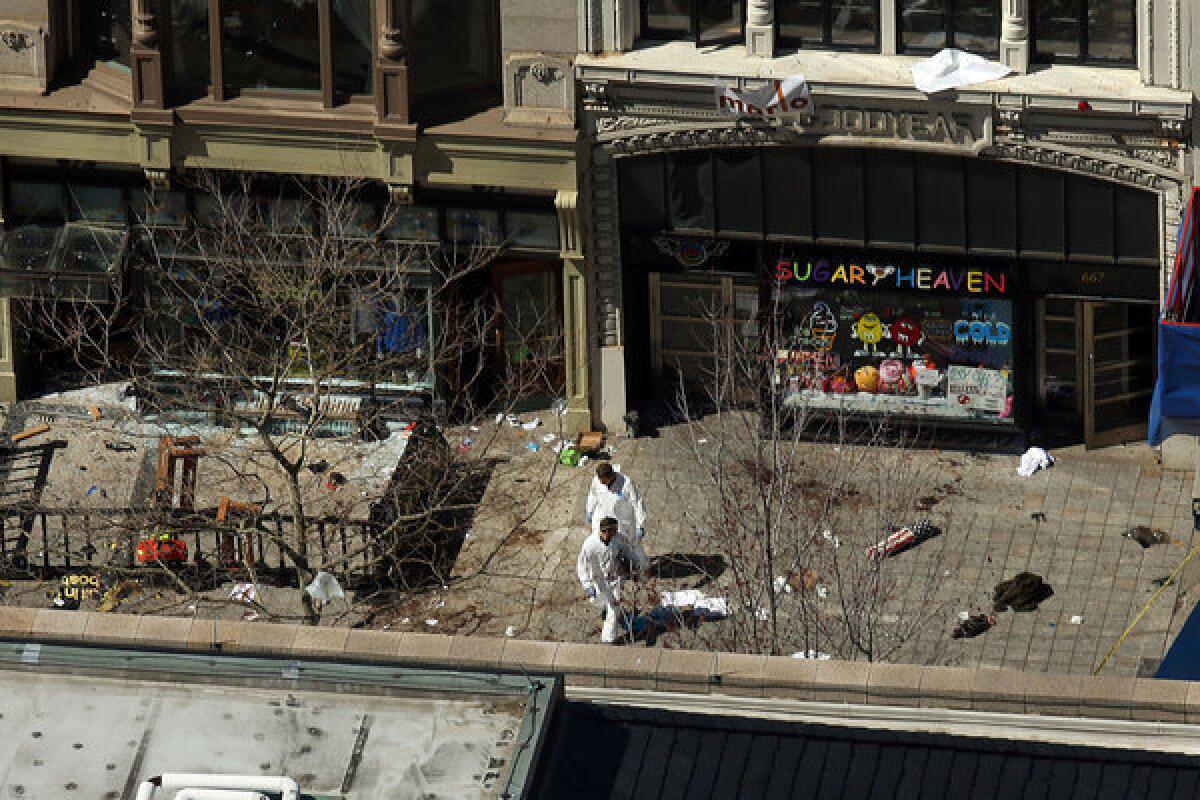

The marathon evidently made for an inviting target because it’s a famous event that draws a huge crowd into a relatively confined space, to wit, the finish line. The same factors, though, can be helpful to investigators. In the hours leading up to the detonations, the attack site was being photographed and videoed continuously by people who’d come to cheer on relatives and friends in the race. Those blocks had to have been among the most closely watched and recorded places on Earth, albeit in a disjointed way.

Police urged the public to send in what they’d recorded that day with their smartphones and cameras. According to some early reports, investigators may have been led to one or more suspects Wednesday by surveillance video from a department store on Boylston Street, Lord & Taylor. Apparently the company had cameras that pointed onto the street, cataloging the comings and goings near its entrance.

FULL COVERAGE: Boston Marathon attack

This sort of private surveillance of public areas is increasingly common. Many retailers, hotels and apartment buildings have cameras at the entrances that are constantly recording the view out front. Banks have street-facing video cameras at their outdoor ATMs. And mobile-phone networks note the movement of phones on their networks, along with the calls placed, messages sent and received, online services used and websites visited.

“It’s true that a great deal of our lives, particularly in public, are recorded today. But for the time being, it’s fairly atomized,” said Ryan Calo, an assistant law professor and privacy specialist at the University of Washington. Unlike a government-controlled surveillance system, Calo said, much of the information-gathering in the United States is being done by private companies for specific, private purposes, such as warding off shoplifters. “Then the question becomes, what does it take to access these atomized sources of recordings?”

It’s fine when government investigators pour through the data in response to an attack like the one in Boston, Calo said. What’s troubling, he added, is when the government uses such routinely collected data to try to identify suspects pre-emptively, before there’s any evidence that a crime is being planned.

The Founders weren’t willing to give the government that much discretion, Calo said. The 4th Amendment was specifically designed to bar “general warrants” that enabled the police to go on fishing expeditions, requiring them instead of have a particularized suspicion of wrongdoing.

That’s not to say the government shouldn’t have systems to alert authorities to crimes in the making. The Federal Bureau of Investigation, for example, has a set of “tripwires” designed to detect when someone is trying to build a powerful explosive. The system, which is integrated into the supply chain for materials that can be used to make a bomb, helped the feds discover and convict a Saudi man who was trying to cobble together a substance similar to TNT, the Wall Street Journal reported.

But it’s one thing to monitor the substances that can be used to make explosives, poisons or other weapons of mass destruction; it’s another thing entirely for authorities to pore through routinely collected data in search of something, anything, that looks suspicious.

And government isn’t the only force to reckon with. There’s also the potential that employers, insurers, litigants and other private parties will find ways to use data gathered routinely in public places to the detriment of the unsuspecting public. Even law-abiding people may need the ability to move through public places anonymously -- for example, to attend an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting or to see a divorce lawyer.

“I’m looking ahead in horror to the day when our security cameras are equipped with facial recognition biometrics,” said Beth Givens of the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse of San Diego. “When that day comes, there will be absolutely no anonymity in public places.”

It’s a great thing when a camera meant to stop shoplifters helps police identify suspects in a terrorist attack or other brutal crime. The presence of such cameras also makes at least some people feel safer because of their potential to deter crime. But there’s a trade-off between security on the one hand and privacy and liberty on the other. The more we try to shift from a system that helps investigate crimes to one that’s designed to prevent them, the more acute those trade-offs become.

ALSO:

Schwarzenegger: California’s silent disaster

Goldberg: Kermit Gosnell and abortion’s darkest side

Slide show: 10 reasons to salute L.A.’s promising transportation future

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.